A psychological perspective on stress, silence, and healing

Introduction

Burnout has become one of the most common—yet least openly discussed—mental health issues among working men. Across many societies, men are expected to be productive, resilient, and emotionally steady, regardless of workload, pressure, or inner strain. Admitting exhaustion or emotional distress is often interpreted as weakness, which pushes many men to keep functioning on the surface while struggling internally. As a result, burnout in men frequently goes unrecognized and untreated until it reaches a breaking point.

Unlike temporary stress, burnout is a chronic condition involving physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion caused by sustained pressure without adequate recovery, rest, or emotional support. It develops gradually, often unnoticed, as men continue to meet external expectations while ignoring internal warning signs. For working men, burnout is commonly hidden behind long work hours, irritability, emotional withdrawal, silence, or numbness—signals that are often normalized rather than recognized as distress. Over time, this hidden exhaustion erodes motivation, well-being, and mental health, making recovery more difficult the longer it remains unaddressed.

Why Working Men Are Especially Vulnerable to Burnout

Working men face a unique combination of psychological, social, and cultural pressures that significantly increase their risk of burnout. These pressures often discourage rest and emotional expression, allowing stress to accumulate silently over time.

Identity Tied to Work and Providing

For many men, self-worth is closely linked to productivity, income, and professional success. Being a provider is often seen as a core measure of value. When work becomes overwhelming or performance drops, it can trigger deep feelings of inadequacy—pushing men to work harder rather than pause.

Emotional Suppression

Men are frequently conditioned to endure stress quietly. Expressing vulnerability or emotional exhaustion is often discouraged, while endurance is praised. As a result, stress is internalized rather than processed, increasing psychological strain.

Limited Support Systems

Many adult men have fewer emotionally intimate friendships. Without safe outlets to talk openly, stress has little opportunity to be released, making burnout more likely.

Fear of Appearing Weak

Asking for help—whether emotional support, rest, or flexibility—can feel threatening to identity or social status. This fear keeps many men stuck in silence, even when they are struggling.

Over time, these factors cause stress to build internally rather than discharge, leading to burnout instead of relief.

Common Signs of Burnout in Working Men

Burnout in men does not always look like sadness, tears, or collapse. More often, it appears through subtle emotional, mental, physical, and behavioral changes that are easily mistaken for normal work stress.

1. Emotional Signs

- Emotional numbness or detachment

- Irritability, anger, or frequent frustration

- Loss of motivation or sense of purpose

- Feeling “empty” or disconnected despite achievements

2. Mental Signs

- Difficulty concentrating or making decisions

- Cynicism or negativity toward work or life

- Constant mental fatigue or brain fog

- Feeling trapped, stuck, or helpless

3. Physical Signs

- Persistent tiredness even after rest

- Headaches, body pain, or digestive problems

- Sleep disturbances or unrefreshing sleep

- Frequent illness due to weakened immunity

4. Behavioral Signs

- Overworking or inability to disconnect from work

- Withdrawal from family, friends, or activities

- Increased use of alcohol, nicotine, or other substances

- Procrastination, mistakes, or declining performance

Many men misinterpret these signs as “normal stress” and continue pushing themselves harder. Unfortunately, this response deepens exhaustion and accelerates burnout rather than resolving it.

Key Insight

Burnout is not a failure of resilience—it is a warning signal that emotional and physical limits have been exceeded. Recognizing these signs early is the first step toward recovery.

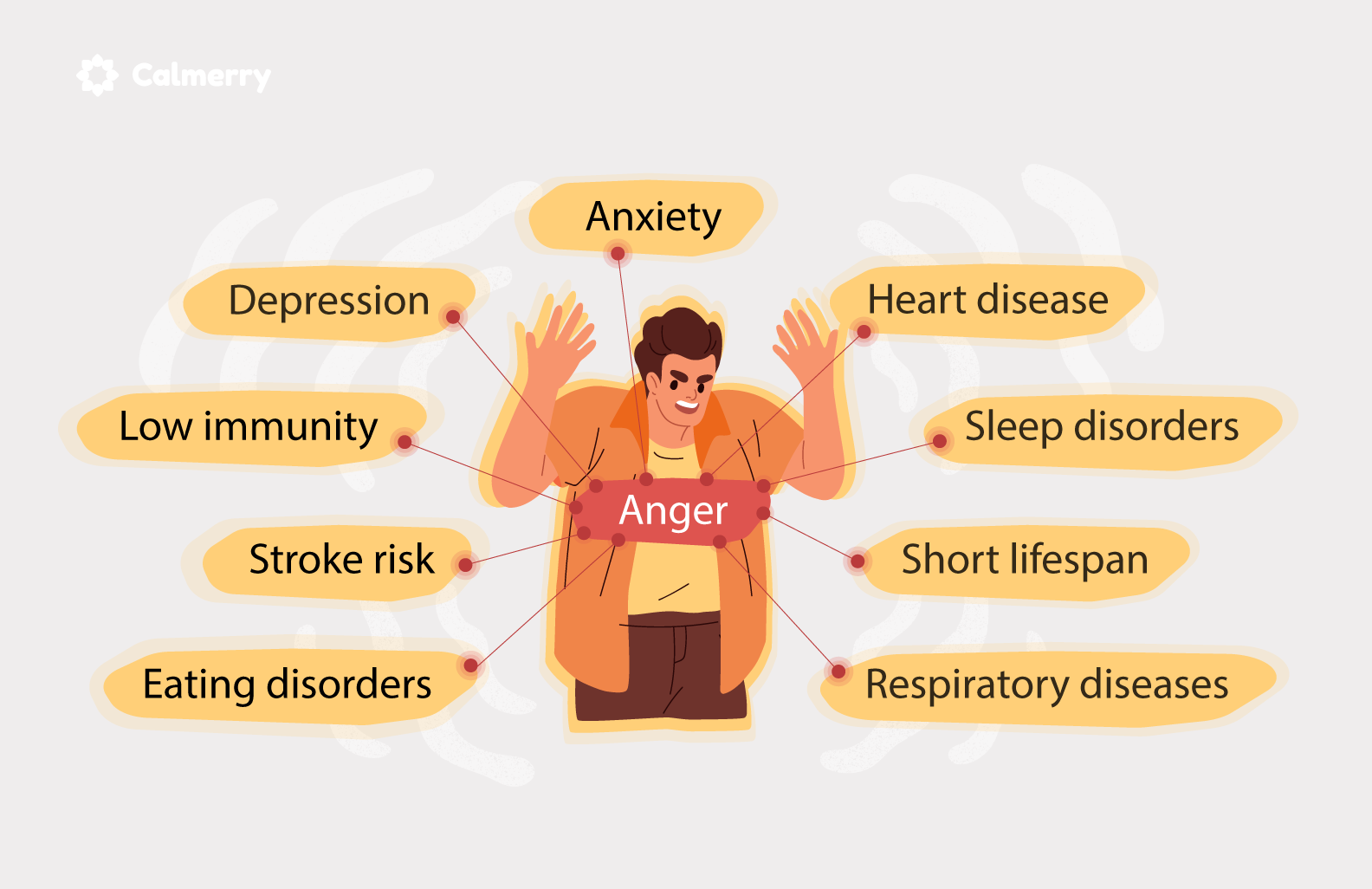

Psychological Impact of Untreated Burnout

When burnout is ignored or normalized, its effects extend far beyond feeling tired or stressed. Untreated burnout gradually erodes mental health, emotional stability, and identity, especially in working men who continue functioning without support.

If left unaddressed, burnout can lead to:

-

Depression and anxiety

Persistent exhaustion and hopelessness can evolve into clinical depression or chronic anxiety, often masked by irritability or emotional withdrawal. -

Emotional shutdown and relationship conflicts

Burned-out men may detach emotionally as a form of self-protection, leading to misunderstandings, distance, and frequent conflict in close relationships. -

Increased risk of substance dependence

Alcohol, nicotine, or other substances may be used to numb emotional pain or manage stress, creating harmful coping cycles. -

Loss of self-esteem and identity confusion

When productivity declines, men who tie identity to work may feel worthless, lost, or disconnected from their sense of self. -

Higher risk of suicidal thoughts

Prolonged emotional exhaustion combined with isolation can increase feelings of hopelessness and despair.

It is crucial to understand that burnout is not a lack of resilience or strength. It is a psychological signal that coping capacity has been exceeded for too long without adequate recovery or emotional support. Recognizing burnout early is not weakness—it is an essential step toward healing and long-term mental well-being.

Why Men Struggle to Acknowledge Burnout

Many men delay recognizing or admitting burnout because of deeply ingrained beliefs and external expectations that discourage rest and emotional honesty.

-

Rest is often equated with laziness, making breaks feel undeserved rather than necessary.

-

Fear of disappointing family, employers, or dependents pushes men to keep going even when exhausted.

-

Comparing their struggles to others leads many men to minimize their own distress—believing someone else “has it worse.”

-

Endurance is consistently rewarded, while self-care is rarely acknowledged or encouraged.

Over time, silence becomes a coping mechanism—a way to maintain responsibility and identity. However, this silence does not protect mental health. Instead, it deepens exhaustion, isolates emotional pain, and accelerates burnout, making recovery harder the longer it is postponed.

Recovering from burnout is not just about taking time off work. While rest is important, real recovery requires psychological, emotional, and lifestyle changes that address the root causes of exhaustion—not just its symptoms.

1. Recognizing Burnout Without Shame

The first and most critical step is acknowledging burnout as a health condition, not a personal failure. Burnout develops when demands exceed coping capacity for too long—not because someone is weak or incapable.

Naming the problem:

- Reduces self-blame

- Lowers internal pressure

- Creates space for reflection and healing

Awareness itself is a powerful beginning.

2. Redefining Productivity and Masculinity

Recovery often requires challenging deeply ingrained beliefs such as:

- “My worth equals my output”

- “I must always be strong”

- “Rest means weakness”

These beliefs keep men trapped in over functioning. Healthy masculinity includes self-awareness, boundaries, and emotional honesty. Productivity should support life—not replace it.

3. Restoring Emotional Expression

Burnout thrives where emotions are suppressed. Men benefit from learning to:

- Identify emotions beyond anger or stress

- Talk about pressure without minimizing it

- Express needs clearly, calmly, and without guilt

Emotional expression allows stress to be processed instead of stored, reducing internal overload and emotional numbness.

4. Rebuilding Boundaries at Work

Burnout improves when men regain a sense of control over time and energy. Practical steps include:

- Limiting work hours where possible

- Scheduling non-negotiable rest

- Reducing constant availability (emails, calls)

- Taking breaks without guilt

Boundaries are not laziness—they are protective mental health tools.

5. Strengthening Support Systems

Burnout recovers faster in the presence of connection. Helpful supports include:

- Trusted conversations with friends or family

- Peer support groups

- Mentors who model balance and self-respect

- Therapy or counseling

Connection reduces isolation and reminds men they are not carrying everything alone. Social support is one of the strongest buffers against burnout.

6. Therapy as a Recovery Tool

Therapy provides a structured space for working men to:

- Understand personal burnout patterns

- Address perfectionism and chronic pressure

- Heal emotional suppression

- Develop sustainable coping strategies

- Seeking therapy is not weakness—it is preventive mental healthcare and an investment in long-term well-being.

Preventing Burnout in the Long Term

Burnout prevention is an ongoing process, not a one-time fix. It involves:

- Regular emotional check-ins

- Maintaining interests and identity outside work

- Building friendships not centered on productivity

- Prioritizing sleep, movement, and rest

- Allowing vulnerability without self-judgment

Burnout becomes less likely when life holds meaning beyond performance and when self-worth is not tied solely to output.

Conclusion

Burnout in working men is not a personal flaw—it is a systemic outcome of chronic pressure, emotional silence, and unrealistic expectations.

Men are not machines.

They are not meant to endure endlessly.

Rest is not quitting.

Asking for help is not weakness.

Recovery is responsibility.

When working men are allowed to slow down, speak up, and reconnect—with themselves and others—burnout loses its grip, and mental health finally has space to heal.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is burnout in working men?

Burnout in working men is a state of chronic physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion caused by prolonged work stress without sufficient rest or emotional support.

2. How is burnout different from normal stress?

Stress is usually temporary and situation-based, while burnout is long-term and leads to emotional numbness, reduced motivation, and mental exhaustion.

3. Why are men at higher risk of burnout?

Men often tie self-worth to productivity, suppress emotions, and hesitate to seek help, allowing stress to accumulate silently.

4. What are the early signs of burnout in men?

Early signs include irritability, emotional detachment, chronic fatigue, reduced concentration, and loss of motivation.

5. Can burnout affect relationships?

Yes. Burnout often leads to emotional withdrawal, poor communication, and increased conflict with partners and family members.

6. Is burnout linked to depression and anxiety?

Yes. Untreated burnout significantly increases the risk of depression, anxiety, substance use, and suicidal thoughts.

7. Why do men struggle to admit burnout?

Many men equate rest with laziness, fear disappointing others, and are socially rewarded for endurance rather than self-care.

8. Can taking leave alone cure burnout?

No. Leave helps temporarily, but full recovery requires emotional awareness, boundary setting, lifestyle changes, and support.

9. How does therapy help with burnout?

Therapy helps men understand stress patterns, challenge perfectionism, process emotions, and develop sustainable coping strategies.

10. Is seeking help a sign of weakness?

No. Seeking help is a sign of psychological maturity and preventive mental healthcare.

11. What role does emotional suppression play in burnout?

Suppressing emotions increases internal stress, leading to emotional numbness and faster burnout.

12. How can men prevent burnout long-term?

By maintaining work boundaries, nurturing relationships, prioritizing rest, and developing emotional literacy.

13. Does burnout only affect high-pressure jobs?

No. Burnout can occur in any job where effort is high and recovery or recognition is low.

14. Can burnout return after recovery?

Yes, if underlying patterns are not addressed. Sustainable changes reduce recurrence.

15. What is the most important step in burnout recovery?

Recognizing burnout without shame and seeking support early.

Written by Baishakhi Das

Counselor | Mental Health Practitioner

B.Sc, M.Sc, PG Diploma in Counseling

Reference

-

World Health Organization (WHO). Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”

https://www.who.int -

American Psychological Association (APA). Stress & Burnout

https://www.apa.org -

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the Burnout Experience.

World Psychiatry. -

Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (2009). Burnout: 35 years of research.

Career Development International. -

McLeod, S. A. (2023). Burnout. Simply Psychology

https://www.simplypsychology.org - Anger Issues in Men: What’s Really Going On

This topic performs well due to rising searches around men’s mental health, workplace stress, and burnout recovery. Combining emotional insight with practical steps increases engagement and trust.