A Psychological Perspective with In-Depth Explanation

Birth order has long fascinated psychologists, parents, and researchers because siblings raised in the same family often develop strikingly different personalities, coping styles, and emotional patterns. Even when children share the same home, culture, and parenting values, their psychological experiences within the family are rarely the same. While genetics and environment play powerful roles in shaping personality, birth order adds another important psychological layer—influencing how children interpret attention, responsibility, competition, and belonging. Over time, these interpretations shape how individuals see themselves, relate to others, handle stress, and navigate the world.

The theory of birth order was first systematically explored by Alfred Adler, the founder of Individual Psychology. Adler believed that children are not shaped simply by objective family conditions, but by how they experience their position within the family. According to him, a child’s place among siblings creates unique emotional challenges and advantages, which influence motivation, self-concept, and interpersonal behavior. Birth order, in this view, affects the strategies children develop to gain significance, love, and a sense of belonging.

This article explains each birth order position in detail, exploring the typical strengths, challenges, and psychological patterns associated with first-borns, middle children, youngest children, and only children. At the same time, it is important to remember that birth order influences tendencies, not destiny. Personality remains flexible and is shaped continuously by life experiences, relationships, culture, and self-awareness. Understanding birth order is not about labeling people—but about gaining deeper insight into ourselves and others.

The Psychology Behind Birth Order

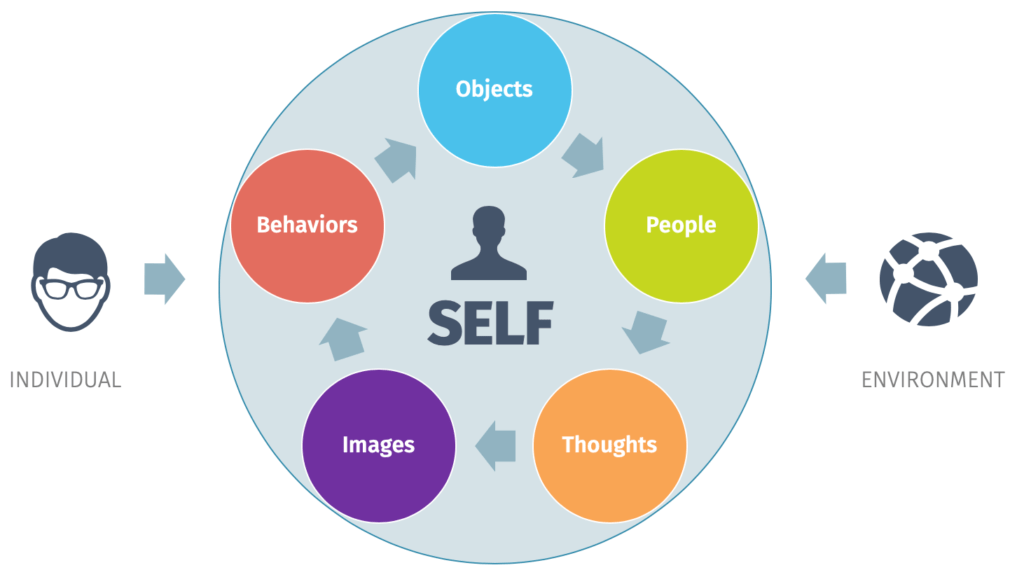

From a psychological standpoint, birth order influences how children interpret their place within the family system, and this interpretation affects several key developmental areas:

-

Parental attention – how much attention a child receives, when they receive it, and whether it feels secure or threatened

-

Expectations and responsibility – the level of pressure placed on a child to lead, comply, care for others, or achieve

-

Competition among siblings – how children compare themselves, seek uniqueness, or compete for recognition

-

Sense of belonging and significance – whether a child feels valued, noticed, and emotionally important within the family

Children are not passive recipients of these experiences. They adapt psychologically to their family role in order to secure love, attention, and emotional safety. Some learn to become responsible and dependable, others become agreeable peacemakers, while some rely on charm, independence, or achievement to feel valued. Over time, these early coping strategies become internalized patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving, often solidifying into stable personality traits that continue to influence relationships and self-identity well into adulthood.

First-Born Child: The Responsible Leader

Psychological Environment

The first-born child begins life as the sole recipient of parental attention, care, and expectations. During this early period, they often experience a strong sense of importance and security. However, when a younger sibling is born, the first-born commonly goes through what psychologists describe as “dethronement”—a sudden shift from being the center of the family to having to share attention and resources. This experience can feel like a loss of status or security, even if parents remain loving. As a result, many first-borns adapt by becoming more compliant, responsible, or achievement-oriented in an effort to regain approval and maintain their sense of significance. This early transition plays a powerful role in shaping their personality.

Common Personality Traits

First-born children often develop traits that reflect their early responsibilities and expectations, such as:

-

A strong sense of responsibility and duty

-

Organized, disciplined, and rule-oriented behavior

-

Natural leadership tendencies

-

High achievement motivation

-

Emotional maturity that appears advanced for their age

These traits often emerge because first-borns learn early that reliability and competence bring positive attention.

Emotional Patterns

Emotionally, first-borns may carry an internal pressure to “do things right.” They often experience:

-

Pressure to be a role model for younger siblings

-

Fear of making mistakes or failing

-

Anxiety related to losing control or disappointing others

Because praise and attention may feel linked to performance, some first-borns begin to equate love with achievement, which can contribute to perfectionism and self-criticism.

In Adulthood

As adults, first-born individuals often:

-

Perform well in leadership, management, or authority roles

-

Are reliable, loyal, and conscientious in relationships

-

Take responsibility seriously in family and work settings

However, they may also struggle with rigidity, overcontrol, or difficulty relaxing and delegating. Learning to separate self-worth from performance is often an important part of their emotional growth.

Middle Child: The Diplomat and Negotiator

Psychological Environment

Middle children often grow up feeling caught between siblings—no longer holding the privileges of the oldest, yet not receiving the special attention often given to the youngest. Because parental focus is frequently divided, middle children may perceive themselves as overlooked or less visible within the family. Psychologically, this experience encourages them to adapt by becoming highly aware of others’ needs and emotions. To maintain connection and belonging, they often learn to fit in, negotiate, and adjust—skills that foster strong social adaptability.

Common Personality Traits

As a result of this family position, middle children commonly develop traits such as:

-

Diplomatic and cooperative behavior

-

High emotional intelligence and social awareness

-

Flexibility and adaptability in changing situations

-

A strong sense of fairness and empathy

-

Independent thinking and problem-solving

They often carve out a unique identity by differentiating themselves from siblings rather than competing directly.

Emotional Patterns

Emotionally, middle children may develop:

-

Sensitivity to injustice or favoritism

-

A strong desire to be recognized for their individuality

-

Deep and meaningful peer relationships outside the family

They often learn early that connection is maintained through compromise, understanding others’ perspectives, and keeping harmony—sometimes at the cost of their own needs.

In Adulthood

In adult life, middle children often become:

-

Excellent mediators, negotiators, and team players

-

Loyal friends who value emotional balance and fairness

-

Socially skilled and adaptable in group settings

However, they may occasionally struggle with feeling unseen, undervalued, or unsure of their place, leading to periods of identity confusion. Learning to assert their own needs without fear of losing connection becomes an important part of their personal growth.

Youngest Child: The Charismatic Explorer

Psychological Environment

The youngest child typically grows up surrounded by older siblings and parents who are often more relaxed, experienced, and less rigid than they were with earlier children. Because much has already been “learned” by the family, the youngest may receive extra protection, indulgence, or leniency. Older siblings may also take on caregiving or directive roles. Psychologically, this environment encourages creativity, expressiveness, and social awareness, as the youngest learns to stand out and secure attention within an already established family system.

Common Personality Traits

Youngest children often develop traits that help them gain connection and recognition, such as:

-

Social and expressive communication style

-

Creativity and spontaneity

-

Willingness to take risks and explore new experiences

-

Strong sense of humor and playfulness

-

Attention-seeking behaviors

These traits often emerge as adaptive strategies to feel noticed and valued.

Emotional Patterns

Emotionally, youngest children may:

-

Use charm, humor, or charisma to gain approval

-

Avoid responsibility, especially if others tend to take charge

-

Fear not being taken seriously or being viewed as “the baby”

They often learn early that likability and emotional expressiveness are effective ways to build connection and maintain belonging.

In Adulthood

As adults, youngest children often grow into individuals who are:

-

Energetic, enthusiastic, and innovative

-

Comfortable in social settings with a strong interpersonal presence

-

Creative problem-solvers who bring fresh perspectives

However, they may struggle with discipline, consistency, or follow-through, especially in structured environments. They can also feel underestimated or dismissed, making it important for them to develop confidence in their competence alongside their natural charm.

Only Child: The Mature Individualist

Psychological Environment

Only children grow up in adult-centered environments without sibling rivalry or competition. They typically receive consistent, focused parental attention, which can foster security and emotional awareness. At the same time, the absence of siblings means fewer natural opportunities to practice sharing, negotiation, and conflict resolution in daily life. As a result, only children often become comfortable engaging with adults early on and may adopt more mature behaviors and communication styles than their peers.

Common Personality Traits

Only children frequently develop traits such as:

-

Emotional maturity and self-awareness

-

Strong self-reliance and independence

-

High achievement motivation

-

Comfort with solitude and self-directed activities

-

Well-developed verbal and communication skills

These traits often emerge from close interaction with adults and high parental involvement.

Emotional Patterns

Emotionally, only children may:

-

Develop perfectionistic tendencies

-

Feel intense pressure to succeed or meet expectations

-

Struggle with sharing control or delegating tasks

Because parental attention is often undivided, they may internalize high expectations, learning to equate success with approval.

In Adulthood

In adult life, only children are often:

-

Confident, self-directed, and internally motivated

-

Clear about their values and identity

-

Comfortable making independent decisions

However, they may sometimes struggle with collaboration, emotional vulnerability, or relying on others. Many only children are also deeply introspective, spending considerable time in self-reflection.

Important Moderating Factors

It is important to understand that birth order effects are not fixed or universal. Their influence depends heavily on context, including:

-

Age gaps between siblings

-

Gender roles and cultural expectations

-

Parenting style and emotional availability

-

Family stress, illness, or trauma

-

Blended, adoptive, or single-parent family structures

For example, a first-born with a large age gap may psychologically resemble an only child, while a middle child who assumes caregiving responsibilities may develop first-born–like traits. These moderating factors remind us that birth order shapes tendencies, but individual experience ultimately shapes personality.

What Birth Order Does Not Mean

It is important to approach birth order with balance and realism. Birth order influences tendencies, but it does not define a person’s full potential or future. Specifically, birth order:

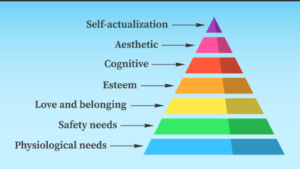

Intellectual capacity is not fixed by birth order – it develops through a blend of genetic potential, education, cognitive stimulation, and access to opportunities

Mental health outcomes cannot be predicted by sibling position – psychological conditions arise from complex interactions among biology, environment, relationships, and life experiences

Personality is not permanently set by family position – it remains flexible and capable of change across the lifespan through growth, insight, and experience

Human personality remains plastic and adaptable, shaped by new experiences, self-awareness, therapy, meaningful relationships, and personal growth. Early patterns can be understood, questioned, and reshaped.

Clinical and Counseling Perspective

In counseling psychology, birth order is used as a framework for understanding, not a diagnostic tool. Exploring birth order can help therapists and clients gain insight into:

-

Core beliefs about worth, significance, and belonging

-

Repeated relationship patterns

-

Typical conflict styles and coping strategies

-

Emotional roles learned within the family system

When used thoughtfully, birth order offers valuable context about how early family dynamics influence adult behavior, emotional responses, and interpersonal choices—without reducing individuals to labels.

Final Thoughts

Birth order shapes how we adapt, not who we must become.

Each birth order position carries its own strengths, challenges, and emotional lessons. With awareness, individuals can:

-

Appreciate their inherent strengths

-

Heal outdated or limiting patterns

-

Break unconscious family roles

-

Develop a more flexible, authentic sense of self

Understanding birth order is not about comparison or categorization—it is about self-understanding, compassion, and psychological growth.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is birth order in psychology?

Birth order refers to a child’s position in the family (first-born, middle, youngest, or only child) and how this position influences psychological development, personality traits, and behavior patterns.

2. Who introduced the birth order theory?

The birth order theory was introduced by Alfred Adler, who believed personality is shaped by social context and early family experiences.

3. Does birth order really affect personality?

Birth order does not determine personality, but it can influence tendencies, coping styles, and interpersonal behaviors, especially in early life.

4. Are first-born children more responsible?

Many first-borns develop responsibility and leadership traits due to early parental expectations, but this is not universal and depends on family dynamics.

5. Why are middle children considered adaptable?

Middle children often learn flexibility and diplomacy as they navigate between older and younger siblings, helping them develop strong social skills.

6. Are youngest children always attention-seeking?

Not always. Youngest children may use charm or humor to connect, but many also become creative, confident, and socially skilled adults.

7. Are only children lonely or selfish?

No. Research shows only children are often emotionally mature, independent, and capable of strong relationships, though they may prefer autonomy.

8. Can birth order predict success in life?

Birth order alone cannot predict success. Motivation, opportunities, education, and emotional support play much larger roles.

9. Does birth order affect relationships?

Yes, it can influence communication styles, conflict handling, and emotional expectations in friendships and romantic relationships.

10. Can birth order effects change over time?

Yes. Personality is plastic and evolves with life experiences, therapy, self-awareness, and personal growth.

11. How do age gaps affect birth order influence?

Large age gaps can alter birth order effects. For example, a first-born with a large gap may function psychologically like an only child.

12. Does culture influence birth order traits?

Absolutely. Cultural expectations, gender roles, and parenting styles significantly shape how birth order traits develop.

13. Is birth order used in counseling or therapy?

Yes. Therapists use birth order as an exploratory tool to understand family roles, emotional patterns, and core beliefs—not as a label.

14. Can understanding birth order help with self-growth?

Yes. Awareness helps individuals recognize strengths, heal old patterns, and break unconscious family roles.

15. Is birth order more important than genetics?

No. Personality develops through an interaction of genetics, environment, relationships, and personal experiences—birth order is just one factor.

Written by Baishakhi Das

Counselor | Mental Health Practitioner

B.Sc, M.Sc, PG Diploma in Counseling

Reference Links

-

American Psychological Association (APA) – Personality Development

https://www.apa.org/topics/personality -

Simply Psychology – Birth Order Theory

https://www.simplypsychology.org/birth-order.html -

Adlerian Psychology Overview

https://www.verywellmind.com/alfred-adler-biography-2795502 - Type A & Type B Personality Theory