The anxious–avoidant relationship cycle is one of the most common—and emotionally painful—patterns seen in intimate relationships. It occurs when two people with opposing attachment styles repeatedly activate each other’s deepest emotional fears. One partner seeks closeness and reassurance to feel safe, while the other seeks distance and autonomy to regulate overwhelm. This creates a recurring cycle of pursuit, withdrawal, misunderstanding, conflict, and emotional distance.

Over time, both partners feel increasingly unseen and misunderstood. The anxious partner may feel rejected or unimportant, while the avoidant partner may feel pressured or emotionally trapped. Each reaction unintentionally intensifies the other, reinforcing the cycle and making resolution feel harder with every repetition.

Importantly, this dynamic is not about lack of love or commitment. In many cases, it appears in relationships where both partners care deeply and genuinely want connection. The struggle arises because each person’s way of seeking emotional safety directly conflicts with the other’s. What feels like closeness to one feels like suffocation to the other, and what feels like space to one feels like abandonment to the other.

Without awareness, this pattern can slowly erode emotional security, trust, and intimacy. With understanding and intentional change, however, the cycle can be interrupted—allowing both partners to move toward a more balanced, emotionally safe relationship.

Understanding Attachment Styles

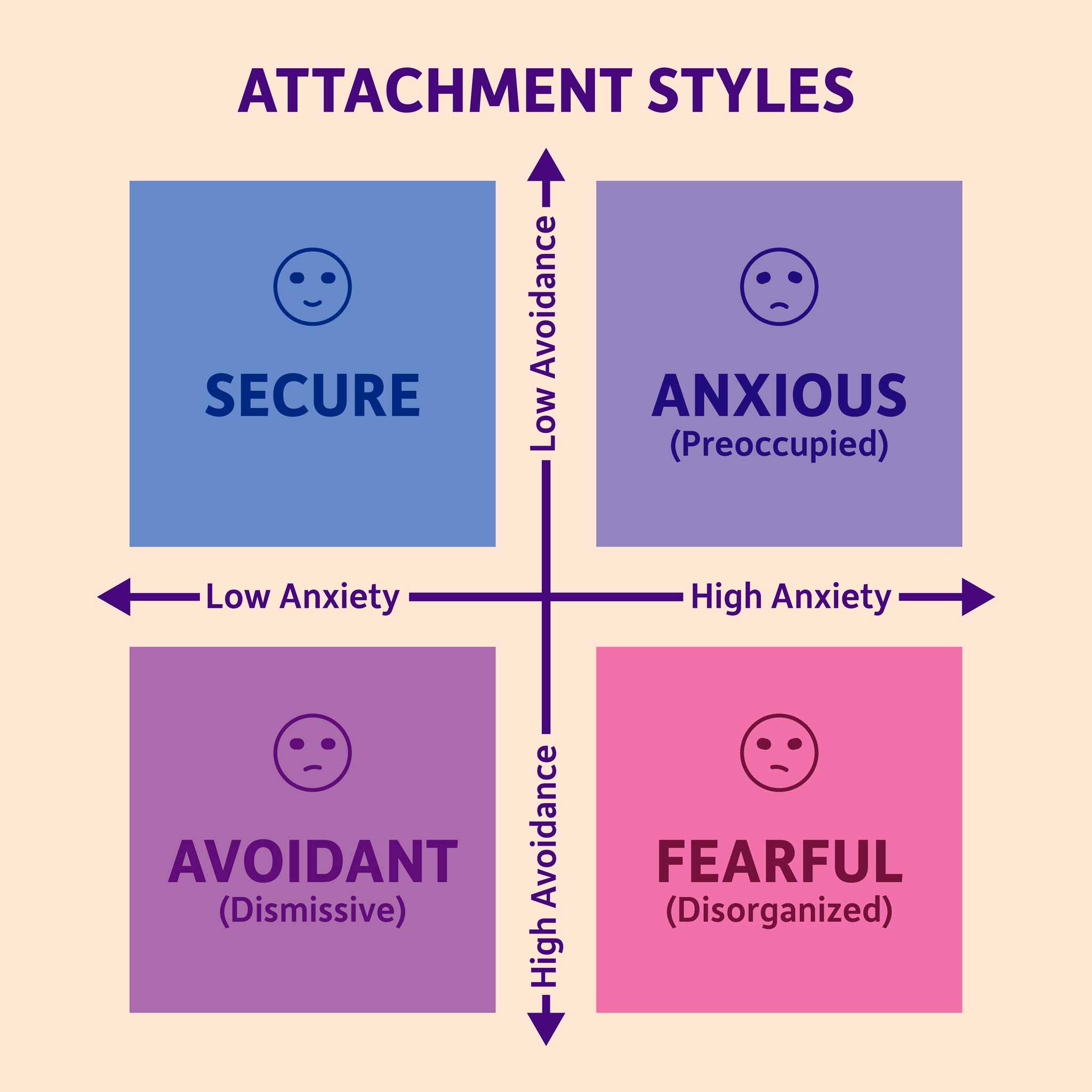

Attachment styles develop early in life based on how caregivers consistently responded to a child’s emotional needs—such as comfort, availability, responsiveness, and emotional safety. Through these early interactions, children form internal beliefs about themselves (“Am I worthy of care?”) and others (“Are people reliable and emotionally available?”). These beliefs later guide how adults approach closeness, intimacy, conflict, and emotional regulation in their relationships.

According to the American Psychological Association, attachment patterns strongly influence how individuals regulate emotions, respond to perceived threats in relationships, and seek or avoid connection in close bonds. When emotional needs feel threatened, attachment systems activate automatically—often outside conscious awareness.

The anxious–avoidant relationship cycle most commonly involves two contrasting attachment styles:

-

Anxious attachment in one partner, characterized by a heightened need for closeness, reassurance, and emotional responsiveness. This partner is highly sensitive to signs of distance or disconnection and tends to move toward the relationship during stress.

-

Avoidant attachment in the other partner, characterized by discomfort with emotional dependency and a strong need for independence and self-reliance. This partner tends to move away from emotional intensity to regulate stress.

When these two styles interact, their opposing strategies for emotional safety collide—setting the stage for the pursue–withdraw cycle that defines the anxious–avoidant dynamic.

The Anxious Partner: Fear of Abandonment

People with an anxious attachment style tend to crave closeness and reassurance. Their core fear is abandonment or emotional rejection.

Common traits include:

-

Heightened sensitivity to emotional distance

-

Strong need for reassurance

-

Overthinking messages, tone, or changes in behavior

-

Fear of being “too much” yet feeling unable to stop reaching out

When they sense distance, their nervous system activates and they move toward their partner for safety.

The Avoidant Partner: Fear of Engulfment

People with an avoidant attachment style value independence and emotional self-reliance. Their core fear is loss of autonomy or emotional overwhelm.

Common traits include:

-

Discomfort with intense emotional closeness

-

Tendency to shut down during conflict

-

Difficulty expressing vulnerability

-

Belief that needing others is unsafe or weak

When emotional demands increase, their nervous system activates and they move away to regain control and calm.

How the Anxious–Avoidant Cycle Begins

The cycle usually unfolds in predictable stages:

1. Trigger

A small event—delayed reply, distracted tone, disagreement—activates attachment fears.

-

Anxious partner feels: “I’m being abandoned.”

-

Avoidant partner feels: “I’m being pressured.”

2. Pursue–Withdraw Pattern

-

The anxious partner pursues: calls, texts, questions, emotional discussions.

-

The avoidant partner withdraws: silence, distraction, emotional shutdown.

Each reaction intensifies the other.

3. Escalation

-

Anxious partner becomes more emotional, critical, or pleading.

-

Avoidant partner becomes colder, distant, or defensive.

Both feel misunderstood and unsafe.

4. Emotional Exhaustion

The relationship enters a phase of:

-

Repeated arguments

-

Emotional numbness

-

Feeling disconnected despite being together

The cycle may temporarily stop when one partner gives up or shuts down—but it resumes when closeness returns.

Why This Cycle Feels So Addictive

Paradoxically, anxious–avoidant relationships often feel intensely magnetic, especially in the early stages. The emotional highs and lows can create a powerful sense of connection that is easily mistaken for passion or deep compatibility.

This addictive pull exists because:

-

Familiar emotional patterns feel “normal,” even when painful.

Attachment systems are shaped early in life. When a relationship recreates familiar emotional dynamics—such as chasing closeness or retreating for safety—it feels recognizable and psychologically compelling, even if it causes distress. -

Intermittent closeness reinforces hope.

Periods of emotional warmth followed by distance create a pattern similar to intermittent reinforcement. Occasional connection keeps hope alive, making partners believe that if they try harder, closeness will return and stay. -

Each partner unconsciously attempts to heal old attachment wounds through the relationship.

The anxious partner seeks reassurance that they are lovable and won’t be abandoned. The avoidant partner seeks closeness without feeling overwhelmed or losing autonomy. Both are trying to resolve unmet emotional needs—without realizing they are repeating the same pattern.

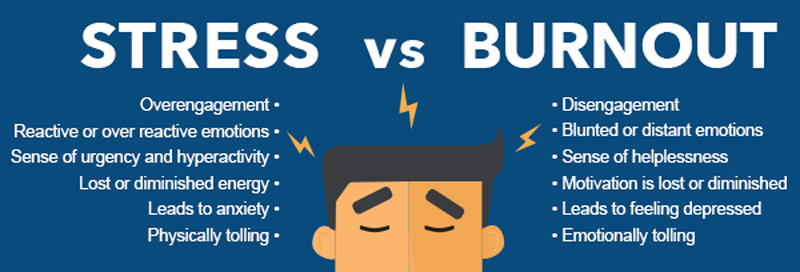

Without awareness and conscious change, this cycle slowly becomes emotionally exhausting and unstable. What once felt exciting begins to feel confusing, draining, and unsafe, increasing anxiety, withdrawal, and relational burnout rather than intimacy.

Psychological Impact of the Cycle

Over time, the anxious–avoidant cycle takes a significant psychological toll on both partners. Because emotional needs are repeatedly unmet, the relationship begins to feel unsafe, unpredictable, and exhausting.

This pattern can lead to:

-

Chronic anxiety or emotional numbness

The anxious partner may remain in a constant state of worry, hypervigilance, and fear of abandonment, while the avoidant partner may cope by shutting down emotionally, leading to numbness and detachment. -

Low self-esteem and self-blame

Both partners often internalize the conflict. The anxious partner may believe they are “too much,” while the avoidant partner may see themselves as emotionally inadequate or incapable of closeness. -

Increased conflict and misunderstanding

Conversations become reactive rather than constructive. Small issues escalate quickly because attachment fears—not the present problem—are driving the interaction. -

Emotional burnout within the relationship

Repeated cycles of hope, disappointment, and disconnection drain emotional energy, leaving both partners feeling tired, resentful, or disengaged.

Many couples interpret these struggles as fundamental incompatibility or lack of love. In reality, the distress is often the result of unresolved attachment wounds being activated and replayed within the relationship. With awareness and support, this pattern can be understood—and interrupted—before it causes lasting emotional damage.

How to Break the Anxious–Avoidant Cycle

Breaking the cycle requires awareness, emotional regulation, and new relational skills.

1. Name the Pattern

Recognizing “We are in the pursue–withdraw cycle” reduces blame and increases insight.

2. Regulate Before Communicating

Attachment reactions are nervous-system responses. Pausing, grounding, and calming the body is essential before discussion.

3. Practice Secure Behaviors

-

Anxious partner: Practice self-soothing and tolerating space

-

Avoidant partner: Practice staying emotionally present during discomfort

Security is built through behavior, not intention.

4. Use Clear, Non-Blaming Language

Replace accusations with needs:

-

“I feel anxious when we disconnect; reassurance helps me.”

-

“I feel overwhelmed when emotions escalate; I need calm communication.”

5. Seek Professional Support

Attachment-based therapy or couples counseling can help both partners:

-

Understand their attachment wounds

-

Develop emotional safety

-

Break unconscious patterns

Final Reflection

The anxious–avoidant cycle is not about one partner being “needy” and the other being “cold.”

It is about two nervous systems responding to threat and seeking safety in opposite ways—one through closeness, the other through distance.

When these protective strategies collide, both partners suffer, even though both are trying to preserve the relationship in the only way they know how.

With awareness, patience, and the right support, this cycle does not have to define the relationship. As partners learn to recognize their attachment patterns, regulate emotional responses, and communicate needs safely, the dynamic can soften—and in many cases, transform into a more secure, stable, and emotionally safe connection.

Healing begins not with blame, but with understanding.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is the anxious–avoidant relationship cycle?

The anxious–avoidant cycle is a recurring relationship pattern where one partner seeks closeness and reassurance (anxious attachment), while the other seeks distance and emotional space (avoidant attachment). Each partner’s coping strategy unintentionally triggers the other’s deepest emotional fears, leading to repeated conflict and disconnection.

2. Does this cycle mean the relationship is unhealthy or doomed?

Not necessarily. The presence of this cycle does not mean a lack of love or compatibility. It often reflects unresolved attachment wounds rather than conscious choices. With awareness, emotional regulation, and support, many couples are able to soften or break the cycle.

3. Why does the anxious partner keep pursuing?

The anxious partner’s nervous system is highly sensitive to emotional distance. Pursuing closeness, reassurance, or communication is an unconscious attempt to restore emotional safety and reduce fear of abandonment.

4. Why does the avoidant partner withdraw?

The avoidant partner experiences intense emotional closeness as overwhelming or threatening. Withdrawing helps them regulate stress, regain a sense of control, and protect their autonomy—even though it may unintentionally hurt their partner.

5. Can two people with these attachment styles have a healthy relationship?

Yes. Healing is possible when both partners:

-

Recognize the pattern

-

Take responsibility for their emotional responses

-

Practice secure behaviors

-

Learn to communicate needs without blame

Professional support often helps accelerate this process.

6. Is the anxious–avoidant cycle related to childhood experiences?

Yes. Attachment styles typically develop in early childhood based on caregiver responsiveness and emotional availability. These early experiences shape how adults approach intimacy, conflict, and emotional safety in relationships.

7. When should couples seek professional help?

Couples should consider therapy when:

-

The same conflicts repeat without resolution

-

Emotional distance or anxiety keeps increasing

-

Communication feels unsafe or reactive

-

One or both partners feel emotionally exhausted

Attachment-based or couples therapy can help identify patterns and create healthier relational dynamics.

Written by Baishakhi Das

Counselor | Mental Health Practitioner

Qualifications: B.Sc in Psychology | M.Sc | PG Diploma in Counseling

Reference

-

American Psychological Association

Attachment and close relationships

https://www.apa.org/monitor/julaug09/attachment -

Bowlby, J. (1988).

A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development.

https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1988-97390-000 -

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. R. (1987).

Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1987-28436-001 -

Johnson, S. M. (2019).

Attachment Theory in Practice: Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT).

https://www.guilford.com/books/Attachment-Theory-in-Practice/Susan-Johnson/9781462538249 -

Levine, A., & Heller, R. (2010).

Attached: The New Science of Adult Attachment.

https://www.attachedthebook.com - Emotional Burnout: Symptoms You Shouldn’t Ignore