Overthinking is not loud.

It doesn’t crash into life like a hurricane; it slips in quietly, like a whisper in the dark.

No one notices its arrival — not even the person suffering from it.

It begins innocently.

A single thought, gentle and harmless:

“What if I’m wrong?”

Then a second thought follows:

“What if something goes wrong?”

And before the heart even realizes what’s happening, the mind has already constructed a thousand possibilities — most of them painful, unlikely, or terrifying.

This is the tragedy of overthinking:

It doesn’t attack suddenly.

It slowly convinces the mind that danger is everywhere.

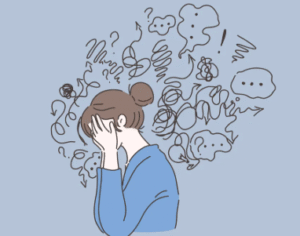

🧠 The Inner Experience of an Overthinker

Many overthinkers explain their internal world with heartbreaking simplicity:

“I can’t switch off my brain.”

“I feel exhausted even while doing nothing.”

“I replay the same memory again and again.”

“Even the smallest decisions feel dangerous.”

These aren’t exaggerations.

They reflect a mind stuck in hyper-vigilance — constantly predicting, rehearsing, evaluating, and worrying.

To the outside world, the overthinker appears:

- Calm

- Responsible

- Mature

- Polite

- Strong

But inside, a different reality exists:

- A constant fear of failure

- Excessive self-criticism

- Anxiety about disappointing others

- Difficulty forgiving oneself

- Feeling unsafe even in normal situations

The world sees composure.

The mind experiences chaos.

And that chaos is silent — which is why most people never notice.

🌪️ When the Brain Becomes a Storm

The human brain is wired for survival.

It tries to protect us by predicting danger — sometimes too much.

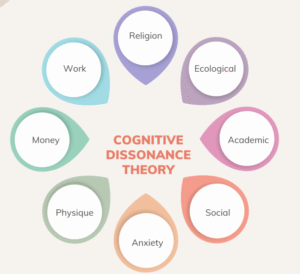

In an overthinking mind, the amygdala (fear center) works overtime, while the prefrontal cortex (logic and calm reasoning) becomes tired.

So even tiny decisions feel life-threatening:

- “Should I text them or wait?”

- “Did I say something wrong earlier?”

- “What if I make a mistake at work tomorrow?”

Overthinking turns possibilities into threats.

It turns:

- Hope → Fear

- Dreams → Pressure

- Love → Self-doubt

No matter how safe the world is outside, the brain keeps sending danger alarms.

That is why an overthinker is tired even without doing anything.

Their body rests.

Their brain never does.

🧡 A Silent Storm No One Sees

Overthinking does not ruin life dramatically; it slowly steals the joy of living.

- You laugh, but not freely.

- You relax, but not fully.

- You love, but fear losing.

- You try, but doubt every step.

People applaud your responsibility, your maturity, your perfectionism —

not knowing that each of these is powered by fear, not comfort.

No one hears the overthinking person crying inside because overthinking is silent.

And silence is the hardest suffering to explain.

🌻 But Here Is the Truth the Overthinker Needs to Hear

Overthinking does not mean you are weak.

It means:

- You care deeply.

- You feel intensely.

- You imagine multiple outcomes because your brain is fast and intelligent.

- You replay memories because they matter to you.

- You prepare for the worst because you’ve been hurt before.

Your mind is not broken.

It is overprotective.

And an overprotective mind can learn to feel safe again.

🍂 The Mind that Wants to Keep You Safe

Overthinking is not a weakness.

It is a self-protection reflex.

If you could hear the real message hidden underneath overthinking, it would be something like:

“I’m trying to keep you safe. I don’t want you to get hurt again.”

The mind isn’t trying to destroy you.

It’s trying to protect the heart that has been hurt before.

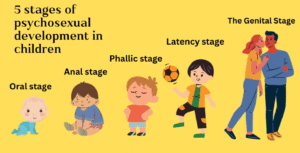

🕊️ A Story That Lives Inside Many of Us

A young woman once said during therapy:

“I don’t overthink because I love drama. I overthink because I’m scared that something good may be taken away from me.”

Her fear didn’t come from the present.

It came from a memory the heart still remembered.

And that is the secret of overthinking:

It is rarely about the situation happening in front of you —

It is about the pain behind you that you never want to feel again.

🌧️ The Damage No One Notices

Overthinking slowly steals:

- Confidence

- Peace

- Sleep

- Decision-making ability

- Joy

- Motivation

The more you think, the less you trust yourself.

The less you trust yourself, the more you think.

Not because you are weak —

but because your brain has learned that thinking feels safer than living.

💫 The Human Behind the Habit

People who overthink are usually:

- Sensitive

- Empathetic

- Emotionally deep

- Afraid of hurting others

- Afraid of being misunderstood

- Afraid of making a mistake

Overthinking doesn’t happen because a person doesn’t care.

It happens because they care too deeply.

The world benefits from their compassion —

but inside, they carry a battle no one sees.

✍️ Reflection Journal — for this section

Write slowly. Let emotions breathe.

- When does my overthinking get louder?

- Do I get afraid more when I want something deeply?

- If my overthinking voice was protecting me, what would it say?

Then write this sentence from the heart:

“My overthinking does not make me broken — it makes me someone who has felt deeply and loved deeply.”

🔥 The Storm Inside the Brain — When the Mind Fights Itself

People often say, “Stop thinking so much.”

But if the brain could stop, it would.

Overthinking isn’t a choice — it is a neurological storm.

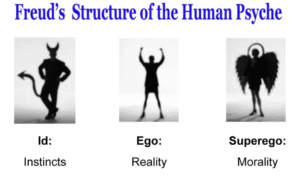

Inside the brain of an overthinker, two forces are constantly at war:

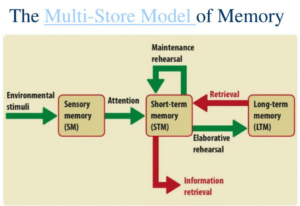

| Part of the Brain | Role | Behavior in Overthinking |

| Amygdala | Emotional alarm system | Detects danger — even when there is none |

| Prefrontal Cortex | Logical decision-maker | Thinks, analyzes, plans, predicts — excessively |

When the amygdala senses emotional risk — rejection, failure, judgement, loss — it sends a message:

“Alert! We’re not safe!”

The prefrontal cortex responds:

“Let me analyze every possibility so we don’t get hurt.”

And the storm begins.

🌪️ The Loop of Survival Thinking

When fear is triggered, the brain releases cortisol and adrenaline — stress hormones.

They give energy for survival — but they also trap the mind in repetition.

The loop looks like this:

Fear ➝ Stress hormones ➝ More thoughts ➝ More fear ➝ Even more thoughts

This is why overthinking feels uncontrollable.

The brain is not “stubborn” — it is overprotective.

⚡ Why the Brain Exaggerates Negatives

From an evolutionary perspective, humans survived by detecting threats early.

The brain remembers negative experiences more strongly than positive ones.

Psychologists call this:

🧠 The Negativity Bias

So the brain is more sensitive to:

- Rejection than acceptance

- Criticism than appreciation

- The risk of failure than the joy of success

Overthinkers are not pessimistic —

their brain is trained to prevent emotional damage.

🌪️ Why Sleep Doesn’t Fix It

An overthinker can be lying in bed, tired, eyes closed, yet the mind is wide awake.

Because the brain behaves like this:

The body sleeps → but the amygdala is still on guard

The brain wants rest → but the heart feels unsafe

The brain cannot rest in danger — even emotional danger.

💥 The Inner Civil War

One part of the mind says:

“I want to take chances, live freely.”

Another part says:

“No — stay safe. Don’t risk pain.”

This inner conflict causes:

- Head pressure

- Tight chest

- Stomach discomfort

- Restlessness

- Emotional numbness

The storm is not outside —

it is inside the mind, invisible yet exhausting.

💔 A Story Many Will Recognize

Arjun was deeply in love, yet he always feared losing the girl he loved.

Every time she was busy, every time she replied late, every time her tone changed slightly…

his brain panicked.

Not because she did anything wrong —

but because his brain remembered the pain of losing someone before.

His fear was not built on the present —

it was built on memory.

That is the essence of overthinking:

The brain remembers pain longer than happiness.

⚜️ Cognitive Science Insight

Individuals who overthink show higher activity in the Default Mode Network (DMN) — the part of the brain active during:

- Self-evaluation

- Memory recall

- Imagination

- Future predictions

So overthinkers are not broken.

They are highly analytical and self-aware — only in overdrive.

The same brain that causes overthinking can:

- Love deeply

- Care deeply

- Plan deeply

- Create deeply

- Feel deeply

The mind does not need silencing —

it needs reassurance and calmness.

✍️ Brain–Body Reflection Worksheet

Take a moment and write:

- My emotional triggers

- I feel mentally unsafe when ______

- My physical signals of overthinking

- My body reacts like this when I overthink ______

- My self-protective belief

- My brain is trying to protect me from ______

Then write this message to your brain:

“Thank you for trying to protect me. We are not in danger anymore.”

This single sentence begins healing more than self-criticism ever will.

🌿 Gentle Closure of This Section

There is nothing wrong with your brain.

It is not defective — it is over alert.

It is not trying to destroy your peace —

it is trying to preserve your safety.

The storm inside the brain is not a flaw.

It is a story of survival.

💭 “The problem isn’t thinking too much — it’s believing every thought is a threat.”