Trauma is not just something that happens to a person—it is something that lives inside the brain and body long after the event has passed. Many survivors find themselves asking, “Why am I still affected when it’s over?” or “Why can’t I just move on?” Trauma theory explains that these reactions are not signs of weakness or overthinking. They are the result of how the brain is designed to protect us during overwhelming experiences.

When an experience feels threatening, inescapable, or emotionally overwhelming, the brain shifts from everyday processing into survival mode. In this state, the priority is not understanding or meaning-making, but immediate safety. As a result, traumatic experiences are processed and stored differently from ordinary life events. The brain does not file them away as memories of the past—it keeps them close, ready to be reactivated if danger is sensed again.

Unlike ordinary memories, traumatic experiences are encoded not only as thoughts or stories, but as sensations, emotions, bodily reactions, and survival responses. A smell, sound, tone of voice, or emotional state can trigger intense reactions even when the person consciously knows they are safe. This is why trauma often shows up as anxiety, numbness, flashbacks, or sudden emotional flooding rather than clear recollections.

This article explores trauma theory to explain how the brain stores pain, why trauma symptoms persist long after the event has ended, and why these responses once served a protective function. Most importantly, it also explains how healing becomes possible—by helping the brain and nervous system learn that the danger has passed and that safety can be experienced again.

What Is Trauma in Psychology?

In psychology, trauma refers to an experience that overwhelms a person’s capacity to cope, process emotions, or maintain a sense of safety. Trauma is not defined solely by what happened, but by how the nervous system experienced and responded to the event. When the brain perceives danger without adequate resources for protection or escape, it shifts into survival mode, and trauma may develop.

This is why trauma is better understood as a physiological and psychological response, rather than a measure of how “serious” an event appears from the outside.

Trauma can result from a wide range of experiences, including:

- Abuse or neglect – emotional, physical, or sexual, especially during childhood

- Accidents or medical trauma – surgeries, invasive procedures, or sudden injuries

- Sudden loss or grief – death of a loved one, separation, or abandonment

- Chronic emotional invalidation – repeated dismissal of feelings, needs, or identity

- Exposure to violence or threat – domestic violence, community violence, or disasters

Importantly, two people may experience the same event, yet only one develops trauma. This is because trauma depends on perceived threat, helplessness, and loss of safety, not objective severity. Factors such as age, prior experiences, emotional support, and the availability of safety during or after the event all influence how the nervous system encodes the experience.

Trauma, therefore, is not a sign of weakness—it is evidence that the brain and body were pushed beyond their limits and did what they could to survive.

Trauma Theory: A Core Psychological Framework

This theory is an integrative framework that draws from neuroscience, developmental psychology, and clinical practice to explain how overwhelming experiences affect the mind and body. Rather than viewing trauma as a failure to cope, modern psychology understands it as an adaptive survival response shaped by the brain’s attempt to protect the individual from threat.

Key contributors who shaped trauma theory include:

- Sigmund Freud – introduced early ideas about traumatic memory, repression, and the mind’s attempt to keep overwhelming experiences out of awareness

- Judith Herman – conceptualized trauma as a condition of disempowerment and disconnection and outlined stages of recovery: safety, remembrance, and reconnection

- Bessel van der Kolk – emphasized that trauma is stored not only as memory, but as bodily sensation and nervous system dysregulation

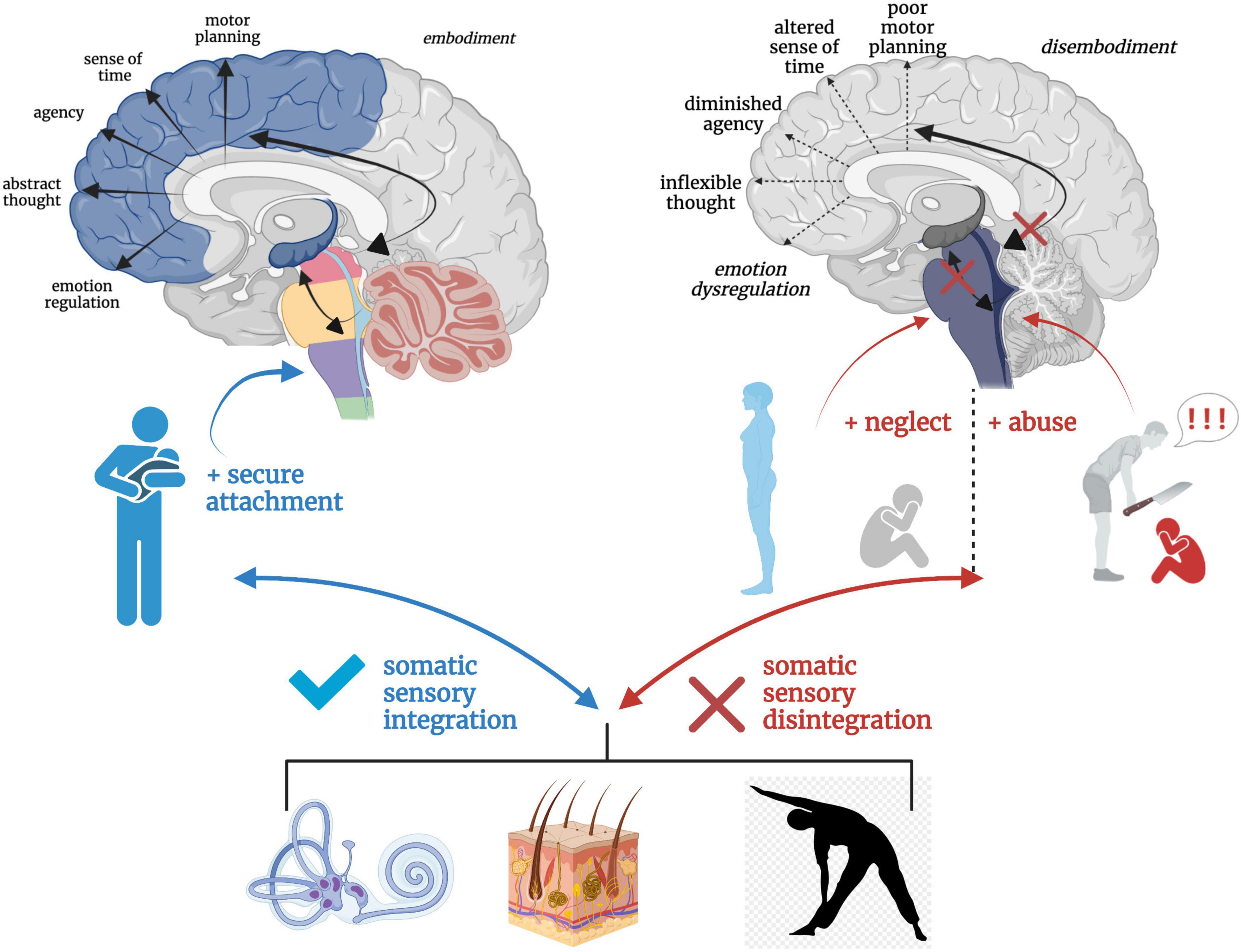

Modern trauma theory moves beyond purely psychological explanations and emphasizes that trauma is a biological and neurological survival response. Symptoms such as hypervigilance, dissociation, emotional numbing, or flashbacks are not signs of weakness or flawed character—they are evidence of a nervous system that adapted under extreme conditions.

How the Brain Normally Stores Memory

Under non-threatening conditions, the brain processes and stores experiences in an organized and integrated way. Multiple brain regions work together to ensure that memories are placed firmly in the past.

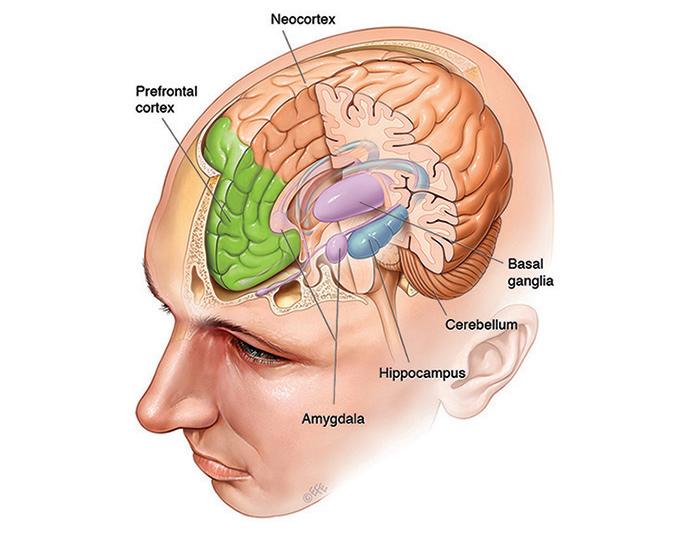

Key roles include:

- Hippocampus – encodes memory with time, place, and context, allowing events to be remembered as something that already happened

- Prefrontal cortex – helps interpret experiences, regulate emotions, and apply logic and perspective

- Amygdala – assesses emotional significance and alerts the brain to potential threat

When these systems function together, memories are stored as narratives rather than alarms. A person can recall the event, reflect on it, and recognize that it belongs to the past. Emotional reactions remain proportionate, and the body does not respond as if danger is occurring in the present.

Trauma theory highlights that when an experience overwhelms this system, the brain’s normal memory processing breaks down—leading to the distinctive and often distressing way traumatic pain is stored and later reactivated.

How the Brain Stores Traumatic Pain Differently

When an experience feels life-threatening or overwhelming, the brain shifts into survival mode.

1. Amygdala: The Fear Alarm

The amygdala becomes hyperactive during trauma. Its job is to detect danger and activate survival responses.

- Prioritizes speed over accuracy

- Stores emotional intensity, not narrative detail

- Remains sensitive even after the threat is gone

This is why trauma survivors may feel fear or panic without knowing why.

2. Hippocampus: Fragmented Memory Storage

During trauma, the hippocampus often goes offline.

- Memories are stored without time stamps

- Events feel ongoing rather than past

- Sensory fragments replace coherent stories

This explains flashbacks, intrusive images, or body sensations that feel as if the trauma is happening now.

3. Prefrontal Cortex: Loss of Regulation

The prefrontal cortex, responsible for reasoning and emotional regulation, becomes less active during trauma.

- Logical thinking decreases

- Language access reduces

- Emotional regulation weakens

This is why trauma responses often feel irrational, overwhelming, and uncontrollable.

The Body Remembers What the Mind Cannot

One of the most important insights of trauma theory is that trauma is stored in the body, not just the mind. Many trauma survivors struggle to explain their distress because they may not have clear memories or words for what happened—yet their bodies continue to react as if danger is present.

According to Bessel van der Kolk, traumatic memory is often encoded as sensory and physiological experience, rather than as a coherent story. This is why trauma may appear through physical and emotional symptoms long after the event has ended.

Trauma memory may show up as:

- Chronic muscle tension – the body remains braced for threat

- Digestive issues – the gut reacts to prolonged stress

- Fatigue or emotional numbness – shutdown as a form of protection

- Hypervigilance – constant scanning for danger

- Dissociation – disconnection from body, emotions, or surroundings

In these states, the nervous system has learned that staying alert—or shutting down—is necessary for survival, even when the person is objectively safe.

Trauma and the Nervous System

Trauma deeply affects the autonomic nervous system, which controls automatic survival responses. When trauma occurs, this system may become dysregulated, keeping the body locked in survival mode.

Common trauma-related survival states include:

- Fight – anger, irritability, defensiveness, control

- Flight – avoidance, restlessness, anxiety, overworking

- Freeze – numbness, dissociation, low energy, collapse

- Fawn – people-pleasing, compliance, prioritizing others to stay safe

These reactions are not conscious choices or personality flaws. They are learned survival responses that once protected the individual in unsafe situations.

Trauma theory emphasizes that the nervous system does not respond to logic—it responds to perceived safety.

Why Trauma Feels Timeless

Traumatic memories are often stored without a clear sense of time. Because the hippocampus does not fully integrate the experience, the brain cannot easily recognize it as something that happened in the past.

As a result, the body reacts as if the threat is happening now.

This leads to:

- Emotional overreactions that feel disproportionate

- Triggers that seem minor or confusing

- Strong bodily reactions without conscious memory or explanation

Therefore not simply remembered—it is relived through sensations, emotions, and automatic responses.

Trauma Is Not a Memory Problem—It’s a Safety Problem

This theory reframes symptoms such as anxiety, dissociation, emotional numbness, and hyperarousal as adaptive responses, not pathology.

At its core, the traumatized brain is constantly asking:

“Am I safe right now?”

Until the nervous system receives consistent signals of safety, trauma symptoms persist—not because the person is stuck, but because the brain is still trying to protect.

Healing Trauma: Reprocessing Pain in the Brain

Healing does not mean erasing traumatic memories or forcing oneself to “move on.” Instead, healing involves integrating traumatic experiences safely, so they can be stored as past events rather than present threats.

Effective trauma-informed approaches include:

- Trauma-focused CBT – restructuring trauma-related beliefs while building regulation

- EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) – helping the brain reprocess stuck traumatic memory

- Somatic therapies – restoring safety through the body and nervous system

- Mindfulness and grounding techniques – anchoring awareness in the present moment

These approaches work by reconnecting brain regions involved in memory, emotion, and regulation, allowing the nervous system to stand down from constant alert.

Clinical and Counseling Relevance

In therapeutic practice, understanding how the brain and body store trauma helps clinicians and clients to:

- Reduce shame and self-blame

- Normalize trauma responses as protective adaptations

- Prioritize regulation and safety before insight

- Pace healing in a way that prevents retraumatization

Trauma recovery is not about “getting over it.”

It is about teaching the brain and body that the danger has passed—and that safety is possible now.

Healing begins not with force, but with safety, understanding, and compassion.

Conclusion

Trauma theory shows that pain is not stored as a simple memory—it is stored as emotion, sensation, and survival learning. The brain does exactly what it is designed to do: protect.

Trauma symptoms are not signs of weakness. They are signs of a nervous system that learned to survive.

With safety, support, and trauma-informed care, the brain can learn again—this time, that it is safe to rest.

Healing begins when pain is understood, not judged.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is trauma in psychology?

Trauma is a psychological and physiological response to an overwhelming experience that threatens a person’s sense of safety and exceeds their ability to cope.

2. Is trauma defined by the event or the reaction?

Trauma is defined by the nervous system’s response, not the event itself. The same event may be traumatic for one person and not for another.

3. How does the brain store traumatic memories?

Traumatic memories are stored as sensations, emotions, and survival responses, rather than organized narratives with time and context.

4. Why do trauma symptoms continue long after the event?

Because the brain and nervous system remain in survival mode, reacting as if the threat is still present.

5. What role does the amygdala play in trauma?

The amygdala detects danger and becomes hyperactive during trauma, triggering fear and alert responses even in safe situations.

6. Why do trauma memories feel like they are happening now?

Trauma memories lack proper time-stamping by the hippocampus, so the brain cannot clearly distinguish past from present.

7. How is trauma stored in the body?

Trauma can appear as muscle tension, digestive issues, fatigue, hypervigilance, or dissociation due to nervous system dysregulation.

8. What are fight, flight, freeze, and fawn responses?

They are automatic survival responses activated by the nervous system to manage perceived threat, not conscious choices.

9. Is trauma a memory problem?

No. Trauma is primarily a safety problem, where the brain continues to prioritize protection over calm functioning.

10. Why do small triggers cause intense reactions?

Triggers activate stored trauma responses, causing the nervous system to react as if the original danger has returned.

11. Can trauma be healed?

Yes. Trauma can be healed by helping the brain and body relearn safety and integrate traumatic memories.

12. Does healing mean forgetting the trauma?

No. Healing means remembering the experience without reliving it emotionally or physically.

13. What therapies help with trauma recovery?

Trauma-focused CBT, EMDR, somatic therapies, and mindfulness-based approaches are commonly used.

14. Why is regulation important before insight in trauma therapy?

Because the nervous system must feel safe before reflection, memory processing, or emotional exploration is possible.

15. Is trauma a sign of weakness?

No. Trauma responses are signs of a protective nervous system, not personal failure or weakness.

Written by Baishakhi Das

Counselor | Mental Health Practitioner

B.Sc, M.Sc, PG Diploma in Counseling

Reference

-

American Psychological Association – Trauma

https://www.apa.org/topics/trauma -

National Institute of Mental Health – PTSD & Trauma

https://www.nimh.nih.gov -

van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score

https://www.besselvanderkolk.com -

Herman, J. (1992). Trauma and Recovery

https://www.judithherman.com -

Porges, S. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory

https://www.polyvagalinstitute.org -

Siegel, D. J. (2012). The Developing Mind

https://drdansiegel.com -

Simply Psychology – Trauma & Memory

https://www.simplypsychology.org - Burnout in Working Men: Signs and Recovery

This topic performs well due to rising searches around men’s mental health, workplace stress, and burnout recovery. Combining emotional insight with practical steps increases engagement and trust.