Introduction

Attachment theory is a psychological framework developed by John Bowlby that explains the importance of the emotional bond between an infant and their primary caregiver for the child’s survival and healthy social-emotional development. It posits that infants instinctively seek to form attachments to caregivers who are consistently sensitive, responsive, and available, providing a secure base for exploration and a safe haven during distress or danger. This bond serves as the foundation for the child’s feelings of security and influences their emotional regulation and relationship patterns throughout life.

Attachment theory is subdivided into distinct attachment styles that describe patterns of bonding and behavior between children and their caregivers, as well as later in adult relationships. These subdivisions were originally identified in infancy but are also relevant across the lifespan.

Attachment theory, originally developed by John Bowlby and further expanded by Mary Ainsworth, provides a comprehensive framework for understanding how early relationships with caregivers shape emotional development and interpersonal relationships throughout life.

Core Concepts of Attachment Theory

Core concepts of attachment theory include Attachment Behavior, Secure Base and Safe Haven, and Internal Working Models. These concepts explain the emotional bond between infants and their caregivers and how this bond shapes lifelong social and emotional functioning.

Attachment Behavior

Attachment behaviors are innate actions infants use to maintain closeness to caregivers, especially in times of distress or danger. Examples include crying, clinging, reaching, smiling, and following. For instance, a baby crying loudly when left alone signals distress and prompts the caregiver to provide comfort and safety. These behaviors serve the biological purpose of ensuring the infant’s survival by keeping the caregiver close for protection and care.

Secure Base and Safe Haven

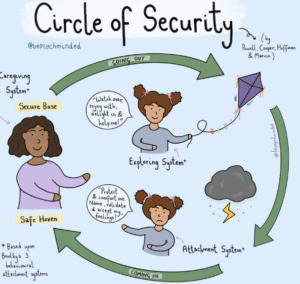

The caregiver provides a secure base, which allows the child to explore their environment confidently, knowing they can return to the caregiver if needed. At the same time, the caregiver acts as a safe haven—a source of comfort and reassurance during times of stress or fear. For example, a toddler playing in a park may explore freely but runs back to the parent when frightened by a loud noise, seeking reassurance and protection.

Internal Working Models

Early interactions with caregivers lead children to form internal working models—mental frameworks about the self and others in relationships. These models guide expectations and behavior in future relationships. For example, a child with sensitive, responsive caregivers may develop a model of themselves as worthy of love and others as reliable and trustworthy, fostering positive social interactions. Conversely, inconsistent caregiving may lead to models where the self is seen as unworthy and others as unpredictable, influencing anxiety and mistrust in relationships throughout life.

Attachment Phases (Bowlby’s Model)

Bowlby’s Attachment Theory describes four key phases of attachment development in children, each characterized by specific behaviors and emotional milestones, with examples illustrating how the infant and caregiver interact at each stage:

Pre-attachment Phase (0-6 weeks)

Infants show no preference for a specific caregiver but use innate signals such as crying, smiling, and grasping to attract attention from any adult.

Example: A newborn baby cries and smiles to anyone who responds, and does not show distress if picked up by a stranger, signaling indiscriminate social responsiveness.

Attachment-in-the-making (6 weeks to 6-8 months)

Infants begin to show a preference for familiar caregivers over strangers and start to recognize the caregiver’s voice and face.

Example: A 4-month-old may calm more quickly when soothed by their mother than by a stranger and shows more frequent smiles directed at the caregiver, indicating growing trust but still accepts care from others.

Clear-cut Attachment (6-8 months to 18-24 months)

Strong attachment behaviors emerge: infants clearly prefer their primary caregiver, show distress on separation (separation anxiety), and display wariness of strangers.

Example: A 10-month-old may cry intensely when the mother leaves the room and runs to her upon return, using her as a secure base for exploration while also showing stranger anxiety.

Goal-corrected Partnership (from 18-24 months onwards)

Children develop cognitive understanding of the caregiver’s needs and plans and can adjust their behavior accordingly. They negotiate closeness with more flexibility and consider the caregiver’s perspective.

Example: A 3-year-old understands that the caregiver may not always be immediately available; they might express their needs verbally and wait patiently for the caregiver to respond, such as waiting for a snack rather than demanding it immediately.

These phases reflect an evolving attachment system that helps ensure the child’s safety while fostering independence and emotional regulation. The process is foundational for secure emotional bonds and social development throughout life.

Detailed Breakdown of Attachment Styles

Attachment styles in children reflect distinct patterns of emotional bonding and responses to caregivers, which deeply impact their development and relationships.

- Secure Attachment: Children with secure attachment have caregivers who are consistently responsive and sensitive to their needs. These children feel confident about their worth and trust others. They seek comfort when distressed but also freely explore their environment, using the caregiver as a “secure base.”

Example: A securely attached toddler happily plays with toys but looks back to their parent regularly. If distressed, they seek the parent’s comfort and are easily soothed, then return to play with renewed confidence. - Anxious-Ambivalent Attachment :This style arises from inconsistent caregiving, where caregivers are sometimes available and sometimes neglectful or unresponsive. Children become clingy, overly dependent, and fearful of abandonment. They have difficulty calming down and may display heightened distress when separated.

Example: An anxiously attached child may become extremely upset when a parent leaves and struggle to be comforted upon the parent’s return, often showing clinginess and needing constant reassurance. - Avoidant Attachment: Children with avoidant attachment experience caregivers who are emotionally unavailable, rejecting, or unresponsive. These children suppress their attachment needs, seeming emotionally distant or indifferent. They avoid seeking comfort or showing vulnerability.

Example: An avoidant child may not seek their caregiver when upset, may appear self-reliant, and avoid emotional closeness, even when frightened or hurt. - Disorganized Attachment: Disorganized attachment often stems from trauma, neglect, or frightening caregiving. Children display contradictory and confused behaviors, such as approaching the caregiver while also showing fear or avoidance. Their behavior signals emotional conflict and confusion.

Example: A child might freeze or show fear when the caregiver approaches or display both clinginess and withdrawal simultaneously, reflecting their conflicted feelings toward the caregiver.

These attachment styles significantly influence children’s emotional regulation, social development, and future relationship patterns. Understanding these examples helps caregivers and professionals provide appropriate support to foster secure, healthy attachments.

Attachment in Adults

These adult attachment styles influence how individuals approach relationships, handle conflict, and regulate emotions, often reflecting the internal working models developed in early childhood. Recognizing one’s attachment style can be empowering for personal growth and improving relationship dynamics.

Importance and Applications

Attachment theory plays a crucial role in several fields by providing practical tools and insights to enhance emotional wellbeing and interpersonal relationships, with real-world examples illustrating its impact:

Psychotherapy

Attachment theory informs therapeutic approaches by helping clinicians understand clients’ relational patterns and emotional regulation difficulties rooted in early attachment experiences. For example, therapists use attachment-based therapy to help clients with anxiety or trauma explore and heal early attachment wounds, fostering more secure relational dynamics. Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) for couples is a direct application, where partners learn to recognize attachment needs, respond sensitively, and rebuild trust, significantly improving relationship quality.

Parenting

Attachment theory guides parents toward responsive and sensitive caregiving that promotes secure attachment and healthy child development. Parenting programs often include psychoeducation and video feedback to help parents recognize their child’s signals and respond appropriately. For instance, a parent who learns to soothe a crying baby consistently helps the infant develop trust and emotional security, strengthening the parent-child bond and fostering the child’s resilience.

Education

Teachers applying attachment principles create supportive classroom environments where students feel safe to explore and learn. Programs like My Teaching Partner (MTP) train educators to act as a “secure base,” enhancing student engagement, emotional regulation, and academic success.

Healthcare and Social Care

Attachment-informed practices improve caregiving in hospitals, foster care, and social services by emphasizing consistent, nurturing relationships. For example, reducing caregiver turnover and promoting stable placements for children in foster care improves attachment security, leading to better mental health outcomes.

Relationships

Attachment awareness helps individuals understand their own and others’ relational behaviors. Couples can better navigate conflicts by recognizing attachment triggers and responding with empathy rather than defensiveness, fostering healthier, more secure partnerships.

Public Health and Policy

Attachment research has influenced child welfare policies by highlighting the importance of stable and sensitive caregiving for healthy development. Studies like Rene Spitz’s on hospitalism catalyzed reforms towards family-centered care in institutional settings, reducing childhood mortality and developmental delays.

In summary, attachment theory’s practical applications permeate psychotherapy, parenting, education, healthcare, relationships, and public policy, providing a universal framework to promote secure attachments and enhance emotional and social wellbeing throughout life.

Developmental Psychology

Attachment theory provides insights into emotional and social development milestones, highlighting how early attachment influences later mental health, social competence, and stress regulation. It informs research and interventions focused on promoting security and addressing vulnerabilities in childhood to foster lifelong wellbeing.

Overall, attachment theory is foundational in understanding human development and functioning, shaping clinical practice, parenting, and building stronger, more supportive relationships across the lifespan.

Conclusion

Attachment theory, pioneered by John Bowlby and expanded by Mary Ainsworth, emphasizes the crucial role early emotional bonds between infants and caregivers play in shaping social, emotional, and cognitive development throughout life.

The core concepts—attachment behaviors, secure base and safe haven, and internal working models—illustrate how infants instinctively seek proximity to sensitive and responsive caregivers for survival and emotional security. Bowlby’s attachment phases describe the evolving nature of this bond from birth through toddlerhood, highlighting the growing complexity of attachment behaviors and mutual understanding between child and caregiver.

Attachment styles—secure, anxious-ambivalent, avoidant, and disorganized—reflect patterns of caregiver responsiveness and shape the child’s expectations and strategies for managing relationships. These early attachments extend into adulthood, influencing romantic relationships and interpersonal dynamics, where secure attachment supports healthy intimacy while insecure styles may lead to difficulties in trust and emotional regulation.

The theory’s importance spans psychotherapy, parenting, relationships, and developmental psychology. Therapists use attachment insights to customize interventions that address relational issues and emotional trauma. Parenting guided by attachment principles promotes sensitive caregiving that fosters resilience and emotional well-being. Understanding attachment helps explain human behavior in relationships and guides efforts to support social and emotional development across the lifespan.

In conclusion, attachment theory provides a comprehensive framework to understand how foundational early relationships critically influence lifelong emotional health, social competence, and interpersonal fulfillment. It remains a cornerstone of psychological theory and practice, enriching clinical approaches, parenting, and research on human development.

References

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss.

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1978). Patterns of Attachment.

“Attachment Theory: Bowlby and Ainsworth’s Theory Explained,” Verywell Mind.

“Attachment Theory,” Simply Psychology, 2025.

“Attachment Styles in Adult Relationships,” Attachment Project, 2025.

“Practitioner Review: Clinical applications of attachment theory,” PMC, 2011.

Positive Psychology, 2025, “Attachment Theory, Bowlby’s Stages & Attachment Styles.”

“Attachment theory,” Wikipedia, 2004