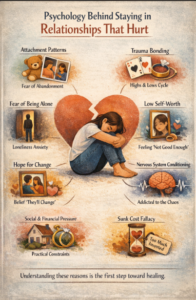

It is a question that persists among many individuals as to why a person would continue to be in a relationship that brings in emotional hurt or neglect. It is a matter of mere words, it appears that it is not so complicated, and when it hurts, one should leave. Psychology however demonstrates that maintaining is hardly weakness. They are aware that they are being hurt, they can feel it in over and over disappointments, need denials and emotional lack of companionship. Leaving is not only a logical process; it is also an emotional process and a process of the nervous system.

In the everyday life, this usually appears in the form of excuse-making over rudeness, clinging to tiny surfaces of tenderness, or wishing that things could go back to their old ways. Pain is familiar to a number of people since the relationships they had in early stages of life taught them that love is inconsistent or emotionally taxing. The unknown may be unsafe in comparison with what is familiar.

The fear of being alone, self-doubt and social pressure may silently hold people back. They could downsize the needs over the years, evade conflict, and modify themselves to the relationship. Knowledge of these patterns can be used to find an alternative to self-blame of self-compassion-and the initial step to recovery and better relationships.

1. Attachment Patterns Formed in Childhood

The experiences of being close to someone in our adulthood are influenced by our first relationships. The attachment theory states that the manner in which our emotions, needs, and distress were addressed by caregivers was a template to love and connection that would be kept as an internal record.

- In anxious attachment,

relationships usually make life worryful and prone to thinking. The fear of being deserted can be very strong due to a delay in the response, a change in the tone, or distance in nature. Human beings can be in painful relationships, as the fear of losing an individual being felt more than the pain of remaining. They can be over-giving, people-pleasing or bury their needs to ensure that the relationship remains alive. - In the avoidant attachment,

emotional distance may seem normal. Such one can manifest itself in everyday communication (reducing self-importance, not talking deeply or too closely). Negligence or emotional unavailability is not necessarily experienced as an issue since an early teaching of independence and emotional self-reliance was a source of defense. -

Fearful-avoidant attachment

tends to be confusing in push-pull fashion. Someone might want to be intimate, reassured, and close, but when he or she does, he/she will feel overwhelmed and unsafe. In real life, this might present itself as the desire to connect and then withdraw after emotional experiences, initiating fights after intimacy, or being ambivalent about remaining or leaving.

In cases where love during childhood was absent, or lacking, or conditional, the nervous system learns to be vigilant. Emotional instability can be comfortable to adults, whereas stability can be alien and even boring. What is familiar may become familiar as right, even in cases where it is painful, not because it is healthy, but because it is familiar.

Knowing these patterns of attachment makes individuals understand that their relationship problems are not personal failures, but acquired emotional reactions, and that such patterns can be addressed with understanding and secure connection.

2. Trauma Bonding and Intermittent Reinforcement

Trauma bonding is one of the potent psychological traps, as a cycle of emotional pain, after which there is a short period of affection, apology, or hope. In our everyday lives, this can be in form of constant quarrels, emotional withdrawal, and offensive behavior, followed by brief bursts of kindness, vows to change, or extreme intimacy. Such brief good moments may be a relief and very significant following a period of pain.

This tendency operates based on the intermittent reinforcement, which is the same psychological process that is observed in gambling. Since love and care cannot be forecasted, the mind will be preoccupied with the next good time to occur. The doubt leaves an individual emotionally engaged even in a case where the relationship is largely torturous.

The brain releases dopamine when one chooses to reconcile, an apology, a loving message or even when you physically get closer to a person, this is what creates a feeling of relief and emotional reward. It can even be a relief, as love. The bond becomes even stronger with time, and the reason is not that the relationship is healthy, but due to the conditioning of the nervous system to find some relief against distress.

As time passes, the relationship turns less about caring about each other and more about suffering in that quest to expand on those short periods of intercourse. Knowing about trauma bonding can make people understand that they are not addicted to an individual, it is just that they have gotten stuck in a strong cycle of psychology, which can be freed with awareness, safety, and support.

3. Fear of Loneliness and Abandonment

To a great number of individuals, the prospect of being alone is more terrifying than living in emotional distress. Loneliness may trigger profound survival anxiety, particularly in the persons who were conditioned at their early years of life that they are loved and needed and are chosen. Solitude will not only be uncomfortable, but unsafe.

This fear manifests itself in daily life in silent forms such as, at least I am not alone or this is a lot better than nothing. Individuals can remain at such relationships when they feel unnoticed or emotionally deprived just because the company of a person is better than being lonely. Common practices, communications, or even complaints may seem as comforting as nothing at all.

The relationship eventually becomes an antidote to loneliness and not a place of actual connection. The feeling needs gradually grow smaller, self-esteem is bound to the presence of the relationship, and suffering is accepted to not be alone. Coming to terms with this fear can make individuals realize that survival is frequently about being strong, rather than being weak, and that learning to feel safe on your own is a strong move towards healthier relationships.

4. Low Self-Worth and Internalized Beliefs

People who stay in hurtful relationships often carry internalized beliefs such as:

-

“I don’t deserve better”

-

“This is the best I can get”

-

“Love always hurts”

Such beliefs might be a result of criticism experienced in the past, emotional neglect or repeated invalidation. The normalization of pain and healthy love may be strange and undeserving over time.

5. Hope for Change and the “Potential” Trap

People tend to stay in the agonizing relationships due to the fact that they are in love with whom the individual would be, rather than with whom he/she would remain to be all the time. They desperately cling to the memories of how things used to be in the start or to the few occasions when the partner takes care, is warm or understanding. In everyday life, this manifests itself as waiting until the better side of the individual comes back and that love, patience or sacrifice will one day result in an enduring change.

Mental images like the ones that state that they have not always been that way or that they will change in case one loves them sufficiently can have one emotionally involved even after being disappointed many times. With every minor change or a note of apology, hope is strengthened, although the general trend is the same.

This is psychologically reinforced by cognitive dissonance. The mind is torn between two painful truths at the same time that someone is both loved and hurting at the same time many times. The mind dwells on potential, intentions or promises in the future instead of current conduct to minimize this inner conflict. Hope is developed as a coping mechanism.

This might overtime make people become tolerant to some circumstances that they would never recommend other people to tolerate. Knowing this tendency can assist in moving the focus off of what one may be to how the relationship actually is day after day- and knowing it it tends to happen can be the first step to change.

6. Nervous System Conditioning

The nervous system of a person might become dysregulated when he/she lives in the state of chronic emotional stress and gets used to the level of tension, uncertainty, or emotional ups and downs. With time, the body gets to be on high alert. In everyday life, this can manifest itself in the form of constantly anticipating a conflict, overthinking the approach or mannerism, or being anxious when there would be nothing to be bad.

Consequently, disorder and emotional instability come to be normal and predictable, stable, steady relationships may become foreign or even dangerous. Others refer to healthy relationships as being boring not that it is not a connection, but due to the fact that a nervous system is not used to being calm.

That is why individuals might be uncomfortable in steady respectful relationships there is no adrenaline, no emotional hunt, and no necessity to remain hyper-vigilant. The body mixes passion with passion and indifference with apathy. The healing process consists of gradually reconditioning the nervous system to perceive safety, balance and emotional expression as indicators of authentic connection and not threat.

7. Social, Cultural, and Practical Pressures

Beyond internal psychology, external factors also play a role:

-

Societal expectations around marriage or commitment

-

Fear of judgment, especially for women

-

Financial dependence or shared responsibilities

-

Concern for children or family reputation

These pressures can reinforce endurance over emotional safety, making leaving feel like failure rather than self-preservation.

8. Emotional Investment and the Sunk Cost Fallacy

And the longer a relationship spans the more difficult it may be to quit. In the long run, common memories, emotional commitment, sacrifices, habits, and even a collective identity form a sense of duty. The concept of leaving can be daunting, because one learns to live in the day, routine, family ties, dreams and aspirations, and it seems that they lose a part of themselves in the process.

In this case, the sunk cost fallacy becomes influential. One might be tempted to believe that he/she has already devoted so much of his/her time, love, and effort to it, and, by departing, he/she will only render it pointless. The history of investment starts justifying the current suffering. Rather than inquiring about the healthiness of the relationship at the moment, the question is how much has been lost already.

This in real life can manifest itself in terms of staying a little more, hoping that things will get better to make the hard work worth it. Endurance is not an indicator of psychological well being. Surviving is not an indication of strength or love. The process of healing starts when individuals give themselves permission to select emotional safety and self-respect in place of the stress to make past hurt count.

Moving Toward Healing

Remaining in a painful relationship does not imply that one is weak. In more instances, it refers to the fact that they had to learn to survive on the basis of attachment, hope and perseverance. These tendencies used to make them feel secure, related or less isolated-although now they are painful. What appears as a case of staying too long to the external world is in most cases an internal struggle to defend the self emotionally.

It starts with consciousness during healing. Self-blame gives way to self-compassion when individuals see the reason why they remain. Awareness introduces the spaciousness to challenge traditional patterns and hear emotional requirements and envision relationships that are not because they are familiar but safe. Through this, change can be effected not by coercion, but through enlightenment and nurturing.

Helpful steps include:

-

Exploring attachment patterns through therapy

-

Learning nervous system regulation

-

Rebuilding self-worth and boundaries

-

Redefining love as safety, consistency, and emotional presence

Closing Thought

You do not hang about because you are mended. It remain because sometime in your life your brain and body have come to realize that love came with conditions. You were taught to adapt, wait, bear the pain, and hope, as these were the methods used to enable you to feel a part of or not so lonely. What seems to be endurance in these days was in the past a survival.

When love was forced to wait, or to keep still, or to sacrifice oneself, your system had been taught to believe that work is equal to value. You might have been taught to downplay your requirements, question your emotions, or hold that pangs are just part of intimacy. This can over time make emotional anguish, familiar to the self protection, unfamiliar or even egoistic.

Love should not be made to undermine you. It is not to get you to doubt your value, think on toes or dismiss your emotional reality. Healthy love gives you room to be safe, consistent and care about each other- it does not necessitate you to vanish and keep the relationship alive.

Making a choice is not to give up on oneself. It is not abandoning and losing love. Appreciating the fact that emotional well-being is important. It is the silent gesture of coming back to yourself after having spent years in remaining where you were not noticed. And with that decision, healing commences–not with a dramatic climax, but with an honest, sincere start.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What provokes people to remain in relationships that are harmful to them?

Since psychological aspects such as attachment styles, fear of abandonment, trauma bonding, and conditioning of the nervous system can make leaving more dangerous than remaining.

2. Does that make one weak to remain in a painful relationship?

No. It is frequently a survival mechanism that is based on previous experiences, unfulfilled emotional needs, and acquired coping mechanisms.

3. What is trauma bonding?

Trauma bonding refers to an emotional bonding derived by the presence of pain and release that the short moments of affection strengthen the attachment in spite of the harm.

4. What is the impact of childhood on relationship in adulthood?

Premature relationships form inner models of affection and protection, which affect the way proximity, discord, and emotional demands are fulfilled in adulthood.

5. How does the attachment theory contribute to unhealthy relationships?

Styles of attachment (anxious, avoidant, fearful-avoidant) influence the way individuals react to intimacy conflict, and emotional availability.

6. What is so addictive about emotional unpredictability?

Intermittent reinforcement stimulates the release of dopamine which the brain becomes preferentially conditioned to seeking relief following distress like addictive behavior.

7. What is so strong about the fear of loneliness?

The loneliness may trigger the deepest of deep-seated survival fears, in part because of the tendency to equate self-worth with being chosen or needed.

8. What is cognitive dissonance within relationships?

It is the emotional uncomfortable nature of loving someone who makes someone suffer, usually being solved by holding onto hope, or possibility as opposed to reality.

9. When do healthy relationships get boring?

The nervous system can regulate itself in a way that considers love as something intense, and calmness and consistency become strange and unsafe.

10. What is sunk cost fallacy in relationships?

One of the beliefs is that breaking away would be a waste of time and effort put in even in the case where the relationship is bad.

11. Is that the unlearnability of such patterns?

Yes. Attachment and nervous system patterns can be cured with awareness, therapy, and safe relationships.

12. Is it necessary to love someone and tolerate pain?

No. Healthy love is about emotional safety, mutual respect and consistency- not self erasure and endurance.

13. Why do individuals wish that their partner should change?

The emotional investment, early bonding and the inability to accept loss or disappointments often lead to hope.

14. Is self-selection equivalent to self-sacrifice?

No. Making a choice in favor of oneself is an expression of self-respect and recovery, but not desertion.

15. In cases where is it appropriate to seek professional assistance?

Repeated patterns are used when the emotional pain seems too great, and it is not possible to get out of the situation despite the persistent harm.

Written by Baishakhi Das

Counselor | Mental Health Practitioner

B.Sc, M.Sc, PG Diploma in Counseling

Reference

-

American Psychological Association (APA) – Relationships & Attachment

https://www.apa.org/topics/relationships -

Psychology Today – Attachment Theory

https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/basics/attachment -

Psychology Today – Trauma Bonding

https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/basics/trauma-bonding -

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) – Mental Health & Relationships

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics -

Harvard Health Publishing – Stress & the Nervous System

https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/understanding-the-stress-response -

The Gottman Institute – Healthy vs Unhealthy Relationships

https://www.gottman.com/blog/category/relationships/ -

Cleveland Clinic – Trauma Responses

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/trauma -

Mind UK – Emotional Well-being & Relationships

https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/relationships/ -

APA Dictionary of Psychology – Cognitive Dissonance

https://dictionary.apa.org/cognitive-dissonance - Why Emotionally Unavailable People Feel So Familiar

This topic performs well due to rising searches around men’s mental health, workplace stress, and burnout recovery. Combining emotional insight with practical steps increases engagement and trust.