Habits shape a large part of human behavior. From brushing teeth automatically in the morning to checking the phone without conscious thought, much of daily life is guided by habitual actions. These behaviors occur with minimal awareness because the brain learns to conserve mental energy by turning repeated actions into automatic patterns. Once established, habits run in the background, allowing individuals to focus attention on new or complex tasks.

Psychology explains habit formation not as a simple issue of willpower or self-control, but as a learning process shaped by experience, reinforcement, emotional outcomes, and repetition over time. Behaviors become habitual when they consistently serve a purpose—such as providing pleasure, reducing discomfort, or helping a person adapt to their environment. The brain learns what “works” and repeats it, often without conscious evaluation.

Learning theories—especially classical conditioning, operant conditioning, and social learning theory—offer a structured framework for understanding how habits are formed, maintained, and changed. These theories explain how environmental cues trigger behavior, how consequences strengthen or weaken actions, and how observation of others influences everyday routines. Together, they show that habits are not random or irrational; they are learned responses shaped by past interactions with the world.

This article explains habit formation step by step through the lens of learning theory, integrating core psychological principles with real-life examples. By understanding how habits develop at a psychological level, individuals and professionals can better identify why certain behaviors persist and how meaningful, sustainable change becomes possible.

What Is a Habit in Psychology?

In psychology, a habit is defined as a learned behavior that becomes automatic through repeated performance in a stable and predictable context. Once a habit is formed, the behavior is triggered with minimal conscious awareness or deliberate decision-making. This is why people often find themselves engaging in habitual actions—such as scrolling through their phone or snacking—without actively choosing to do so.

Unlike goal-directed actions, habits do not require ongoing motivation or effort. Instead, they are guided by learned associations between cues, behaviors, and outcomes. Over time, the brain prioritizes efficiency, allowing habitual behaviors to run automatically while conserving cognitive resources for new or demanding tasks.

Psychologically, habits involve several key components:

- Repetition – behaviors must be performed repeatedly for habits to form

- Environmental cues – specific situations, times, places, or emotional states trigger the behavior

- Reinforcement – rewards or relief that strengthen the behavior

- Reduced conscious effort over time – actions become faster, easier, and more automatic

From a learning theory perspective, habits are learned responses that persist because they have been consistently rewarded or paired with particular stimuli. Even habits that appear irrational often continue because they serve a psychological function, such as reducing stress, providing comfort, or creating a sense of predictability.

Learning Theory: The Foundation of Habit Formation

Learning theory explains human behavior as something acquired and shaped through continuous interaction with the environment. Rather than viewing behavior as fixed or purely driven by personality, learning theories emphasize experience, consequences, and observation as central mechanisms of change.

Several influential psychologists laid the foundation for understanding habit formation through learning:

- Ivan Pavlov – explained how habits can form through classical conditioning, where neutral cues become linked to automatic responses

- B.F. Skinner – demonstrated how habits are strengthened or weakened through operant conditioning, based on reinforcement and punishment

- Albert Bandura – showed that habits can also be learned through observation and imitation, even without direct reinforcement

Each of these theories highlights a different pathway through which habits develop—association, consequence, and modeling. Together, they provide a comprehensive explanation of why habits form, why they persist, and why changing them requires more than simple intention or willpower.

Classical Conditioning and Habit Formation

Core Idea

Classical conditioning explains how neutral stimuli become linked with automatic emotional or physiological responses through repeated pairing. Over time, the brain learns to respond to a previously neutral cue as if it naturally carries meaning. This learning happens without conscious intention, which is why classically conditioned habits often feel involuntary.

In habit formation, classical conditioning mainly explains how cues gain power—how certain sounds, places, times, or situations automatically trigger urges, emotions, or bodily reactions.

How It Works

The process unfolds in a predictable sequence:

- Neutral stimulus

A stimulus that initially has no special meaning

(e.g., a phone notification sound) - Naturally meaningful stimulus

Something that automatically produces a response

(e.g., receiving a message → pleasure, connection, validation) - Repeated pairing

The neutral stimulus and meaningful stimulus occur together many times - Conditioned response

Eventually, the neutral stimulus alone triggers the response

(the notification sound creates an urge to check the phone)

This mechanism was first demonstrated by Ivan Pavlov, who showed that dogs could learn to salivate to the sound of a bell after it was repeatedly paired with food. The bell itself had no biological meaning at first, but learning transformed it into a powerful trigger.

Habit Examples in Daily Life

Classical conditioning explains many everyday habits that are driven by cues rather than conscious choice:

- Feeling hungry when watching TV at night

The TV becomes associated with eating over time, triggering appetite even without physical hunger. - Feeling anxious when entering an exam hall

The environment becomes linked with past stress, activating anxiety automatically. - Craving tea or coffee at a fixed time daily

Time of day acts as a conditioned cue for alertness or comfort. - Reaching for the phone when hearing a notification sound

The sound alone triggers anticipation and urge.

In all these cases, environmental cues activate automatic responses, forming the foundation of many habits before any behavior even begins.

Why Classical Conditioning Matters for Habits

Classical conditioning explains why habits often feel emotionally driven and difficult to control. The response occurs first—urge, craving, anxiety—and behavior follows afterward. This means that habit change is not only about stopping behavior, but also about understanding and modifying the cues and emotional associations that trigger it.

From a learning theory perspective, classical conditioning creates the emotional and physiological groundwork upon which habits are later reinforced and maintained.

Operant Conditioning: The Core of Habit Maintenance

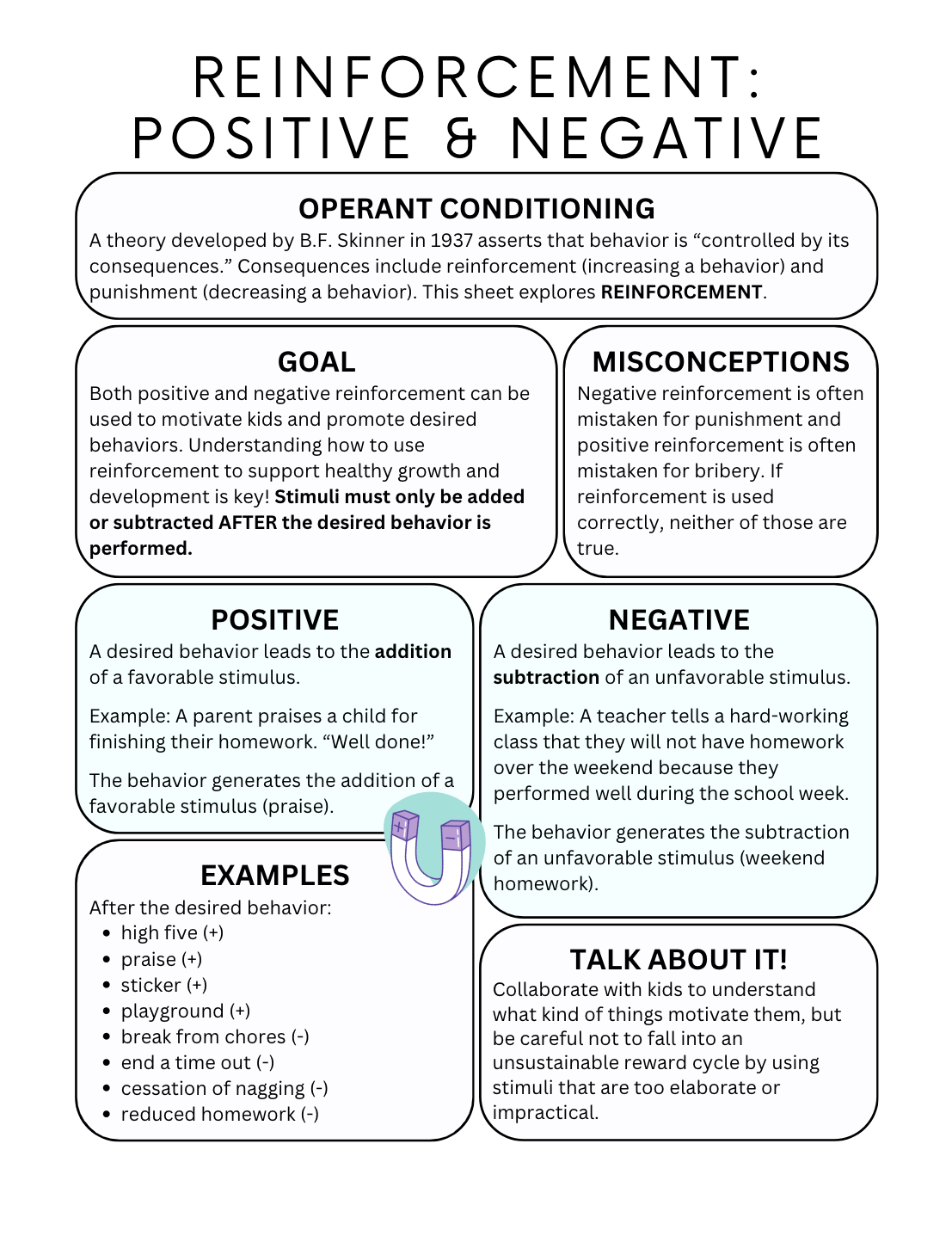

Reinforcement and Habits

Reinforcement is the central mechanism through which habits are strengthened and maintained. According to learning theory, behaviors do not become habits simply because they are repeated—they become habits because they are followed by outcomes the brain finds useful. These outcomes teach the brain which behaviors are worth repeating.

Positive Reinforcement

Positive reinforcement occurs when a behavior increases because it leads to a rewarding or pleasant outcome. The reward does not have to be large; even small emotional or psychological benefits are enough to strengthen behavior over time.

Examples:

- Checking social media → likes or comments → pleasure, validation

- Exercising regularly → praise, compliments, or improved body image

- Studying consistently → good grades, approval, or a sense of achievement

In each case, the brain learns:

“This behavior leads to something good—repeat it.”

Positive reinforcement is especially powerful when rewards are immediate, which is why many modern habits form quickly.

Negative Reinforcement

Negative reinforcement occurs when a behavior increases because it removes or reduces discomfort. Importantly, this is not punishment—it is relief-based learning.

Examples:

- Smoking → reduces anxiety or tension

- Procrastinating → temporary relief from academic or work stress

- Avoiding conflict → reduction in immediate emotional discomfort

Many unhealthy habits are maintained through negative reinforcement. Even when the long-term consequences are harmful, the short-term relief teaches the brain that the behavior is effective.

This explains why people often say:

“I know it’s bad for me, but it helps in the moment.”

From a learning theory perspective, that momentary relief is enough to reinforce the habit.

Why Habits Become Automatic

With repeated reinforcement, habits gradually shift from conscious choice to automatic response.

Over time:

- The brain learns which behaviors reliably bring reward or relief

- Conscious decision-making effort decreases

- The behavior becomes the default reaction in that situation

Neurologically, repeated reinforcement strengthens pathways in the basal ganglia, the brain region involved in automatic behavior and routine learning. Once this system is engaged, habits can run on “autopilot,” often without conscious awareness.

This is why people may say:

“I didn’t even realize I was doing it.”

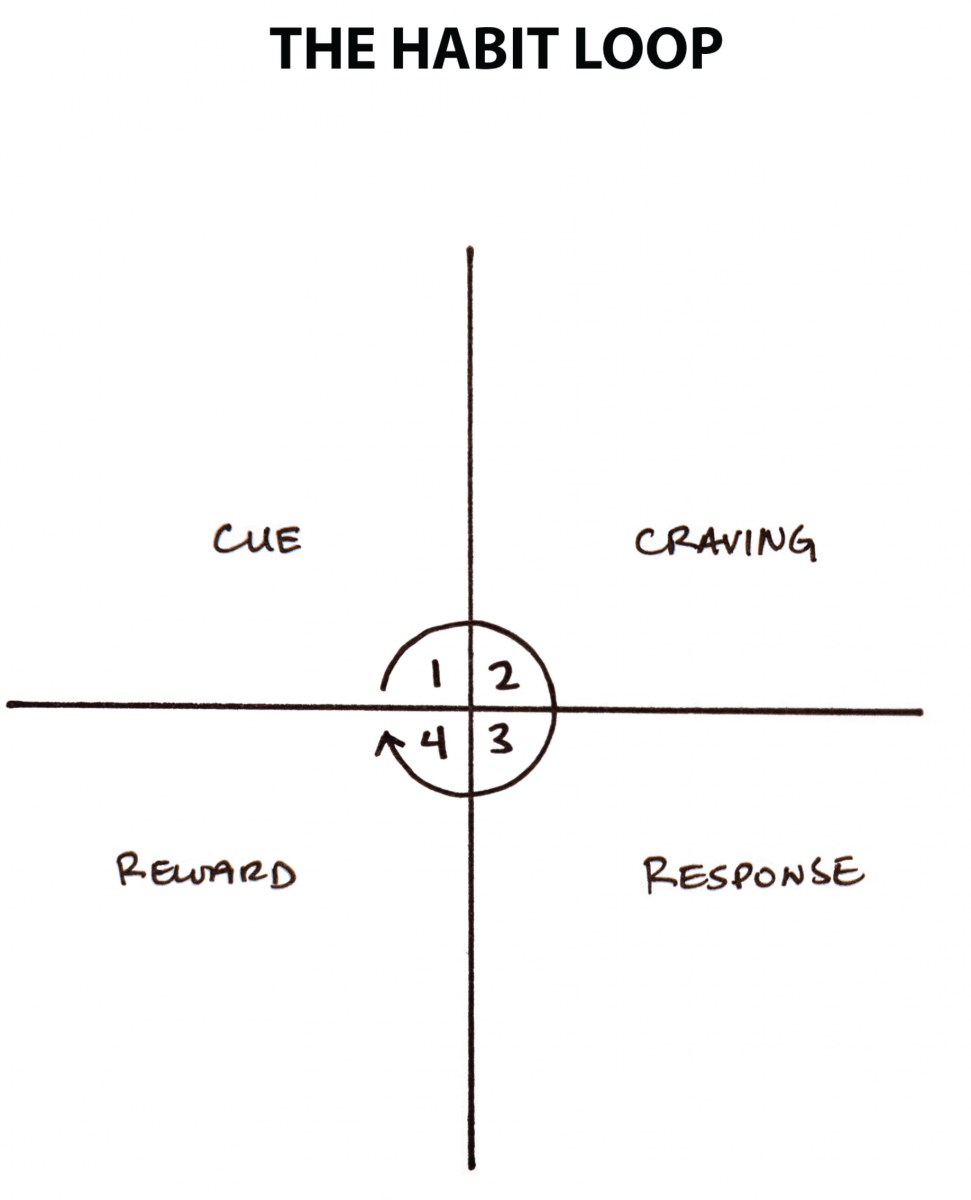

The Habit Loop Explained Through Learning Theory

A widely used framework that aligns closely with learning theory is the habit loop, which describes how habits are structured and maintained.

The loop consists of three components:

- Cue – The trigger that initiates the behavior

- Routine – The behavior itself

- Reward – The reinforcement that strengthens the habit

Example:

- Cue: Stress after work

- Routine: Scrolling social media

- Reward: Mental distraction and emotional relief

Learning theory explains that the reward is the teacher. It signals to the brain that the routine is worth repeating whenever the cue appears again. Over repeated cycles, the brain begins to anticipate the reward as soon as the cue is detected, which is why urges arise automatically.

Psychological Insight

Habits do not persist because people lack discipline. They persist because the brain has learned efficiently. Understanding reinforcement and the habit loop shifts the focus from self-blame to strategic change—modifying cues, routines, or rewards rather than relying on willpower alone.

From a learning theory perspective, to change a habit is not to fight the brain, but to retrain it.

Social Learning Theory and Habit Formation

Conclusion

Habit formation is best understood through learning theory. Classical conditioning explains how cues trigger automatic responses. Operant conditioning explains why behaviors persist through reinforcement. Social learning theory explains how habits are modeled and transmitted socially.

Habits are not accidents—they are learned patterns shaped by experience, emotion, and environment. When habits are understood through learning theory, change becomes possible through structured, compassionate, and evidence-based approaches.

Habits can be unlearned—not by force, but by learning something new.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is habit formation in psychology?

Habit formation is the process by which repeated behaviors become automatic responses to specific cues through learning, reinforcement, and repetition.

2. How does learning theory explain habits?

Learning theory explains habits as learned behaviors shaped by environmental cues, reinforcement (rewards or relief), and observation of others.

3. What role does classical conditioning play in habits?

Classical conditioning explains how neutral cues (like time, place, or sounds) become associated with emotional or physiological responses that trigger habitual behavior.

4. How is operant conditioning related to habit formation?

Operant conditioning explains how habits are strengthened or weakened based on consequences—behaviors followed by rewards or relief are repeated.

5. What is the difference between positive and negative reinforcement?

Positive reinforcement adds a reward to increase behavior, while negative reinforcement removes discomfort to increase behavior.

6. Why do unhealthy habits persist even when we know they are harmful?

Because they often provide immediate emotional relief or comfort, which strongly reinforces the behavior despite long-term negative consequences.

7. What is the habit loop in psychology?

The habit loop consists of a cue (trigger), routine (behavior), and reward (reinforcement), which together maintain habitual behavior.

8. How does social learning theory influence habits?

People learn habits by observing parents, peers, teachers, or media figures, especially when the model is admired or perceived as successful.

9. Why are habits hard to break?

Habits are resistant due to intermittent reinforcement, emotional relief, strong contextual cues, and lack of equally rewarding alternatives.

10. Can habits be changed using learning theory?

Yes. Habit change involves modifying cues, replacing routines, and providing consistent and meaningful reinforcement.

11. Is habit change only about willpower?

No. Learning theory shows that habit change is about retraining learned patterns, not increasing self-control or discipline.

12. How long does it take to form a habit?

There is no fixed timeline. Habit formation depends on frequency, reinforcement, emotional relevance, and environmental consistency.

13. What part of the brain controls habits?

The basal ganglia play a key role in storing and executing habitual behaviors automatically.

14. How is habit formation used in therapy?

Therapies like CBT, behavioral activation, and addiction treatment use learning principles to build healthier habits.

15. Why is understanding habit formation important for mental health?

It reduces self-blame, increases self-compassion, and empowers individuals to create sustainable behavioral change.

Written by Baishakhi Das

Counselor | Mental Health Practitioner

B.Sc, M.Sc, PG Diploma in Counseling

Reference

-

American Psychological Association (APA) – Learning & Behavior

https://www.apa.org -

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and Human Behavior

https://www.bfskinner.org -

Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory

https://www.simplypsychology.org/bandura.html -

Pavlov, I. P. (1927). Conditioned Reflexes

https://www.simplypsychology.org/classical-conditioning.html -

Wood, W., & Neal, D. T. (2007). A New Look at Habits – Psychological Review

https://psycnet.apa.org -

National Institute of Mental Health – Behavior Change

https://www.nimh.nih.gov - Burnout in Working Men: Signs and Recovery

This topic performs well due to rising searches around men’s mental health, workplace stress, and burnout recovery. Combining emotional insight with practical steps increases engagement and trust.