Introduction

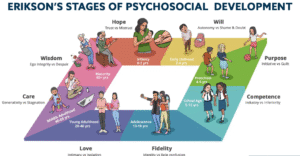

Erikson’s psychosocial development model outlines eight distinct stages, each characterized by a central conflict or crisis that must be resolved for healthy psychological growth. These crises, if navigated successfully, lead to the development of core virtues or strengths that serve as a foundation for future challenges and life transitions. Unlike Freud’s focus on innate drives, Erikson underscored the importance of social interactions and experiences during key periods of life, from infancy to old age.

Significance of the Theory

This lifespan approach highlights that personality development is an ongoing process, and that unresolved conflicts at any stage can influence later life outcomes. It emphasizes that social and cultural context, along with individual efforts, play crucial roles in shaping self-image, competence, and resilience. Overall, Erikson’s theory remains influential in clinical psychology, education, and social work, offering insights into how people face and adapt to various developmental challenges.

The Eight Stages Explained

- Trust vs. Mistrust (Infancy, 0-1.5 years):

The first stage of Erikson’s theory, Trust vs. Mistrust, occurs from birth to about 18 months. Infants depend entirely on caregivers for food, comfort, and safety. When caregivers consistently meet these needs, infants develop trust and a sense of security, leading to the virtue of hope. For example, a baby whose cries are promptly responded to learns the world is safe. Conversely, neglect or inconsistent care leads to mistrust, anxiety, and fear, as the baby feels uncertain and insecure about others’ reliability. This stage forms the emotional foundation for future relationships and confidence in the world.

- Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt (Early Childhood, 1-3 years):

The stage of Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt (ages 1-3 years) is when toddlers strive to do things by themselves, like dressing or toilet training. When caregivers encourage and support their efforts, children develop a sense of independence and confidence, which Erikson called “will.” For example, a toddler allowed to feed themselves, even if messy, feels capable. However, harsh criticism or control makes them doubt their abilities, leading to shame and low self-esteem. This stage is key to building a child’s self-confidence and willingness to try new things.

- Initiative vs. Guilt (Preschool, 3-6 years):

In Erikson’s third stage, Initiative vs. Guilt (ages 3-6), children start taking charge by initiating activities and asserting control, such as leading play or making decisions. When caregivers encourage these efforts, children develop a sense of purpose and confidence. For example, a child who plans and organizes a game feels proud and motivated. However, if caregivers criticize or discourage these initiatives, the child may develop guilt, feeling hesitant to try new things. Successfully balancing initiative and guilt helps children build ambition and resilience for future challenges.

- Industry vs. Inferiority (School Age, 5-12 years):

In Erikson’s stage of Industry vs. Inferiority (ages 6-12), children focus on developing skills and comparing themselves with peers, especially in school. When they receive recognition and encouragement for their efforts, they build competence and confidence. For example, a child praised for good work in a school project feels capable and motivated. However, repeated failure or ridicule can lead to feelings of inferiority and low self-esteem. This stage is crucial for developing a strong sense of competence and a positive self-image.

- Identity vs. Role Confusion (Adolescence, 12-18 years):

During adolescence (ages 12-18), Erikson’s stage of Identity vs. Role Confusion is when teenagers explore their values, beliefs, and life goals to form a clear sense of self. When supported in this exploration, they develop fidelity—the ability to stay true to themselves and others. For example, a teenager trying different hobbies, social groups, or career ideas with encouragement gains confidence in their identity. If teens face pressure, lack opportunity, or feel confused, they may experience role confusion, leading to uncertainty about their future and difficulty committing to an identity. This confusion can cause insecurity, isolation, or rebellion. Successfully resolving this stage builds a strong identity foundation for adulthood.

- Intimacy vs. Isolation (Young Adulthood, 18-40 years):

Erikson’s stage of Intimacy vs. Isolation (ages 18-40) involves adults seeking deep, meaningful connections and intimate relationships. Success in this stage results in the ability to form loving, trusting bonds with partners and close friends. For example, a young adult who openly shares feelings and supports their partner develops love and emotional closeness. Failure to establish such connections leads to loneliness and isolation, which may cause emotional pain and social withdrawal. This stage is crucial for building lifelong relationships and emotional well-being.

- Generativity vs. Stagnation (Middle Adulthood, 40-65 years):

In Erikson’s stage of Generativity vs. Stagnation (middle adulthood, ages 40-65), the focus shifts to contributing to society through work, family, and community involvement. People who successfully engage in activities like parenting, mentoring, or meaningful work develop a sense of purpose and care for future generations. For example, an adult actively mentoring younger colleagues or raising a family experiences fulfillment. Conversely, those who feel disconnected or unproductive may experience stagnation, characterized by a lack of growth, involvement, and fulfillment. This stage is vital for leaving a positive legacy and maintaining psychological well-being.

- Integrity vs. Despair (Late Adulthood, 65+ years):

In Erikson’s final stage, Integrity vs. Despair (late adulthood, 65+ years), older adults reflect on their lives and evaluate them as either meaningful and fulfilling or full of regrets. When they feel a sense of completeness, acceptance, and pride in their accomplishments, they develop integrity and wisdom, enabling them to face the end of life with peace. For example, an elder who feels satisfied with their life and relationships embraces this wisdom. Conversely, those who focus on missed opportunities or unresolved conflicts may experience despair, bitterness, and fear about death. This stage is crucial for achieving emotional well-being in later life.

Key Concepts

Erikson’s psychosocial theory incorporates several key concepts that provide depth to understanding human development:

Ego Identity

Ego identity is a central concept, referring to the conscious sense of self that emerges from successfully resolving the conflicts or crises at each stage of development. It is the integrated self-image that includes one’s values, beliefs, and goals, enabling effective interaction with society. For example, a teenager who navigates the Identity vs. Role Confusion stage by exploring career options and personal values forms a strong ego identity, leading to confidence in decision-making and social engagement later in life.

Virtues

Each stage of Erikson’s model presents a psychosocial crisis whose resolution grants a specific psychological strength or virtue. These virtues are essential for healthy development and provide the emotional tools needed for future challenges. Examples include:

- Hope in the Trust vs. Mistrust stage, which fosters optimism and trust in others.

- Will in Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt, encouraging self-control and independence.

- Purpose in Initiative vs. Guilt, supporting goal-directed behavior and leadership.

These virtues accumulate across stages, shaping a resilient personality capable of adapting to life’s ups and downs.

Epigenetic Principle

The epigenetic principle states that development unfolds in a predetermined, sequential order—each stage building on the outcomes of preceding ones. However, individual experiences and cultural influences impact how successfully each crisis is resolved. For example, a child raised in a supportive culture might resolve early stages like Trust vs. Mistrust more positively, creating a stronger foundation for later stages. Conversely, adverse experiences might delay or complicate resolution, affecting personality growth. This principle highlights the dynamic interaction between biological maturation and social context throughout life.

Integration and Example

A practical illustration is a young adult facing the Intimacy vs. Isolation stage. If they have formed a strong ego identity (from prior successful stages), embody virtues like love and will, and have been shaped by supportive experiences, they are more likely to form meaningful relationships. Conversely, unresolved crises or weak virtues may lead to isolation or loneliness.

In summary, Erikson’s key concepts—ego identity, virtues, and the epigenetic principle—explain how personality develops in a structured yet flexible way, shaped by both inherent sequencing and life experiences.

Application

Erikson’s theory is widely used in psychology and social work for understanding how individuals manage life’s challenges and transitions. It aids therapists, educators, and caregivers in identifying developmental strengths and areas of support.

| Stage | Age Range | Crisis | Virtue |

| Trust vs. Mistrust | 0-1.5 yrs | Reliable care vs. neglect | Hope |

| Autonomy vs. Shame | 1-3 yrs | Independence vs. excessive control | Will |

| Initiative vs. Guilt | 3-6 yrs | Initiative vs. disapproval | Purpose |

| Industry vs. Inferiority | 5-12 yrs | Competence vs. repeated failure | Competence |

| Identity vs. Role Confusion | 12-18 yrs | Exploration vs. confusion | Fidelity |

| Intimacy vs. Isolation | 18-40 yrs | Relationships vs. loneliness | Love |

| Generativity vs. Stagnation | 40-65 yrs | Contribution vs. lack of growth | Care |

| Integrity vs. Despair | 65+ yrs | Acceptance vs. regret | Wisdom |

Erikson’s psychosocial theory remains a foundational framework for understanding human growth, emotional health, and personal fulfillment throughout life

Conclusion

Erikson’s psychosocial theory provides a profound framework for understanding human development as a lifelong process shaped by social interactions and cultural context. By navigating eight critical stages—from trust building in infancy to reflecting on life in old age—individuals cultivate essential virtues that form a resilient and coherent ego identity. The theory’s key concepts, including ego identity, virtues, and the epigenetic principle, highlight the dynamic interplay between biological maturation and personal experiences, influencing personality and social functioning throughout life. This comprehensive model remains foundational in psychology, guiding research, therapeutic practices, and education focused on human growth and well-being.