Understanding How Early Bonds Shape Emotional Development

A child’s first relationship—usually with a parent or primary caregiver—plays a powerful role in shaping how they understand love, trust, safety, and emotional connection. From the moment a baby is born, they begin forming impressions about the world: Is it safe? Will someone respond when I cry? Do my needs matter?

This early emotional bond is known as attachment, and it is one of the most important foundations of a child’s development. Attachment is not just a feeling—it’s a biological and psychological process that influences how the brain grows, how emotions are regulated, and how relationships are formed throughout life.

When caregivers are responsive, comforting, and emotionally attuned, children learn that the world is a secure place. But when caregiving is inconsistent, distant, or frightening, children adapt in different ways—sometimes by becoming overly clingy, sometimes by shutting down their emotions, and sometimes by showing confused or disorganized responses.

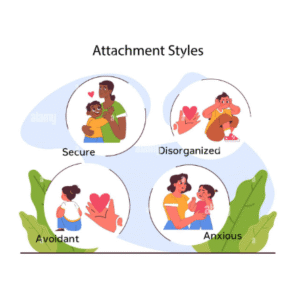

Because of these varied adaptations, psychologists generally categorize childhood attachment into four main styles:

1. Secure Attachment

2. Avoidant Attachment

3. Ambivalent (Resistant) Attachment

4. Disorganized Attachment

Each attachment style develops based on the child’s everyday experiences—how often they are comforted when distressed, how their emotions are responded to, and how predictable or unpredictable their caregivers are. These patterns shape the child’s sense of self, their ability to connect with others, and their emotional resilience well into adulthood.

In essence, attachment is the first lesson a child learns about relationships—

“Can I rely on others, and am I worthy of care?”

Understanding these attachment styles helps parents, teachers, and mental health professionals support healthier emotional development and repair insecure patterns early.

1. Secure Attachment: The Foundation of Emotional Well-being

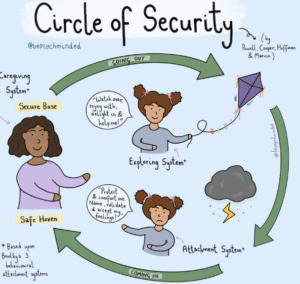

Children with secure attachment grow up feeling safe, protected, valued, and emotionally understood. This style forms when a child consistently experiences warmth, comfort, and predictable care. As a result, they begin to trust that their emotional needs will be met, which becomes the cornerstone of healthy emotional development.

Why Secure Attachment Develops

Secure attachment is not about being a “perfect parent”—it’s about being consistently responsive and emotionally present. It develops when:

- Caregivers respond consistently

The child learns that their signals—crying, reaching out, seeking closeness—will be acknowledged rather than ignored. - Emotional needs are met

When the child feels scared, overwhelmed, or uncomfortable, the caregiver responds with empathy and support. - Comfort is provided during distress

The caregiver becomes a “safe base” where the child receives soothing, reassurance, and physical closeness when needed. - Caregiver is warm, predictable, and available

Daily interactions such as smiling, talking, playing, and maintaining eye contact help the child feel emotionally connected and secure.

Through these repeated experiences, the child’s brain wires itself to expect safety, trust, and connection in relationships.

How a Securely Attached Child Behaves

Securely attached children show a healthy balance between independence and connection:

- Explores the environment confidently

They are curious and adventurous because they know they can return to their caregiver if they feel unsure. - Seeks comfort from caregiver when upset

They don’t hesitate to ask for help, which shows trust in the caregiver. - Easily soothed

After receiving comfort, they calm down quickly and return to play or exploration. - Shows a strong preference for the caregiver but is not clingy

They enjoy closeness but also feel confident enough to separate and explore. - Builds healthy peer relationships

Because they feel secure in themselves, they interact better with other children—sharing, taking turns, and forming friendships.

Long-Term Impact of Secure Attachment

Secure attachment supports long-lasting emotional, social, and cognitive development. Children who grow up with secure attachment often show:

- Good self-esteem

They feel worthy of love and believe their feelings matter. - Strong emotional regulation

They can identify, express, and manage feelings more effectively. - Healthy relationships

They form trusting bonds with peers, partners, teachers, and later in life, colleagues and romantic partners. - Better academic and social skills

Their emotional stability helps them concentrate, participate in class, and communicate more effectively.

2. Avoidant Attachment: Independence with Hidden Anxiety

Avoidant attachment develops when a child repeatedly learns that expressing emotions is not safe, welcome, or effective. On the surface, these children may appear unusually independent or “low-maintenance,” but internally, they have learned to suppress their emotional needs to avoid rejection or disappointment.

Why Avoidant Attachment Develops

Avoidant attachment typically emerges when the caregiver is physically present but emotionally unavailable. This can happen when:

- The caregiver is distant, dismissive, or emotionally unavailable

They may care for the child’s physical needs but rarely respond to emotional cues such as crying, fear, or sadness. - The child’s feelings are minimized or dismissed

Statements like “Stop crying”, “You’re fine”, or “Don’t make a fuss” teach the child that emotions are unacceptable or inconvenient. - Comfort is not consistently offered

The child gradually learns that seeking closeness or reassurance does not lead to comfort, so they stop trying.

Over time, the child adapts by turning inward and relying on themselves—not because they don’t need connection, but because they assume it is unavailable.

How the Child Behaves

Children with avoidant attachment often display a surprising level of independence for their age:

- Appears very independent

They may prefer playing alone and managing situations without seeking help. - Avoids closeness or physical contact

Hugs, cuddles, or affectionate gestures may make them uncomfortable. - Doesn’t seek comfort when distressed

Even when hurt or scared, they suppress the instinct to reach out. - Shows little reaction when the caregiver leaves or returns

This does not mean they don’t care—it means they learned to hide their distress.

These behaviors are coping mechanisms, not signs of emotional strength.

What’s Happening Internally

Even though they appear calm or detached, internally the child may be experiencing confusion, frustration, or anxiety.

The internal message becomes:

“My feelings won’t be understood or supported—

so it’s safer to handle things alone.”

Instead of learning emotional expression, they learn emotional avoidance.

Long-Term Impact

If avoidant attachment continues into later childhood or adulthood, it may shape emotional and relational patterns such as:

- Difficulty expressing emotions

They struggle to identify or share their feelings, often appearing emotionally “flat.” - Preference for emotional distance

Close relationships can feel overwhelming or uncomfortable. - Discomfort with dependency or vulnerability

They resist relying on others and may pull away when relationships feel too intimate.

Although these children may seem self-sufficient, they often carry unmet emotional needs beneath the surface.

3. Ambivalent (Resistant) Attachment: Clinginess & Uncertainty

Ambivalent attachment develops when a child experiences inconsistent caregiving—moments of warmth followed by moments of emotional unavailability. Because the child never knows whether their needs will be met, they become anxious, overly alert, and dependent on the caregiver for reassurance.

Why Ambivalent Attachment Develops

This attachment style forms when the caregiver’s attention and emotional availability are unpredictable. The child may receive love and comfort at times, but at other times, the caregiver may be distracted, overwhelmed, or unresponsive.

- The caregiver is sometimes loving, sometimes unavailable

The child cannot rely on consistent comfort or presence. - The child cannot predict when they will receive attention

This unpredictability creates emotional confusion and insecurity. - Emotional needs are met inconsistently

Sometimes the caregiver responds quickly; other times the child’s distress is ignored or misread.

Because of this inconsistency, the child becomes hyper-focused on the caregiver’s availability, trying harder and harder to get their attention.

How the Child Behaves

Children with ambivalent attachment often appear needy, clingy, or emotionally intense, but these behaviors are rooted in fear and confusion:

- Very clingy or “hyper-attached”

They stay close to the caregiver, fearing separation or rejection. - Becomes extremely distressed when the caregiver leaves

Even short separations trigger strong emotional reactions. - Hard to soothe even when the caregiver returns

They may cling but also resist comfort—crying, pushing away, or showing anger. - Appears anxious, insecure, or demanding

They express big emotions and rely heavily on the caregiver for reassurance.

This pattern reflects their internal struggle to feel safe in a relationship that feels unpredictable.

What’s Happening Internally

Because they cannot rely on consistent caregiving, these children develop intense anxiety around separation and connection.

Their internal belief becomes:

“I don’t know when you’ll be there for me…

so I must cling tightly to make sure you don’t leave.”

This creates emotional hypervigilance—constantly checking for signs of love, attention, or abandonment.

Long-Term Impact

If ambivalent attachment continues without support or intervention, children may carry these emotional patterns into later life:

- Heightened emotional sensitivity

They feel emotions intensely and may struggle to self-soothe. - Fear of abandonment

They may worry excessively about losing relationships or being left alone. - Difficulty with boundaries in relationships

They may become overly dependent, controlling, or anxious in close relationships.

Although their behaviors may seem dramatic, these children are simply trying to feel secure in a relationship that feels uncertain.

4. Disorganized Attachment: Fear Without Solution

Disorganized attachment is considered the most complex and concerning attachment style because it develops when a child’s primary source of safety is also a source of fear. In this situation, the child’s attachment system becomes overwhelmed and confused, leading to chaotic or contradictory behaviors.

This style is often associated with significant stress, trauma, or disrupted caregiving patterns.

Why Disorganized Attachment Develops

Disorganized attachment forms when the caregiver—who should be a protector—becomes unpredictable, frightening, or emotionally unsafe. This leaves the child without a clear strategy for seeking comfort or security.

It often develops when:

- The caregiver is frightening, unpredictable, or abusive

The child may see threatening facial expressions, sudden anger, or aggression. - The child experiences trauma, neglect, or chronic stress

Their nervous system becomes overwhelmed, making emotional regulation difficult. - The caregiver is both a source of comfort and fear

The child becomes confused: they want closeness, but they also want to escape. - There is household chaos or violence

Exposure to conflict, substance abuse, or instability disrupts the child’s sense of safety.

These mixed signals leave the child with no consistent way to seek help or feel protected.

How the Child Behaves

Children with disorganized attachment often display confusing, unpredictable, or contradictory behaviors. These behaviors reflect inner turmoil rather than intentional defiance.

Common behaviors include:

- Confusing or contradictory actions

Such as freezing, running away from the caregiver, rocking back and forth, or approaching and then suddenly withdrawing. - Fearful of the caregiver

The child may show fear, flinching, or avoidance when the caregiver approaches. - Appears disoriented or overwhelmed

They may stare blankly, seem “shut down,” or appear disconnected from their surroundings. - Sudden mood shifts

Rapid changes from clinginess to withdrawal, or from calm to distressed, are common.

These behaviors are survival strategies in an environment that feels emotionally unsafe or unpredictable.

What’s Happening Internally

Inside, the child faces a painful and confusing paradox:

“The person who should protect me is the one I fear.”

The child’s attachment system becomes disorganized because they have no safe, predictable way to regulate emotions or seek comfort. Their brain shifts into survival mode—fight, flight, freeze, or dissociate.

Long-Term Impact

Without intervention or supportive caregiving, disorganized attachment may contribute to more serious emotional and behavioral challenges later in life:

- Higher risk for emotional dysregulation

Difficulty managing stress, fear, anger, and sadness. - Behavioral difficulties

Aggression, oppositional behavior, withdrawal, or impulsivity. - Dissociation or trauma-related symptoms

Spacing out, feeling disconnected from the body, nightmares, or trauma responses. - Difficulty forming stable relationships

Trouble trusting others, controlling behaviors, fear of intimacy, or chaotic relationship patterns.

Despite these risks, healing is absolutely possible with consistent caregiving, therapy, and trauma-informed support.

How Parents & Caregivers Can Build Secure Attachment

No parent is perfect—and attachment has never been about perfection. It is about the everyday consistency, emotional presence, and genuine responsiveness that help a child feel seen and supported. Children don’t need flawless parenting; they need caregivers who try, who show up, and who repair when things go wrong.

What Helps Build Secure Attachment

Simple, repeated acts of care can strengthen a child’s sense of safety and trust:

✔ Responding to emotional needs promptly

Helps the child feel that their feelings matter and will be taken seriously.

✔ Offering comfort without judgment

Accepting emotions—rather than criticizing or dismissing them—teaches children emotional safety.

✔ Creating predictable routines

Daily structure gives children a sense of stability and reduces anxiety.

✔ Showing warmth through touch, voice, and presence

A gentle tone, a warm hug, or engaged eye contact reassures the child that they are loved.

✔ Encouraging independence with support

Letting children explore freely while being available when needed builds confidence.

✔ Repairing conflicts (apologizing, reconnecting)

When misunderstandings or conflicts happen, reconnecting teaches the child that relationships can heal.

The Hopeful Truth: Attachment Can Change

Even if a child currently shows insecure attachment patterns, these are not permanent labels. With consistent, nurturing caregiving and, when needed, professional therapeutic support, children can develop more secure attachment over time. The brain is adaptable, relationships can be repaired, and emotional patterns can heal.

Every warm interaction, every moment of attunement, and every effort to understand a child’s feelings contributes to shaping a more secure, resilient future.

Final Thoughts

Understanding attachment styles empowers parents, teachers, and mental health professionals to create safe, nurturing emotional environments for children. When caregivers recognize the patterns behind children’s behaviors—whether clinginess, withdrawal, fear, or confusion—they can respond with greater patience, empathy, and insight.

Early attachment experiences lay the foundation for how children learn to trust others, connect meaningfully, regulate their emotions, and build stable relationships throughout life. These first bonds shape not only emotional well-being, but also social development, self-esteem, and resilience.

The hopeful truth is that attachment is not fixed. With awareness, consistency, and psychological guidance, caregivers can strengthen or repair attachment patterns at any age. Through warmth, presence, and responsive caregiving, it is always possible to nurture healthier bonds and support a child’s journey toward emotional security and lifelong resilience.

Reference

American Psychological Association (APA) – Attachment Theory

https://www.apa.org/monitor/2019/05/ce-corner-attachment

2Harvard University – Center on the Developing Child

https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/serve-and-return/

National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN)

Counselling support → Contact Us