Understanding two major approaches to human behavior and the mind

Introduction

Psychology has evolved through multiple schools of thought, each attempting to explain why humans think, feel, and behave the way they do. These perspectives developed in response to different questions—some focusing on what can be observed and measured, others exploring the invisible workings of the mind. Among these, Behaviorism and Cognitive Psychology stand out as two of the most influential—and contrasting—approaches in the history of psychology.

Behaviorism emerged in the early 20th century as a reaction against introspective methods. It argues that psychology should focus only on observable behavior and external consequences, because these can be scientifically measured and objectively studied. From this perspective, human behavior is shaped largely by the environment through learning, reinforcement, and punishment.

In contrast, Cognitive Psychology developed later, emphasizing that behavior cannot be fully understood without examining internal mental processes. It focuses on how people think, remember, interpret, problem-solve, and make meaning of their experiences. Cognitive psychologists view humans as active processors of information, whose beliefs, perceptions, and thoughts strongly influence emotions and actions.

Understanding the differences between behaviorism and cognitive psychology is essential for students, educators, therapists, and mental health practitioners, because these approaches influence how learning is taught, how behavior is managed, and how psychological difficulties are treated. Modern psychology increasingly integrates both perspectives, recognizing that behavior is shaped by external experiences and internal cognition working together, rather than by one alone.

What Is Behaviorism?

Behaviorism is a psychological approach that explains behavior as a result of environmental stimuli and learned responses. It argues that psychology should focus only on observable, measurable behavior, because behavior can be objectively studied, predicted, and controlled. From this viewpoint, internal mental states—such as thoughts, feelings, or intentions—are considered unnecessary for explaining behavior, as they cannot be directly observed.

Behaviorism emerged as a reaction against introspection-based psychology and aimed to make psychology a scientific, experimental discipline, similar to the natural sciences.

Key Contributors

-

John B. Watson – Founder of behaviorism; emphasized stimulus–response learning

-

B. F. Skinner – Developed operant conditioning; highlighted reinforcement and punishment

-

Ivan Pavlov – Discovered classical conditioning through conditioned reflexes

Each contributed to understanding how learning occurs through interaction with the environment.

Core Assumptions of Behaviorism

Behaviorism is based on several fundamental assumptions:

-

Behavior is learned, not innate

Humans are not born with fixed behavioral patterns; behavior develops through experience. -

Learning occurs through conditioning

Repeated associations and consequences shape behavior. -

Internal thoughts are not necessary to explain behavior

Only observable actions are required for scientific explanation. -

The environment shapes behavior

External stimuli, rewards, and punishments determine how individuals act.

Key Concepts in Behaviorism

-

Classical Conditioning

Learning through association between stimuli (e.g., Pavlov’s experiments). -

Operant Conditioning

Learning through consequences—reinforcement and punishment (Skinner). -

Reinforcement and Punishment

Consequences that increase or decrease behavior. -

Stimulus–Response (S–R) Associations

Behavior is seen as a direct response to environmental stimuli.

Example

A child studies more because good marks are rewarded.

→ The increased studying is explained through reinforcement, not through motivation, self-belief, or emotions.

From a behaviorist perspective, the reward strengthens the behavior, making internal thoughts unnecessary for explanation.

Key Insight

Behaviorism provides a clear, practical framework for understanding and modifying behavior, especially in areas like education, parenting, and behavior therapy. However, its focus on observable behavior alone is also what later led to the development of approaches—like cognitive psychology—that explore what happens inside the mind.

What Is Cognitive Psychology?

Cognitive psychology is a branch of psychology that focuses on how people process information—including thinking, reasoning, memory, attention, language, perception, and problem-solving. Rather than viewing humans as passive responders to external stimuli, this approach sees individuals as active processors of information who interpret, evaluate, and make meaning from their experiences.

Cognitive psychology emerged as a response to the limitations of behaviorism. Psychologists realized that understanding behavior requires exploring what happens inside the mind—how people think about situations, how they remember past experiences, and how they interpret the world around them.

Key Contributors

-

Jean Piaget – Explained how children’s thinking develops through distinct cognitive stages

-

Aaron Beck – Developed cognitive therapy, highlighting how thoughts influence emotions and behavior

Their work laid the foundation for understanding learning, development, and mental health through cognitive processes.

Core Assumptions of Cognitive Psychology

Cognitive psychology is built on several key assumptions:

-

Mental processes influence behavior

What people think directly affects how they feel and act. -

Thoughts, beliefs, and interpretations matter

The same situation can lead to different behaviors depending on how it is perceived. -

Humans actively construct meaning

People are not passive learners; they organize and interpret information based on prior knowledge. -

Behavior cannot be fully understood without understanding cognition

Observable behavior is only one part of the picture—internal processes give it meaning.

Key Concepts in Cognitive Psychology

-

Schemas

Mental frameworks that help organize and interpret information (e.g., beliefs about self or others). -

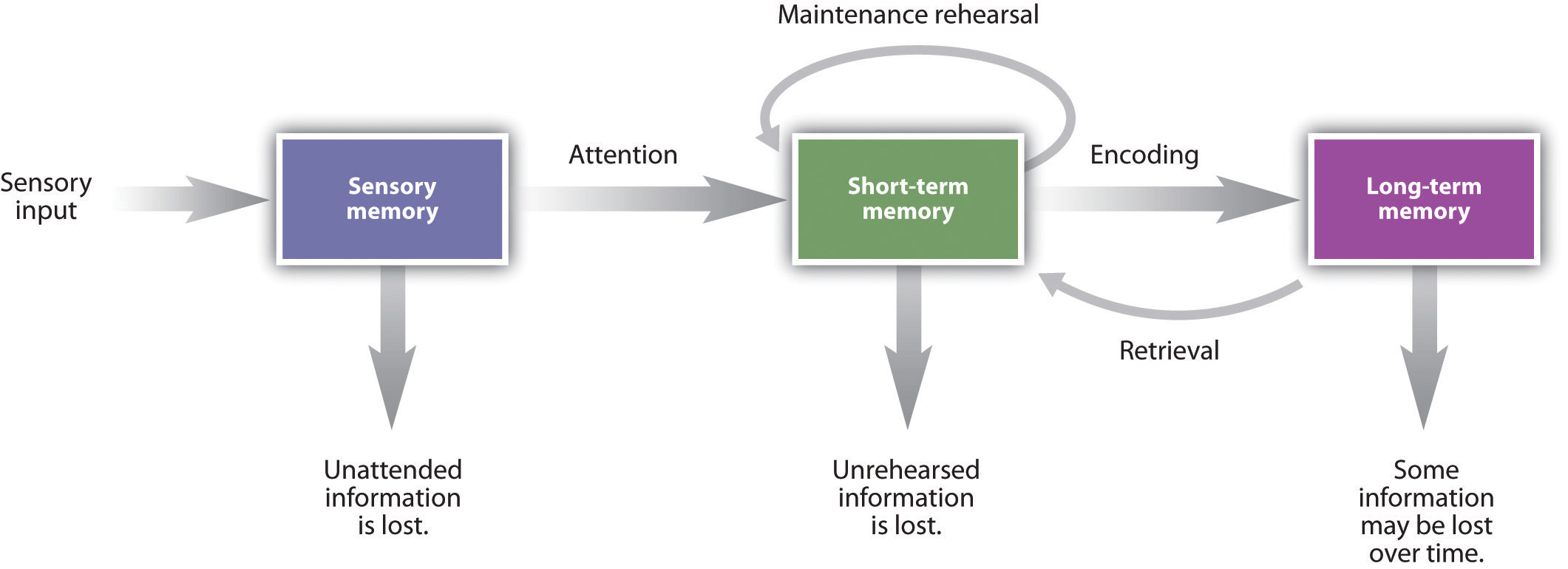

Information Processing

The way the mind encodes, stores, and retrieves information—often compared to a computer model. -

Cognitive Distortions

Inaccurate or biased thinking patterns that influence emotions and behavior. -

Memory and Attention

Processes that determine what information is noticed, remembered, or forgotten.

Example

A child avoids studying because they think, “I’m not smart enough.”

→ From a cognitive perspective, the behavior is explained by beliefs, self-perception, and thought patterns, not by rewards or punishment alone.

The problem is not just the behavior (avoiding study), but the underlying cognition shaping it.

Key Insight

Cognitive psychology helps us understand why behavior occurs, not just how it changes. By addressing thoughts, beliefs, and interpretations, this approach is especially valuable in education, counseling, and mental health interventions, where insight and emotional understanding are essential for lasting change.

Key Differences: Behaviorism vs Cognitive Psychology

| Aspect | Behaviorism | Cognitive Psychology |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Observable behavior | Internal mental processes |

| View of mind | Not necessary to study | Central to behavior |

| Learning | Conditioning | Information processing |

| Role of environment | Primary influence | Important but not sole factor |

| Role of thoughts | Ignored | Essential |

| Research methods | Experiments, observation | Experiments, models, self-report |

| Therapy focus | Behavior change | Thought + behavior change |

Applications in Real Life

In Education

Both approaches strongly influence how teaching and learning are designed.

-

Behaviorism emphasizes observable performance.

-

Reward-based learning (grades, praise, stars)

-

Discipline systems with clear rules and consequences

-

Repetition and practice to build habits

This approach is especially useful for classroom management, skill acquisition, and maintaining structure.

-

-

Cognitive Psychology focuses on how students think and understand.

-

Learning strategies (mnemonics, mind maps)

-

Problem-solving and critical thinking

-

Conceptual understanding rather than rote learning

This helps students become active learners who understand why and how, not just what.

-

👉 Modern education blends both: reinforcement to motivate effort, and cognitive strategies to deepen understanding.

In Parenting

Parenting practices often reflect a mix of these two approaches.

-

Behaviorism in parenting involves:

-

Reinforcing good behavior (praise, attention, rewards)

-

Setting clear consequences for misbehavior

-

Consistency in responses

This helps children learn boundaries and expectations.

-

-

Cognitive Psychology in parenting focuses on:

-

Understanding emotions behind behavior

-

Helping children identify self-talk (“I can’t do this”)

-

Supporting motivation, confidence, and emotional regulation

-

👉 Together, they allow parents to guide behavior while also nurturing emotional intelligence and self-esteem.

In Therapy

Therapeutic approaches clearly show the strengths of both perspectives.

-

Behaviorism contributes:

-

Behavior modification techniques

-

Exposure therapy for fears and phobias

-

Habit reversal strategies

-

-

Cognitive Psychology contributes:

-

Cognitive restructuring (challenging negative thoughts)

-

Changing maladaptive beliefs

-

Improving self-perception and emotional understanding

-

Modern therapies—especially Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)—integrate both approaches, targeting behavior change and thought patterns simultaneously for lasting mental health improvement.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of Behaviorism

-

Clear, measurable, and practical

-

Highly effective for habit formation

-

Widely useful in classrooms, parenting, and behavior therapy

Limitations of Behaviorism

-

Ignores emotions, thoughts, and meaning

-

Limited in explaining complex human behavior

-

Less effective for trauma-related or emotionally driven issues

Strengths of Cognitive Psychology

-

Explains thinking, emotions, and meaning-making

-

Effective for anxiety, depression, and self-esteem concerns

-

Respects human agency, insight, and self-awareness

Limitations of Cognitive Psychology

-

Mental processes are harder to measure objectively

-

May overlook environmental and situational influences

-

Requires verbal ability and reflective capacity

Modern Perspective: Integration, Not Opposition

Today, psychology no longer treats behaviorism and cognitive psychology as opposing camps. Instead, they are understood as complementary perspectives.

-

Behaviorism explains how behavior is shaped through consequences and learning

-

Cognitive psychology explains why behavior happens through thoughts, beliefs, and interpretations

Integrated approaches recognize that behavior and cognition influence each other continuously.

Conclusion

Behaviorism and cognitive psychology offer two powerful lenses for understanding human behavior.

One focuses on what we do.

The other focuses on how we think.

Together, they provide a richer, more complete picture of human functioning.

Behavior can be shaped.

Thoughts can be changed.

And meaningful change happens when both are understood.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is the main difference between behaviorism and cognitive psychology?

Behaviorism focuses on observable behavior and external consequences, while cognitive psychology focuses on internal mental processes like thoughts and memory.

2. Who founded behaviorism?

Behaviorism was founded by John B. Watson.

3. Who are the major contributors to cognitive psychology?

Key contributors include Jean Piaget and Aaron Beck.

4. Why did behaviorists reject mental processes?

They believed thoughts and emotions could not be objectively measured and therefore should not be the focus of scientific psychology.

5. What does cognitive psychology focus on?

It focuses on thinking, memory, attention, perception, language, and problem-solving.

6. How does behaviorism explain learning?

Learning occurs through conditioning—via reinforcement, punishment, and stimulus–response associations.

7. How does cognitive psychology explain behavior?

Behavior is explained through beliefs, interpretations, schemas, and information processing.

8. Which approach is better for education?

Both are useful: behaviorism helps with discipline and habit formation, while cognitive psychology supports deep understanding and critical thinking.

9. Which approach is more effective in therapy?

Modern therapy combines both approaches, especially in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy.

10. Can behaviorism explain emotions?

No. One of its main limitations is ignoring emotions and internal experiences.

11. Can cognitive psychology explain habits?

Yes, but it may overlook the role of reinforcement and environment in habit formation.

12. Is behaviorism still relevant today?

Yes, especially in education, parenting, and behavior modification programs.

13. Is cognitive psychology more humanistic?

It is more person-centered than behaviorism, as it values thoughts, meaning, and insight.

14. Why are the two approaches integrated today?

Because behavior and cognition influence each other; understanding both leads to better outcomes.

15. What is the biggest takeaway from comparing these approaches?

Human behavior is best understood by combining external behavior patterns with internal mental processes.

Written by Baishakhi Das

Counselor | Mental Health Practitioner

B.Sc, M.Sc, PG Diploma in Counseling

Reference

-

Watson, J. B. (1913). Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It.

-

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and Human Behavior.

-

Piaget, J. (1952). The Origins of Intelligence in Children.

-

Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders.

-

American Psychological Association (APA) – Learning & Cognition

https://www.apa.org -

McLeod, S. A. (2023). Behaviorism & Cognitive Psychology. Simply Psychology

https://www.simplypsychology.org - Anger Issues in Men: What’s Really Going On