A Deep Psychological Explanation with Clinical Insight

Attachment styles shape how we love, connect, fight, withdraw, cling, trust, and fear loss in adult relationships. Many relationship struggles are not about incompatibility—but about attachment wounds replaying themselves in adulthood.

Rooted in attachment theory, developed by John Bowlby and expanded by Mary Ainsworth, this framework explains how early emotional bonds become internal working models that guide adult intimacy.

This article explores attachment styles in depth, with a modern, relational, and counseling-oriented lens.

What Is Attachment Theory?

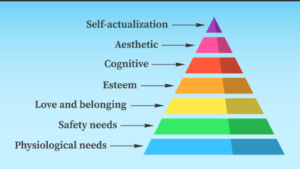

Attachment theory proposes that human beings are biologically wired for connection. From birth, survival depends not only on food and shelter, but on emotional closeness, protection, and responsiveness from significant others—primarily caregivers in early life.

According to attachment theory, children are constantly (and unconsciously) asking three fundamental questions through their experiences with caregivers:

-

Am I lovable and worthy of care?

-

Are others reliable and emotionally available?

-

Is closeness safe, or does it lead to pain, rejection, or loss?

The answers to these questions are not learned through words—but through repeated emotional experiences.

How Attachment Beliefs Form in Childhood

When caregivers are:

-

Emotionally responsive

-

Consistent

-

Attuned to distress

the child learns that:

-

Their needs matter

-

Emotions are safe to express

-

Relationships provide comfort

When caregivers are:

-

Inconsistent

-

Emotionally unavailable

-

Dismissive, frightening, or unpredictable

the child adapts by developing protective strategies—such as clinging, suppressing needs, or staying hyper-alert to rejection.

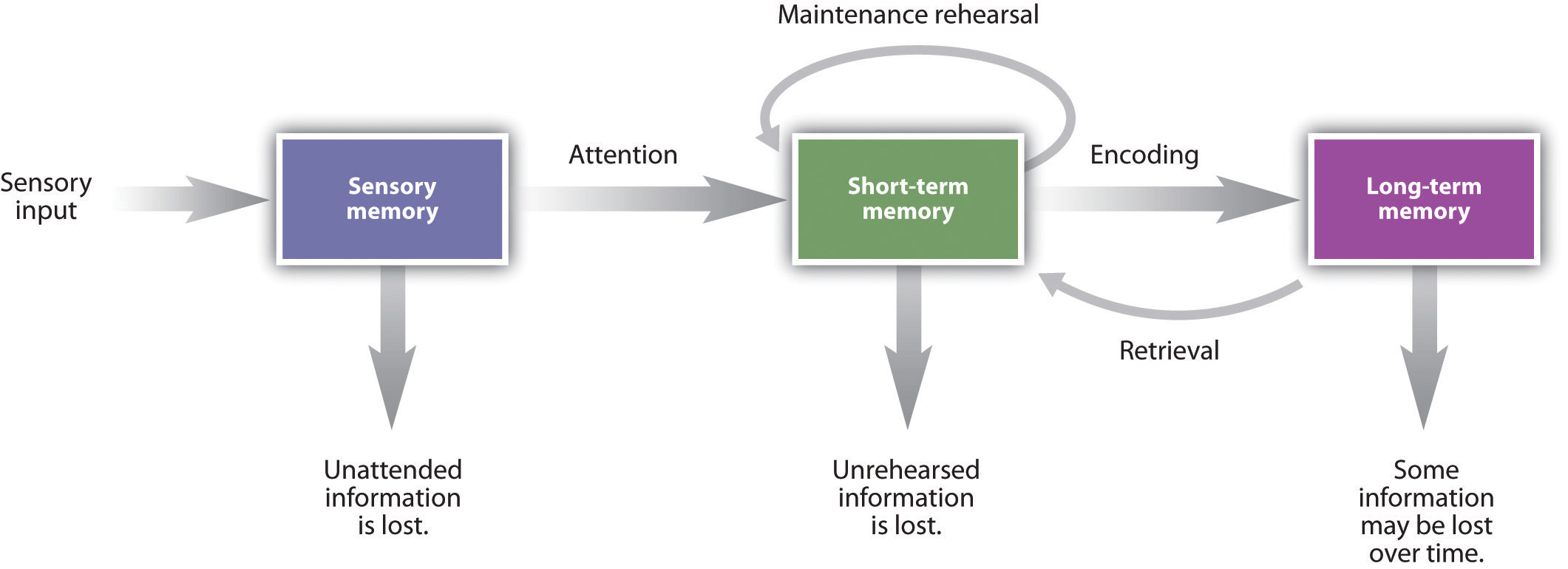

These adaptations are not conscious choices. They are nervous-system-level learning meant to preserve connection and survival.

Internal Working Models: The Emotional Blueprint

Over time, these early experiences form what attachment theory calls internal working models—deeply ingrained emotional templates about:

-

The self (“Who am I in relationships?”)

-

Others (“What can I expect from people?”)

-

Intimacy (“What happens when I get close?”)

These models operate automatically and shape:

-

Emotional reactions

-

Relationship expectations

-

Conflict behavior

-

Fear of abandonment or intimacy

Attachment Styles in Adulthood

As individuals grow, attachment needs do not disappear—they shift from caregivers to romantic partners, close friends, and significant relationships.

In adulthood, attachment styles become most visible when:

-

There is emotional vulnerability

-

Conflict arises

-

Distance, rejection, or loss is perceived

-

Commitment deepens

This is why romantic relationships often feel so intense—they activate early attachment memories, not just present-day experiences.

A Crucial Clarification

Attachment styles are adaptive, not pathological.

They reflect how a person learned to survive emotionally in their earliest relationships.

What once protected the child may later:

-

Create anxiety

-

Cause emotional distance

-

Lead to repeated relationship patterns

But because attachment is learned, it can also be relearned and healed—through awareness, safe relationships, and therapeutic work.

Key Insight

Attachment theory reminds us that:

Adult relationship struggles are often not about the present partner—

but about old emotional questions still seeking safer answers.

Understanding attachment theory is the first step toward breaking unconscious patterns and building emotionally secure relationships.

The Four Main Attachment Styles in Adults

Secure attachment

This style is characterized by a deep sense of inner safety in relationships. Adults with secure attachment hold the belief that they are worthy of love, that others are generally reliable, and that emotional closeness is safe rather than threatening. This style typically develops when caregivers in childhood were emotionally responsive, consistent, and available during moments of distress.

As a result, the nervous system learns to expect comfort rather than rejection in close relationships. In adulthood, securely attached individuals are comfortable with both intimacy and independence. They communicate their needs openly, regulate emotions effectively during conflict, and are able to give and receive support without losing their sense of self. One of the strongest psychological strengths of secure attachment is the ability to repair after conflict—disagreements do not threaten the bond, but are experienced as manageable and temporary.

Anxious (preoccupied) attachment

This style develops when early caregiving was inconsistent or emotionally unpredictable—sometimes nurturing, sometimes unavailable. The child learns that love is uncertain and must be closely monitored. As adults, individuals with anxious attachment often believe they may be abandoned and that reassurance is necessary to feel safe. Closeness becomes strongly associated with security, which can lead to heightened emotional sensitivity.

In relationships, this shows up as fear of abandonment, overthinking messages or tone, and a constant need for reassurance. Self-soothing is difficult, so emotional regulation often depends on the partner’s responses. Common behaviors include clinging, people-pleasing, and emotional protest such as crying, anger, or threats of leaving. Internally, anxiously attached adults often feel “too much,” emotionally dependent, and chronically insecure—even when they are loved and cared for.

Avoidant (dismissive) attachment

This style is shaped by childhood environments where caregivers were emotionally distant, dismissive of feelings, or overly critical and demanding. In such settings, the child learns that expressing needs leads to rejection or disappointment, and that self-sufficiency is the safest strategy.

Adults with avoidant attachment tend to believe they can only rely on themselves, that needing others is risky, and that closeness threatens autonomy or control. In relationships, they often feel uncomfortable with emotional intimacy and struggle to express vulnerability. They value independence highly, withdraw during conflict, and may shut down emotionally when situations become intense. Common patterns include emotional distancing, avoiding difficult conversations, minimizing personal needs, or ending relationships when intimacy deepens. Although they may appear confident and self-reliant, avoidantly attached individuals often feel overwhelmed by emotions, fearful of dependence, and uncomfortable when others rely on them.

Fearful-avoidant (disorganized) attachment

It reflects a profound inner conflict around closeness. It often develops in the context of childhood trauma, abuse, neglect, or caregiving that was both comforting and frightening. In these early experiences, the child learns that the source of safety is also a source of fear, creating deep confusion.

Adults with fearful-avoidant attachment hold contradictory beliefs: they long for closeness but experience it as dangerous, associate love with pain, and struggle to know whom to trust. In relationships, this results in intense attraction followed by sudden withdrawal, push–pull dynamics, and difficulty trusting even loving partners. Emotional volatility is common. Behaviors may include sudden shutdowns, self-sabotage, and simultaneous fear of intimacy and abandonment. Internally, these individuals experience a powerful longing for connection mixed with fear, shame, and confusion, making relationships feel both deeply desired and deeply threatening.

Together, these attachment styles explain why people respond so differently to intimacy, conflict, and emotional closeness in adult relationships—and why many relationship struggles are rooted not in the present, but in early emotional learning.

Attachment Styles in Relationship Dynamics

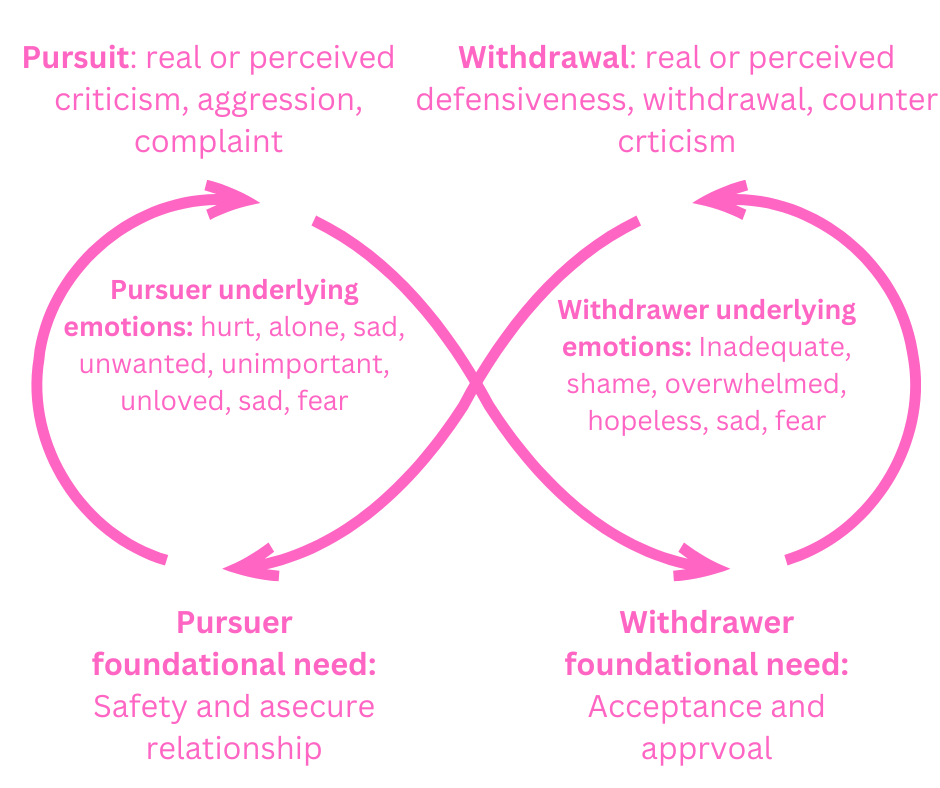

Anxious + Avoidant: The Pursue–Withdraw Cycle

-

Anxious partner seeks closeness

-

Avoidant partner withdraws

-

Anxiety increases → pursuit intensifies

-

Avoidance deepens → distance grows

This cycle feels intense and addictive—but is emotionally exhausting.

Secure + Insecure

Secure partners can offer co-regulation, but only if boundaries and awareness exist.

Attachment Styles and Mental Health

Unresolved attachment wounds often manifest as:

-

Anxiety disorders

-

Depression

-

Trauma responses

-

Emotional dysregulation

-

Codependency

-

Fear of intimacy or abandonment

Many relationship conflicts are attachment triggers, not actual relationship problems.

Can Attachment Styles Change?

Yes. Attachment styles are learned—and therefore modifiable.

Healing occurs through:

-

Emotionally safe relationships

-

Therapy (especially attachment-informed or trauma-informed)

-

Developing self-awareness

-

Learning emotional regulation

-

Corrective relational experiences

Earned secure attachment is possible—even after trauma.

Attachment Styles in Counseling Practice

In therapy, attachment work involves:

-

Identifying attachment patterns

-

Understanding emotional triggers

-

Regulating the nervous system

-

Reworking internal working models

-

Practicing safe emotional expression

The therapeutic relationship itself often becomes the first secure base.

Key Takeaway

Attachment styles explain why love can feel safe, overwhelming, distant, or terrifying.

Relationships don’t trigger us randomly.

They activate old attachment memories asking to be healed.

Understanding your attachment style is not about blame—it is about awareness, compassion, and change.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What are attachment styles in adult relationships?

Attachment styles are patterns of emotional bonding formed in early childhood that influence how adults experience intimacy, trust, conflict, and emotional closeness in relationships.

2. Can attachment styles change in adulthood?

Yes. Attachment styles are learned patterns, not fixed traits. Through self-awareness, emotionally safe relationships, and therapy, individuals can develop earned secure attachment.

3. What is the most common attachment style?

Secure attachment is the healthiest but not always the most common. Many adults show anxious, avoidant, or fearful-avoidant patterns due to early relational experiences.

4. Why do anxious and avoidant partners attract each other?

Anxious and avoidant styles often form a pursue–withdraw cycle, where one seeks closeness and the other seeks distance. The pattern feels familiar at a nervous-system level, even when it is distressing.

5. How do attachment styles affect conflict in relationships?

Attachment styles shape how people respond to threat:

-

Anxious styles intensify emotions to regain closeness

-

Avoidant styles withdraw to regain control

-

Secure styles seek repair and communication

6. Is attachment theory only about romantic relationships?

No. While attachment styles are most visible in romantic relationships, they also influence friendships, family dynamics, parenting, and even therapeutic relationships.

7. How does therapy help with attachment issues?

Therapy provides a secure relational space where clients can explore emotions, regulate the nervous system, and revise internal working models through corrective emotional experiences.

Written by Baishakhi Das

Counselor | Mental Health Practitioner

B.Sc, M.Sc, PG Diploma in Counseling

Reference

-

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss: Vol. 1. Basic Books

https://www.simplypsychology.org/attachment.html -

Ainsworth, M. et al. (1978). Patterns of Attachment. Lawrence Erlbaum

https://www.simplypsychology.org/mary-ainsworth.html -

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2016). Attachment in Adulthood. Guilford Press

-

American Psychological Association – Attachment & Relationships

https://www.apa.org -

National Institute of Mental Health – Relationships and Mental Health

https://www.nimh.nih.gov - Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs in Modern Life: