Personality does not develop in isolation. From the earliest moments of life, a child’s emotional world, beliefs, coping patterns, and sense of self are shaped through relationships—especially the relationship with parents or primary caregivers. Parenting styles play a crucial role in how children learn to trust, regulate emotions, relate to others, and view themselves.

This article explores how different parenting styles influence personality development, drawing from developmental psychology, attachment theory, and real-life behavioral patterns. As a mental health professional, you may notice these patterns daily—in children, adolescents, and even adults reflecting their early family experiences.

Understanding Parenting Styles: A Psychological Framework

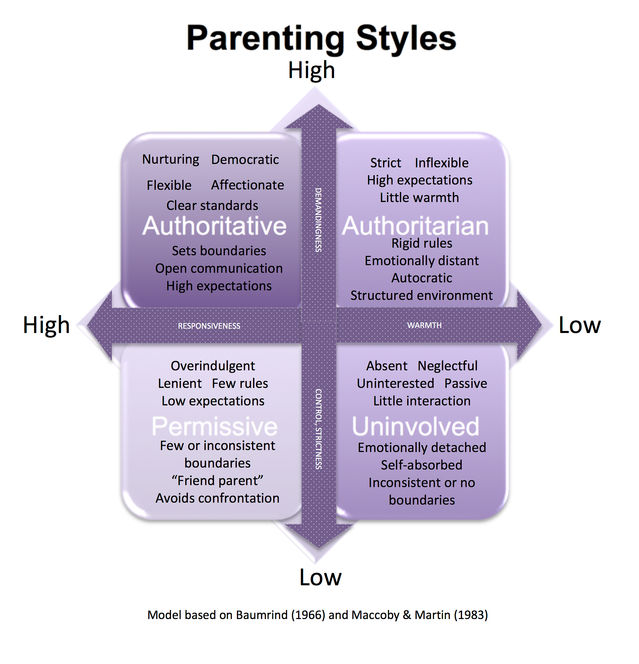

The concept of parenting styles was systematically introduced by Diana Baumrind, who identified consistent patterns in how parents interact with their children. Later researchers expanded her work, but the core idea remains: parenting style reflects emotional climate, discipline methods, communication patterns, and expectations.

Parenting styles are generally classified into four main types:

-

Authoritative

-

Authoritarian

-

Permissive

-

Neglectful (Uninvolved)

Each style affects personality traits such as self-esteem, emotional regulation, independence, resilience, empathy, and interpersonal functioning.

Why Personality Development Is Sensitive to Parenting

Personality development is especially sensitive to parenting because the child’s brain, emotions, and sense of self are still under construction. In early life, children do not yet have the neurological capacity or psychological independence to regulate emotions, interpret experiences, or assign meaning on their own. Parents and primary caregivers therefore become the first emotional regulators, mirrors, and interpreters of the world.

Personality development involves several core psychological domains:

1. Emotional Regulation

Children are not born knowing how to calm themselves, manage anger, or tolerate frustration. They learn emotional regulation through co-regulation—when caregivers respond consistently to their emotional needs.

-

When parents soothe distress, label emotions, and model calm responses, children gradually internalize these skills.

-

When emotions are ignored, punished, or mocked, children may suppress feelings or become emotionally reactive.

Over time, these early experiences shape whether a person grows up emotionally resilient or emotionally dysregulated.

2. Self-Concept and Self-Worth

A child’s sense of “Who am I?” develops largely through parental responses.

-

When caregivers show acceptance, interest, and validation, children develop healthy self-worth.

-

When love feels conditional—based on obedience, achievement, or silence—children may internalize beliefs such as “I am not enough” or “I must earn love.”

These early self-beliefs often persist into adulthood, influencing confidence, perfectionism, people-pleasing, or self-criticism.

3. Social Competence

Parents are a child’s first social world. Through everyday interactions—play, conflict, affection, discipline—children learn:

-

How to communicate needs

-

How to handle disagreements

-

Whether relationships feel safe or threatening

Supportive parenting helps children develop empathy, cooperation, and assertiveness. In contrast, harsh or inconsistent parenting may lead to aggression, withdrawal, or fear of social judgment.

4. Coping Mechanisms

How parents respond to stress teaches children how to cope with challenges.

-

Emotionally available parents model problem-solving, flexibility, and help-seeking.

-

Emotionally unavailable or critical parents may unintentionally teach avoidance, emotional shutdown, aggression, or over-control.

These coping styles later show up in how adults handle failure, rejection, pressure, and loss.

5. Moral Reasoning

Children initially understand right and wrong not as abstract concepts, but through relationships.

-

When parents explain rules with empathy and reasoning, children develop internal moral values.

-

When discipline is based solely on fear or punishment, morality remains external—driven by avoidance rather than understanding.

This influences whether adults act from personal values or from fear of consequences and authority.

6. Attachment Patterns

Perhaps the most powerful influence of parenting is on attachment. According to John Bowlby, repeated interactions with caregivers form internal working models—deep mental and emotional templates about:

-

Whether others are trustworthy

-

Whether emotions will be met with care or rejection

-

Whether closeness is safe or risky

These internal working models guide how individuals later relate to:

-

Authority figures

-

Romantic partners

-

Conflict and criticism

-

Emotional intimacy and stress

Because these models develop before conscious memory, they often feel like “just the way I am”, even though they are learned patterns.

Why Early Parenting Has Long-Term Impact

Children are neurologically and emotionally dependent on caregivers. Their brains are highly plastic, meaning repeated emotional experiences literally shape neural pathways. What is experienced repeatedly becomes familiar, automatic, and internalized.

This is why:

-

Consistent emotional safety fosters secure, adaptable personalities

-

Chronic emotional neglect or fear can lead to anxiety, avoidance, or emotional numbness

Personality, then, is not simply a trait—it is the emotional memory of early relationships.

1. Authoritative Parenting: The Foundation of Psychological Health

Core Characteristics

-

High warmth and responsiveness

-

Clear rules and consistent boundaries

-

Open communication

-

Encouragement of independence

-

Discipline through reasoning, not fear

Impact on Personality Development

Children raised with authoritative parenting tend to develop:

-

Secure self-esteem – They feel valued and competent

-

Emotional intelligence – Emotions are acknowledged, not dismissed

-

Self-discipline – Internal regulation rather than fear-based compliance

-

Social confidence – Comfort in relationships and teamwork

-

Resilience – Ability to cope with failure and stress

Psychologically, this style supports secure attachment, allowing children to explore the world while knowing emotional support is available.

Adult Personality Outcomes

-

Balanced confidence

-

Healthy boundaries

-

Emotional expressiveness

-

Adaptive coping strategies

-

Stable relationships

Authoritative parenting is consistently associated with the most positive personality outcomes across cultures.

2. Authoritarian Parenting: Obedience Over Emotional Growth

Core Characteristics

-

High control, low warmth

-

Strict rules with little explanation

-

Emphasis on obedience and authority

-

Punitive discipline

-

Limited emotional expression

Impact on Personality Development

Children raised in authoritarian environments often develop:

-

Low self-esteem – Love feels conditional

-

Fear-based compliance – Behavior driven by punishment avoidance

-

Poor emotional expression – Feelings are suppressed

-

High anxiety or anger – Emotional needs remain unmet

-

External locus of control – Reliance on authority for validation

Emotionally, children may learn that mistakes equal rejection, leading to perfectionism or rebellion.

Adult Personality Outcomes

-

Difficulty expressing emotions

-

Fear of authority or excessive submission

-

Rigid thinking patterns

-

High stress sensitivity

-

Relationship difficulties

While such children may appear “disciplined,” internally they often struggle with emotional insecurity.

3. Permissive Parenting: Freedom Without Structure

Core Characteristics

-

High warmth, low control

-

Few rules or inconsistent boundaries

-

Avoidance of conflict

-

Overindulgence

-

Child-led decision-making

Impact on Personality Development

Children raised under permissive parenting may develop:

-

Poor impulse control – Difficulty delaying gratification

-

Entitlement – Expectation that needs come first

-

Low frustration tolerance – Struggle with limits

-

Insecurity – Lack of structure creates emotional instability

-

Weak self-discipline – External regulation is missing

Though emotionally expressive, these children often feel unsafe due to unclear expectations.

Adult Personality Outcomes

-

Difficulty with responsibility

-

Struggles with authority and rules

-

Emotional impulsivity

-

Relationship instability

-

Poor stress tolerance

Warmth alone, without boundaries, does not foster emotional maturity.

4. Neglectful (Uninvolved) Parenting: Emotional Absence

Core Characteristics

-

Low warmth, low control

-

Emotional unavailability

-

Minimal involvement

-

Basic needs met, emotional needs ignored

-

Parent preoccupied with personal issues

Impact on Personality Development

This style has the most damaging psychological effects. Children often develop:

-

Low self-worth – Feeling unimportant or invisible

-

Emotional numbness or dysregulation

-

Attachment difficulties – Fear of closeness or abandonment

-

Poor social skills

-

High risk of depression and anxiety

Without emotional mirroring, children struggle to understand themselves.

Adult Personality Outcomes

-

Chronic emptiness

-

Avoidant or anxious attachment

-

Difficulty trusting others

-

Emotional detachment

-

Vulnerability to addiction or maladaptive coping

Emotional neglect is often invisible—but its psychological impact is profound.

Parenting Styles and Attachment Patterns

Parenting styles strongly influence attachment styles, which shape personality across the lifespan:

| Parenting Style | Common Attachment Pattern |

|---|---|

| Authoritative | Secure |

| Authoritarian | Anxious or Fearful |

| Permissive | Anxious |

| Neglectful | Avoidant or Disorganized |

Attachment patterns later affect:

-

Romantic relationships

-

Conflict resolution

-

Emotional intimacy

-

Self-regulation

Cultural Context: Parenting in Indian Families

In many Indian households:

-

Authoritarian parenting is normalized as “discipline”

-

Emotional expression is often discouraged

-

Obedience is prioritized over autonomy

While cultural values matter, psychological research shows that emotional responsiveness combined with structure leads to healthier personality development, regardless of culture.

Modern Indian parenting is slowly shifting toward authoritative approaches—balancing respect, boundaries, and emotional attunement.

Can Personality Be Changed in Adulthood?

Yes—personality can change in adulthood. While early parenting experiences leave deep psychological imprints, they do not permanently lock a person into one way of thinking, feeling, or relating. Personality is shaped by experience, and the brain retains the ability to reorganize itself throughout life. This capacity for change is what makes healing possible.

What often feels like a “fixed personality” is actually a set of learned emotional patterns—ways of coping, relating, and protecting oneself that once made sense in childhood.

Why Change Is Possible

Early experiences shape personality because they are repeated and emotionally powerful—not because they are unchangeable. In adulthood:

-

The brain still shows neuroplasticity (the ability to form new neural pathways)

-

Adults can reflect, choose, and practice new responses

-

Emotional experiences can be reprocessed and updated

With the right conditions, old patterns can be replaced with healthier ones.

1. Therapy: Rewriting Emotional Templates

Psychotherapy provides a safe, consistent relationship where old patterns can be understood and transformed.

-

Therapy helps identify unconscious beliefs such as “I am unsafe,” “I don’t matter,” or “Closeness leads to pain.”

-

Through emotional processing, reflection, and corrective experiences, these beliefs gradually soften.

-

Over time, new ways of regulating emotions, setting boundaries, and relating to others develop.

Therapy is not about changing who you are—it is about freeing who you were meant to be.

2. Secure Adult Relationships

Healing does not happen only in therapy. Safe, emotionally responsive adult relationships also reshape personality.

-

Being heard, respected, and emotionally supported challenges old attachment wounds

-

Consistent care helps the nervous system learn that connection is not dangerous

-

Healthy conflict and repair build emotional flexibility

Over time, relationships can become corrective emotional experiences, replacing fear-based patterns with trust.

3. Self-Awareness: Making the Unconscious Conscious

Change begins with awareness.

-

Recognizing emotional triggers

-

Understanding recurring relationship patterns

-

Noticing automatic reactions rooted in the past

When patterns are seen clearly, they lose some of their power. Self-awareness creates a pause between old conditioning and new choice.

This is the moment where growth begins.

4. Emotional Re-Parenting

Emotional re-parenting involves learning to give yourself what was missing earlier:

-

Validation instead of criticism

-

Comfort instead of dismissal

-

Structure instead of chaos

-

Compassion instead of shame

Through practices such as self-soothing, emotional labeling, boundary-setting, and inner child work, individuals slowly internalize a supportive inner voice.

This process does not erase the past—but it reduces its control over the present.

From Survival to Choice

Many adult personality traits—people-pleasing, emotional withdrawal, perfectionism, anger, or numbness—were once survival strategies. In adulthood, they may no longer be necessary.

With insight and support:

-

Reactive patterns become responsive choices

-

Fear-driven behaviors become values-driven actions

-

Identity shifts from “This is who I am” to “This is what I learned—and I can learn differently.”

Key Takeaways

-

Parenting styles profoundly shape emotional and personality development

-

Authoritative parenting supports the healthiest outcomes

-

Emotional neglect can be as harmful as overt abuse

-

Personality reflects learned emotional patterns—not personal failure

-

Healing is possible at any stage of life

Final Reflection

Children do not need perfect parents—they need emotionally present adults who offer safety, guidance, and understanding. Small mistakes do not harm a child’s development; emotional absence and inconsistency do. When caregivers are responsive and willing to repair after missteps, children feel secure and valued.

Emotional presence helps children feel seen and accepted. Safety—both emotional and physical—allows them to trust their feelings and regulate stress. Guidance through clear, consistent boundaries teaches responsibility without fear, while understanding nurtures healthy self-worth.

Personality grows where connection meets consistency.

Connection provides emotional security; consistency builds trust. Together, they create a foundation for resilience, confidence, and healthy relationships.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Do parents need to be perfect for healthy personality development?

No. Children do not need perfect parents. They need caregivers who are emotionally present, responsive, and consistent. Occasional mistakes are normal and do not harm development when followed by repair and reassurance.

2. What does “emotionally present parenting” mean?

Emotionally present parenting means being attentive to a child’s emotional needs—listening, validating feelings, and responding with empathy rather than dismissal, fear, or control.

3. How does consistency influence a child’s personality?

Consistency creates emotional safety. Predictable responses and boundaries help children develop trust, self-regulation, and confidence. Inconsistent caregiving can lead to anxiety, insecurity, or confusion.

4. Can emotional neglect affect personality even without abuse?

Yes. Emotional neglect—when a child’s feelings are repeatedly ignored—can strongly impact self-worth, attachment patterns, and emotional regulation, even if basic physical needs are met.

5. Is authoritative parenting really the healthiest style?

Research consistently shows that authoritative parenting—high warmth with clear boundaries—supports the most balanced outcomes in emotional regulation, self-esteem, and social competence.

6. If parenting was inconsistent or harmful, can personality still change later?

Yes. Through therapy, self-awareness, and secure adult relationships, individuals can unlearn maladaptive patterns and develop healthier personality traits over time.

Written by Baishakhi Das

Counselor | Mental Health Practitioner

B.Sc, M.Sc, PG Diploma in Counseling

Reference

-

American Psychological Association – Parenting styles and child development

https://www.apa.org/topics/parenting -

World Health Organization – Early child development

https://www.who.int/teams/maternal-newborn-child-adolescent-health-and-ageing/child-development -

National Institute of Mental Health – Child and adolescent mental health

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/child-and-adolescent-mental-health -

John Bowlby – Attachment and Loss

https://www.simplypsychology.org/bowlby.html -

Diana Baumrind – Parenting styles research

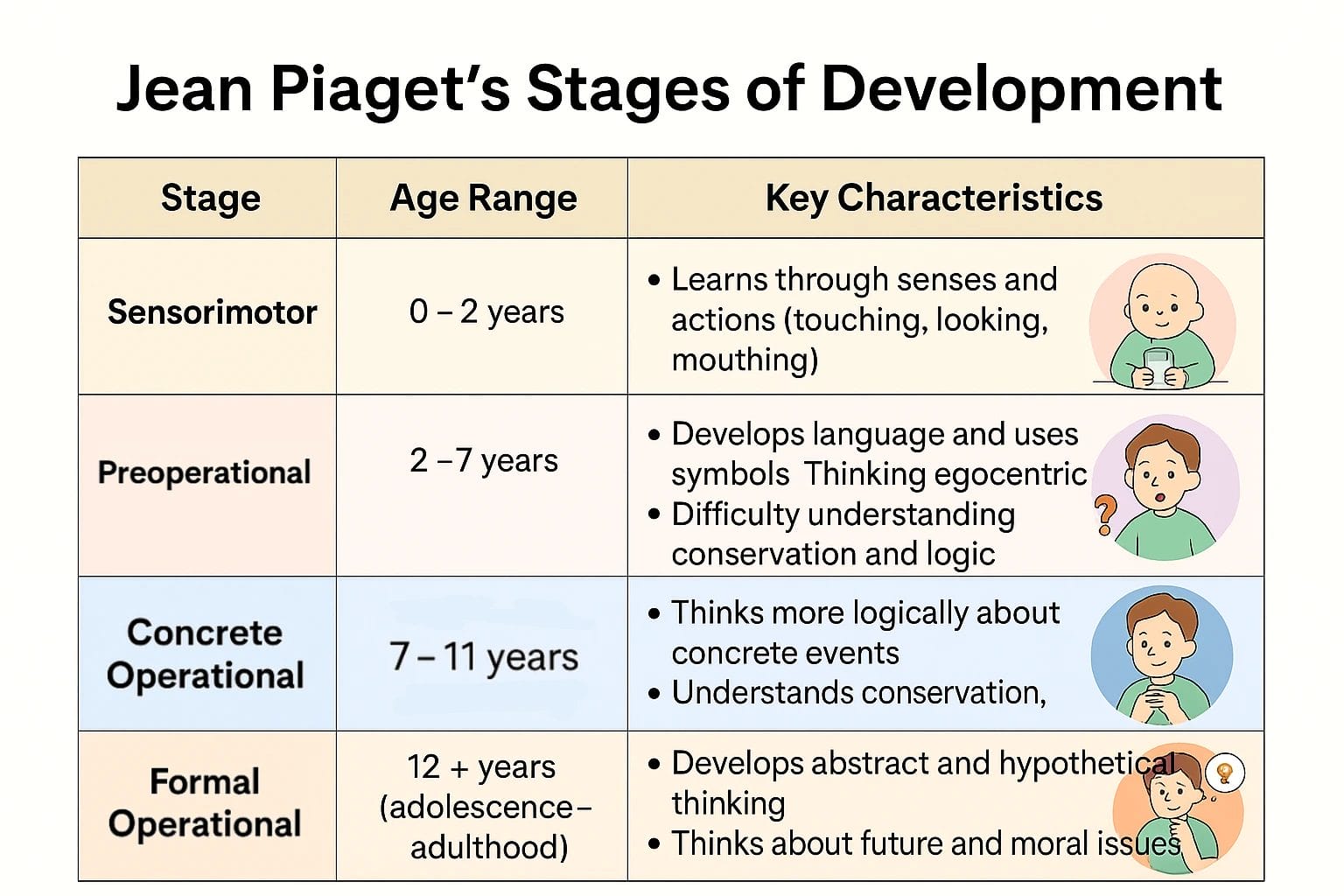

https://www.simplypsychology.org/baumrind.html - Moral Development Theory: Piaget vs Kohlberg

- Piaget’s Cognitive Development Theory