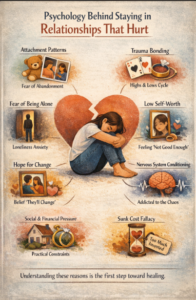

Most individuals endure aching relationships not because they love the pain but the emotional attachment seems to be strong, absorbing and almost unbreakable. The relationship can be addictive and is characterized by a feeling of longingness, hope, fear, and short moments of intimacy that continue to draw them back. And even in situations where the relationship is distressing, anxiety-inducing or self-doubting, it can become more terrifying to quit the relationship than to remain.

This contradiction that is inside creates a very perplexing question:

Is it love, or is it a trauma connection?

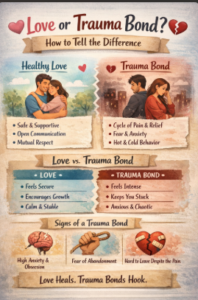

The misunderstanding comes in the fact that the bonds of trauma may also disguise as love. Severity is confused with passion, drama and drama for emotions, and bonding with belonging. The inconsistent affection, which is handed over and withheld at random, causes the nervous system to be set into action which strengthens the bond between them by creating an emotional craving instead of emotion safety.

Emotional well-being, healthy attachment, and relational healing relies on the understanding of the distinction between love and trauma bonding. Unconsciously, individuals can carry on with accustoming themselves to pain, turning a blind eye to their needs, or remain in circles that are comfortable but utterly disappointing. Understanding what is occurring under the carpet is usually the initial step towards being able to select relationships that are not only emotionally potent- but emotionally secure.

What Is Love? (From a Psychological Perspective)

New romantic love is based on emotional safety, consistency, and respect. It does not need to be afraid, to be filled with doubts or to win affection. Rather, it builds up a relational atmosphere in which the two individuals feel safe enough to be themselves and vulnerable and emotionally available. Connection is not what you need to pursue in a healthy love it is a gift given without any fee and one of the aspects that are consistently sustained.

This type of love enables the two individuals to develop, both as individuals and as a couple. Personal development does not pose a threat to the relationship but is seen as an enhancement of the relationship. Diversity is considered and needs are addressed and individuality respected instead of being smothered out.

Key features of healthy love include:

-

Emotional availability and open communication – feelings, needs, and concerns can be expressed without fear of dismissal, ridicule, or punishment.

-

Consistency in care and behavior – affection, attention, and respect are stable, not dependent on moods, power, or control.

-

Respect for boundaries – “no” is honored, autonomy is valued, and personal limits are not crossed to maintain closeness.

-

Repair after conflict – disagreements are followed by accountability, understanding, and reconnection, not prolonged withdrawal or emotional punishment.

-

Feeling calm, secure, and valued – the relationship soothes the nervous system rather than constantly activating anxiety or fear.

-

Freedom to be yourself without fear – you don’t have to shrink, perform, or abandon parts of yourself to be loved.

There is no self-abandonment that is required of healthy love to survive. You do not need to repress, endure victimization or demonstrate your value all the time. Rather, love is your emotional safe haven, where association helps to sustain you and not your identity.

What Is a Trauma Bond?

Trauma bond is developed when emotional attachment is developed based on pain and relief repetitive cycles, instead of safety and consistency. The bonds tend to occur in relationships where emotional neglect, unpredictability, or abuse is involved and where there are moments of intimacy and then withdrawal, condemnation, or emotional abuse. Gradually, the nervous system begins to connote connection with distress and reprieve with love.

Psychologically, intermittent reinforcement is the cause of trauma bonding. This is found when affection, validation or attention is provided in varying ways, at one time warm and connecting, and at other times cold and rejecting. Since there is no predictability of the reward, the brain is made as more focused on it. The bonding occurs not due to a healthy relationship but as a result of the nervous system being trapped in the process of anticipation, anxiety and temporary relief.

Passion is confused with intensity and longing with love in the trauma-bonded relationships. The peaks are euphoric and the saddens devastating-forming a strong attachment loop which is hard to lure even in situations where the relationship inflicts great emotional pain.

Common conditions where trauma bonds form include:

-

Emotionally unavailable or inconsistent partners – affection is offered unpredictably, keeping the person in a constant state of hope and anxiety.

-

Relationships involving manipulation, gaslighting, or control – reality is distorted, self-trust erodes, and dependency increases.

-

One-sided emotional labor – one person carries the responsibility for maintaining connection, repair, and emotional stability.

-

Fear of abandonment or rejection – staying feels safer than the perceived pain of being alone, even when the relationship is harmful.

-

Childhood attachment wounds replayed in adulthood – early experiences of inconsistency or neglect shape what feels familiar, even when it is painful.

Trauma bonds do not reflect weakness or inability to make a good judgment. These are survival mechanisms of adaptation that are influenced by the brain and nervous system in a kind of environment where love and pain were brought together. The healing process starts not by self-blame, but by learning and understanding that love is not supposed to hurt in order to be experienced.

Love vs Trauma Bond: Key Differences

| Love | Trauma Bond |

|---|---|

| Feels safe and steady | Feels intense and chaotic |

| Encourages growth | Keeps you stuck in survival mode |

| You feel valued | You feel anxious about losing them |

| Needs are acknowledged | Needs are minimized or ignored |

| Conflict leads to repair | Conflict leads to fear or withdrawal |

| Calm nervous system | Activated, dysregulated nervous system |

How Your Body Tells the Truth

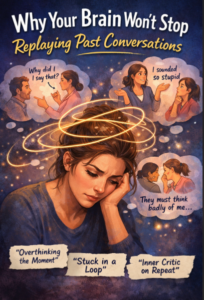

A traumatic bond can be shown by your nervous system, not just your thoughts or feelings, as one of the most evident signs as to whether you are in love or a trauma bond. The truth is something that is usually known by the body much before the mind can comprehend it.

The nervous system of a healthy love is grounded and regulated. Even in the period of conflict or emotional distress, it has a sensual feeling of security. War is not something that soothes that the relationship is at risk. You can calm yourself down, interact, and hope that the bond will be re-established. Love can be rather provoking, but it does not put you in a state of constant fear.

The body in the trauma-bonded relationships always stays alert or in survival mode. This can be accompanied by constant overthinking, hypervigilance, disposition to messages, repeating messages, or tracking tone change. The fear of leaving people is put at the forefront, and the moods are oscillated between a high level of intimacy and a strong sense of distress. The mood swings and mood busts are not indicators of passion, but indicators of imbalance in the nervous system.

The body is able to become accustomed to relating anxiety to affiliation and reprieve to affection, as time passes. It is the reason why the state of being calm may be boring or new, whereas disorder is attractive and seductive. Peace is not always love when it is uncomfortable and instability is exciting and it might be conditioning due to past attachment wounds.

Healing is about educating the nervous system that it is not dull and safe and still, but safe. And that love neither needs fear to live.

Why Trauma Bonds Feel So Strong

Trauma bonds do not indicate personal weakness, bad judgment, and emotional dependency. These are survival strategies of adaptation- the mind/ body attempt to keep connected to those environments where safety and consistency were questionable. With little or unstable care, love, or confirmation, the nervous system comes to learn clinging desperately to whatever relief can be found.

The brain starts relating short episodes of love, warmth or care with elimination of emotional suffering. These occasions serve as emotional terms of consolation, soothing troublingness to an extent that strengthens the bond. This builds a strong commitment cycle whereby the relationship is bound not by constant affection, but by the pain-temporary relief contrast.

The repeated cycle results in the relationship not being built upon any sincerity but a lack of loss, leaving, or emotional retreat. The fear rather than the safety is the cement that binds the bond together. Even in the case where the relationship is most distressing, the prospect of losing the tie may cause a lot of anxiety, grief, or even panic.

This is the reason why it is easier to keep than to leave. To remain means familiarity, predictability and partial relief whereas to leave means to experience emotional free fall. It is essential to learn about this process, not to give oneself an excuse to feel bad but to acknowledge this with the purpose to substitute self-blame with clarity. The process of healing can start when the nervous system gradually gets to know that it does not have to be injured to be connected, that safety can be achieved without hurting.

Breaking the Trauma Bond Begins with Awareness

Healing does not start with blaming yourself or the other person. It begins with recognition.

Ask yourself:

-

Do I feel more anxious than safe in this relationship?

-

Am I staying for connection—or to avoid abandonment?

-

Do I feel seen, or am I constantly trying to be enough?

Choosing emotional safety over familiarity is not giving up on love—it is returning to yourself.

Love Heals. Trauma Bonds Hook.

Love broadens out your self-image.

It promotes interest, self-confidence and emotional expression. You are more yourself in love, not smaller or quieter or less worthy but complete and less airy.

Trauma bonds on the contrary reduce the self.

They make your emotional sphere smaller; about coping with anxiety and preemptive response and maintaining connection at all costs. In the long run, your needs, voice, and identity may be marginalized to the background with survival in the limelight.

Healing is not the fast track of detaching and moving on. It is initiated by self-compassion, which refers to the realization that your to which you were attached was logical considering what you went through. The body gradually discovers a new reality, though, that safety need not be learned by pain, by means of the nervous system control, emotional intuition, and even professional help.

As this healing progresses it is possible to find what seemed magnetic to grow wearying. The anarchy that seemed like unity might become deceptive. And what used to seem strange–or even dull,–the quiet, the sameness, the tranquil existence, may gradually start to represent home.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Can love and trauma bonding coexist in the same relationship?

Yes. Love may be present in a relationship and yet traumatized. This does not necessarily imply that the bond is healthy because of the presence of a caring individual. It is whether the relationship is sustained on the basis of emotional protection and stability or fear, anxiety and intermittent reinforcement.

2. Why does a trauma bond have more strength than healthy love?

Trauma bonds balance the brain reward system together with the stress system. The uncertainty of affection heightens emotional desire such that the attachment becomes desperate and very strong. Healthy love is smoother and it may not seem exciting at first in case the nerve system is programmed to madness.

3. Can a trauma bond be dissolved without a relationship?

In other instances, recovery is possible when the relationship grows to be reliable, responsible, and responsive in the long run. Nevertheless, the length of trauma bonds might demand physical space or physical separation of the nervous system so that it re-tunes- particularly in the presence of abuse, manipulation, or chronic neglect.

4. Why am I missing the person who abused me?

Not wanting someone who hurt you does not imply you are a weak or disoriented person. The emotional and bodily brain is not the only place of storing attachment but logic. The desire is usually a depiction of unfinished attachment needs, and not the yearning to go back to hurt.

5. What is the duration of healing a trauma bond?

There is no fixed timeline. The factors that determine healing include attachment history, regulation of the nervous system, emotional support and work therapy. Consciousness and understanding are slowly reduced, and the mind becomes clearer.

6. Is it true that therapy is beneficial to trauma bonding?

Yes. Therapy, particularly attachment-informed, trauma-informed or somatic treatment, assists people to comprehend patterns, manage the nervous system, repair self-trust and create more healthy templates of relationships.

7. What are some of the signs that I am heading to healthy love?

There are indications such as being relaxed instead of anxious, being able to communicate needs without fear, confidence in consistency, and the absence of mistaking intensity and intimacy. Peace starts to get safe, not tedious.

Written by Baishakhi Das

Counselor | Mental Health Practitioner

B.Sc, M.Sc, PG Diploma in Counseling

References & Further Reading

-

American Psychological Association (APA)

https://www.apa.org

(Attachment, trauma, relationship psychology) -

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)

https://www.nimh.nih.gov

(Trauma, emotional regulation, mental health) -

Bowlby, J. (1988). A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development

(Foundational attachment theory) -

Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and Recovery

(Psychological trauma and relational impact) -

van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score

(Trauma, nervous system, and healing) -

Linehan, M. (2015). DBT Skills Training Manual

(Emotion regulation and interpersonal effectiveness) - Why You Miss People Who Hurt You

This topic performs well due to rising searches around men’s mental health, workplace stress, and burnout recovery. Combining emotional insight with practical steps increases engagement and trust.

1. The Brain Is Wired for Social Survival

1. The Brain Is Wired for Social Survival