It is degrading to miss the person who injured you. You might be wondering yourself, why do I miss them when they hurt me? That question can make one doubt himself, feel guilty, or even get angry at him/herself. But this is no more, or less, psychological an experience than it appears.

The fact that you miss a person who has hurt you does not mean that the harm was not real, neither does it imply that you are romanticizing the pain and forgetting what actually took place. Neither does it imply that you are yearning back to the pain. I mean by that that there is something more than logic responding, your nervous system, and emotional brain.

The emotional and physical brain makes a human being attached and not the rational mind. The fact that a relationship turns unhealthy does not make that system to switch off. It clings to familiarity, emotional investment, moments together and the significance you had previously attached to the individual. It happens that though your rational brain knows why this relationship was bad, your emotional brain is still mourning the loss.

Starting the healing process is as simple as ceasing to judge yourself in not missing them and realizing what you feel is attempting to process. The pull becomes less hard with time, safety, and self-compassion. What used to be confusing becomes clearat one does not miss the pain but is shedding an attachment that had a role to play, though it may have been toxic.

1. The Brain Bonds Before It Judges

1. Attachment Is About Connection, Not Fairness

Connection is what motivates human attachment, as opposed to the healthiness or equality of the relationship. The brain releases the chemicals such as dopamine and oxytocin when emotional intimacy is created among them through intimacy, vulnerability, or through a high frequency of interaction. These generate a sense of comfort, safety and familiarity of emotion. Gradually the brain becomes used to that individual as a relief and emotional crutch.

2. How Everyday Moments Build Attachment

Attachment grows in ordinary, repeated moments:

-

good morning messages

-

calls after work

-

evening tea

-

feeling understood in daily life

It is these trivial habits that condition the nervous to anticipate the appearance of someone. Brain is not logical, but pattern: emotional damage does not necessarily wipe out attachment.

3. Why Attachment Remains Even When It Becomes Painful

The emotional brain will grab what is familiar to it just as we grab our comfort food when we are under stress. You might wish to send them text messages when you feel overwhelmed, consider them even when you are just sitting and missing them the most during night-time- the time when the relationship used to be the most alive.

4. What You’re Really Missing

You are not missing how they hurt you. You are missing:

-

the emotional habit

-

their role in your daily rhythm

-

the sense of belonging your system learned

This is why longing can exist even after you understand the relationship was unhealthy.

5. What Longing Actually Means

Desire does not mean that the suffering was justified. It is an indication that your brain is untraining an attachment that you once depended on. Your nervous system develops new configurations with time and experience of constant safety. What seemed impossible to give was less and less hard, more natural and less difficult to hold on.

2. Intermittent Care Creates Stronger Attachment

1. Why They Don’t Look “Bad” All the Time

Most of the painful relationships are not harmful at any given time. Sometimes the individual listens, consoles you, or makes you feel very deeply understood. At other periods they draw back, condemn, overlook, or put you to the question of your value.

This back and forth does not bring clarity, it brings about emotional confusion.

2. Living According to Their Mood

Over time, the relationship begins to depend on their emotional state. You may find yourself thinking:

-

If I say the right thing today, maybe they’ll be kind again.

-

They were loving yesterday—maybe this time it will last.

Because the warmth is unpredictable, it feels especially powerful when it appears.

3. How the Brain Becomes Conditioned

Such inconsistency conditions the emotional brain to pay attention to the positive moments as opposed to doubting the bad. The nervous system does not inquire about the repeated occurrence of the pain, but awaits the next occurrence of love.

This benevolence is more precious, just due to the fact that it is not obligatory.

4. What You Actually Miss

Frequently it is not the relationship itself which you miss, but the potential which you retained. You mourn the incarnation of them that was responsive, kind and emotionally available, the one that manifested itself frequently enough to keep the hope alive.

Releasing will mean mourning over that hope and that may be more difficult than mourning the human.

5. Why This Is Not Your Fault

This insight minimizes self-blame. You were not “too attached.”

You were reacting to an order which conditioned your nervous system to gum through the thick and thin. The attachment was in fact conditioning.

3. Familiar Pain Feels Safer Than Unknown Peace

1. How Childhood Patterns Shape Safety

In case your childhood was marked by emotional inconsistency, neglect, or invalidation, your nervous system might have been conditioned to perceive this to be normal. You might have unconsciously thus taken in messages like:

-

love means waiting

-

It means adjusting yourself

-

love means staying quiet or earning attention

These early experiences shape what your body later recognizes as connection.

2. Why Healthy Love Can Feel Uncomfortable

This may manifest as intolerance in the adult life in the form of stable and consistent relationships. Reliable and calm, emotional, and available individuals will be dull, strange, and even unsafe.

Meanwhile, when relationships become emotionally turbulent you can experience it as intense, meaningful, or real not because it is a healthy relationship, but because it is the kind of relationship that your nervous system tells you it is.

3. The Lack of any Familiarity, not the Person.

A familiar pattern is lost with the end of a painful relationship as well as is the person. Even malicious familiarity may be secure as compared to the unfamiliar. This is the reason why you will miss a person who abused you more than a person who was good to you.

4. What You’re Really Learning

You might not miss them as they suited you. You might overlook them since your nervous system is yet to be taught a new meaning of safety. Healing does not have to do with pushing yourself to heal more quickly, but rather about learning to teach your system gradually that, with no anxiousness, self-abandonment, or fear, relationships can be calmed, respectful, and emotionally secure.

5. How Change Happens Over Time

Over time, there may be stability, familiarity and secure connection making what previously was foreign start to be secure. And that which was once, though hurtful, normal, may finally begin to slip.

4. You Miss the Version of Yourself You Were

1. Missing the Role You Played

Sometimes it is not the other person that you miss, it is the image of yourself that you were in the relationship.

You can afford not to have been the one who made the attempt and waited and appeared and did more than you got. It is painful, but that could have provided you with a sense of purpose, identity, or value, in emotion.

2. Missing the Intensity

You even might be deprived of that emotion life the relationship gave. Great emotional moods may render life significant, melodramatic, and vivid. Once such intensity has gone, the silence that remains may seem hollow or disturbing.

This is not that the relationship was healthy but rather it took up a high emotional space.

3. Why Letting Go is Like Losing Yourself.

Breaking-up the relationship may seem like losing a part of yourself, particularly when you had built your thoughts, habits, future plans, or sense of self around it. It is not merely a relational loss, but rather an existential loss. You are being challenged to recreate yourself minus the struggle, the story and the hope that used to make you what you were.

4. Grieving the Versions of You

People we do not only grieve, versions of ourselves:

- the hopeful self

- loyal self

- the self who had hoped he would finally be safe in love.

Healing is to respect those versions with compassion and then giving oneself a chance to become someone different someone who does not have to be hurt to experience reality and does not have to suffer to feel connected and significant.

5. Missing Is Not the Same as Wanting Them Back

1. Missing Is Not Proof the Relationship Was Healthy

Craving one’s presence does not imply that the relationship was safe and going back is the most appropriate choice. It is just that your emotional system is functioning in the manner in which it is programmed to- process loss.

2. Logic and the Nervous System Don’t Move Together

When a connection ends, the mind and body don’t immediately align with logic. Your nervous system is losing:

-

a relationship

-

a familiar habit

-

emotional stimulation

-

a known pattern of relating

Feelings of longing, sadness, or nostalgia are not signals to go back—they are signs that attachment is slowly unraveling.

3. Why Memories Appear Suddenly

Memories can be replicated in the ordinary activities of life, at night or when revived by something. Such times do not imply that you have not healed. They do not refer to your system as integrating the past, but avoiding it.

4. What Healing Actually Looks Like

Healing is not forgetting, blocking out, or minimizing what the relationship meant. Healing is:

-

remembering without being pulled back

-

holding the truth of what you felt and what you know

-

choosing distance with clarity, not denial

5. What Changes With Time

Over time, the ache softens. Memories lose their emotional charge. What once felt like a command to return becomes a passing thought. This is not weakness—it is growth.

6. Why Logic Alone Doesn’t Stop the Ache

1. Knowing and Longing Can Coexist

You may intellectually understand that the relationship was unhealthy and still long deeply for the person. This can feel confusing or discouraging, but it is a natural human response.

2. Two Parts of the Brain

The thinking brain holds logic, reasoning, and insight.

Attachment lives in the emotional and bodily brain, where memories are stored as feelings, sensations, and patterns.

3. Why the Body Reacts

Even when the mind understands, the body may respond with heaviness in the chest, restlessness, or sudden longing. These are not signs of going backward—they show the nervous system releasing an attachment that once felt necessary.

4. Healing Is More Than Understanding

Awareness explains the experience but doesn’t always calm the body. Healing happens through nervous system regulation, self-compassion without shame, and repeated experiences of safe, emotionally available relationships.

5. What Changes Over Time

With consistent safety, the emotional brain learns what the thinking brain already knows:

connection does not have to hurt to be real.

Longing softens because the system no longer needs it to feel secure.

7. What Helps When You Miss Someone Who Hurt You

-

Name the truth gently: “I miss the connection, not the harm.”

-

Allow the feeling without judgment: Missing is a feeling, not a decision.

-

Strengthen your present safety: Consistent routines, supportive people, grounding practices.

-

Grieve fully: Closure comes from processing, not suppressing.

-

Redefine love: Over time, emotional consistency will begin to feel more comforting than intensity.

A Closing Thought

You can talk it over mentally that the relationship was unhealthy, but you still long to have the person. This may be confusing or even demoralizing, but it is a very normal human reaction.

Logic, reasoning and insight are the functions of the thinking brain. This is the place where you realize, “This did not work out well with me.

Attachment, however, exists in the emotional and bodily brain where the memories are stored in the form of sensation, feeling and pattern of emotion.

And this is why your body might continue to need to respond with tightness in the chest, restlessness or a sudden rush to miss them. Such reactions do not indicate that you are going regressive. They indicate that it is a gradual release of an attachment that you once needed by your nervous system.

Knowledge does not work wonders. No sense has a way of making you know what you are going through but that does not necessarily soothe the body. The process of healing occurs by regulating the nervous system, with self-compassion devoid of shame, and by repetition in safe and consistent, emotionally available relationships.

Over time, the emotional brain learns what the thinking brain already knows:

connection does not have to hurt to be real.

FAQs — Why You Miss People Who Hurt You

1. Why should I miss someone who abused me?

You can lose the emotional connection, familiarity and the pattern of attachment and not the actual treatment. Our nervous system develops strong ties even in unfaithful or malicious relationships.

2. Does the fact that one misses another person imply that the relationship was good?

No — it does not mean that the relationship was healthy when one misses a person. It is possible to have emotional attachment and grief even when the experience was detrimental.

3. What is a trauma bond?

A trauma bond is a psychological attachment resulting when the abuse and new positive experiences are repeated in contact and your brain has learned to stand by the unpredictability.

4. Why can it be more difficult to let go of good ones?

Random acts of positivity bring intermittent positive reinforcement, which leaves a stronger impression of attachment than regular acts of kindness would.

5. Can it be normal to miss another person after leaving him?

Yes – – even when the relationship is finished the nervous system can be in withdrawal and desire familiarity.

6. Why is it that serene and emotional safety is so strange?

In case the early attachment was inconsistent or neglected, the emotional system might view stability as something foreign or uncomfortable.

7. Are there any such things as trauma bonds in friendship or simply in romantic relationships?

Trauma bonds are possible in any type of relationship, not only romantic relationships, when one person gets emotionally dependent despite abuse.

8. Are the absence of them that I desire them?

Not necessarily. You will not miss the pain or the presence of the other person, but the bond, comfort, hope and identity associated with the relationship.

9. Which theory of attachment (psychological) is applicable?

The John Bowlby theory of attachment demonstrates that human beings are designed to seek relationships to ensure their safety and survival in life, however, inconsistent, or painful.

10. What is so difficult about heartbreak, body-wise?

Separations cause emotional pain which results in brain activation of similar areas as those of physical pain- since loss of attachment is perceived by the nervous system as a threat.

11. Is it possible to be trauma bonded and not abused?

Trauma bonding is generally associated with harmful relationships, but neglect, inconsistency, or emotional volatility also can be unhealthy attachment.

12. What is the time taken to miss them?

No specific timeline exists, and the healing, regulation, new safe experience, and time are the factors that would help to restore equilibrium.

13. How is the difference between love and attachment?

Love within healthy relationships is not something to worry about, and attachment within harmful relationships is usually something to be addictive and uncertain.

14. Can therapy help with this?

Yes, therapy and treatment in particular, trauma-informed or attachment-based treatment could serve to unpack patterns and establish emotional safety.

15. Does it make one weak when he or she misses someone?

No — the feeling of missing someone who hurt you is not a moral weakness, it is a human emotional process. It is a part of the unraveling of old patterns in the brain with time.

Written by Baishakhi Das

Counselor | Mental Health Practitioner

B.Sc, M.Sc, PG Diploma in Counseling

Reference

-

Why You Miss the Person Who Hurt You — Medium article explaining emotional conditioning and trauma bonds. Read on Medium (Hello Love)

-

Loss and Attachment: How It Impacts Us — Ways of Blooming overview of attachment and separation. Explore Attachment and Loss

-

Trauma Bonding: What It Is — Healthline FAQ about trauma bonds. Trauma Bonding Explained (Healthline)

-

When Pain Feels Familiar — MIP Therapy on missing someone and healing. When Pain Feels Familiar

-

Attachment Bond Theory — Wikipedia overview of affectional bonds and attachment. Attachment Bond Theory (Wikipedia)

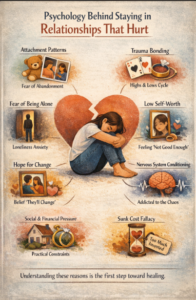

- Psychology Behind Staying in Relationships That Hurt

This topic performs well due to rising searches around men’s mental health, workplace stress, and burnout recovery. Combining emotional insight with practical steps increases engagement and trust.

1. The Brain Is Wired for Social Survival

1. The Brain Is Wired for Social Survival