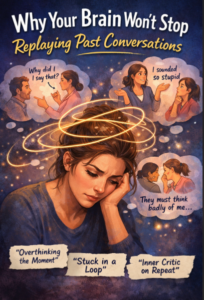

Have you ever lay in bed or sitting there when suddenly you hear yourself conversing with someone in the past like your previous conversation? Something you said. Something that you wish you could have said. A tone you’re now questioning. The act recurs over and over, but it is not always comfortable, regrettable, or nervous. This is aggravated by the fact that these thoughts normally come when all the other things are silent at night, when you are taking a rest, or when you are supposed to be having a peaceful moment and you find yourself alone with your inner talk.

Such an experience is so widespread–and it does not mean that something is wrong with you. It is an indication that the brain attempts to defend, process and meaning making around social experiences. These moments come back into your mind to find meaning, closure, or reassurance, particularly when a conversation had been emotionally charged or unresolved. Instead of it being a weakness, this replay shows a very human desire to fit in, to be heard, and to feel emotionally secure in all our relationships with other people.

1. The Brain Is Wired for Social Survival

1. The Brain Is Wired for Social Survival

Humans are social beings. Thousands of years ago, being part of a group was the guarantee of protection, safety and existence. Due to this evolutionary output, the brain allocates additional significance to the social engagement, particularly to the ones, which are awkward, emotionally significant, or unbroken. We are in a state of constant scanning of signals to do with approval, denial, and relationship.

The brain is stressed when a conversation is confusing or uncomfortable, which is why it is important. The replaying of it is the manner in which the brain engages in an effort to comprehend and avoid pain in the future in a social context. The questions under the loop are silent, such as:

“Did I say something wrong?”

“Was I misunderstood?”

Will this alter the perception they have of me or change our relationship?

2. Unfinished Emotional Processing

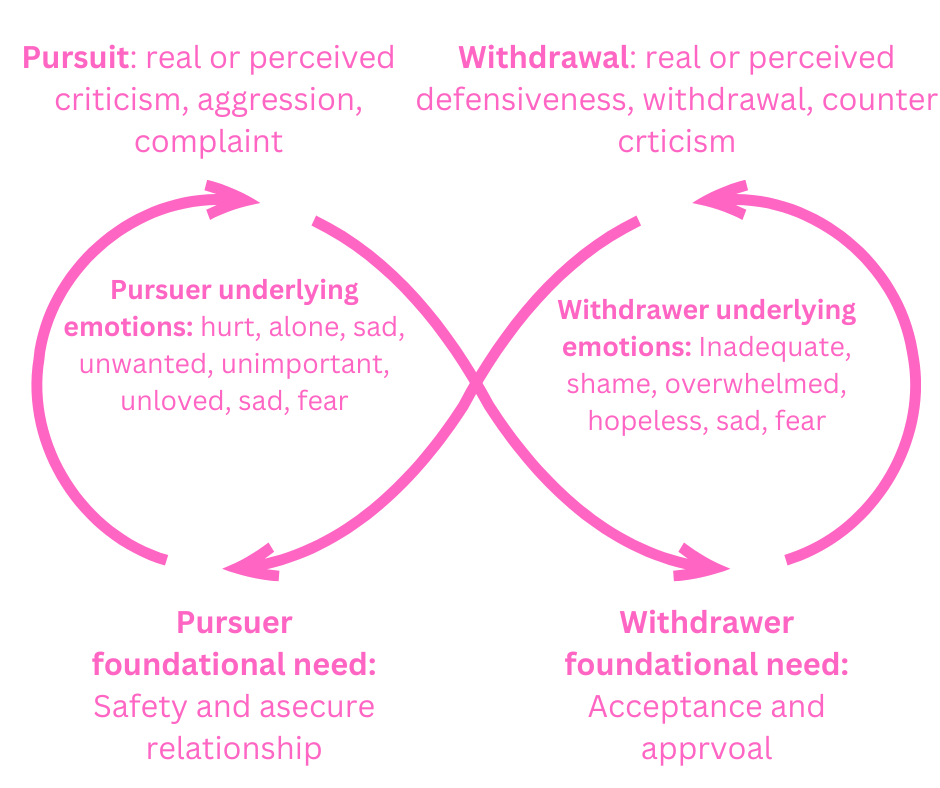

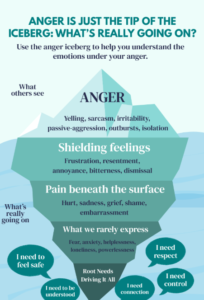

Most of the discussions are cut short before feelings are well worked out. At the moment, you can suppress your emotions to be polite, calm, or emotionally restrained, particularly when you feel you are not safe, inconvenienced or inappropriate to express them. Those emotions are repressed by your body so that you can get through the interaction.

With time when the nervous system ultimately lets go, the emotions that have been repressed start to appear. That is the reason why the mind re-plays the dialogue in the silent times. The replay is not of the words spoken but of the unspoken emotions which were there, linked to the words, ready to be recognized, comprehended, and discharged.

3. Rumination: When Thinking Turns into a Loop

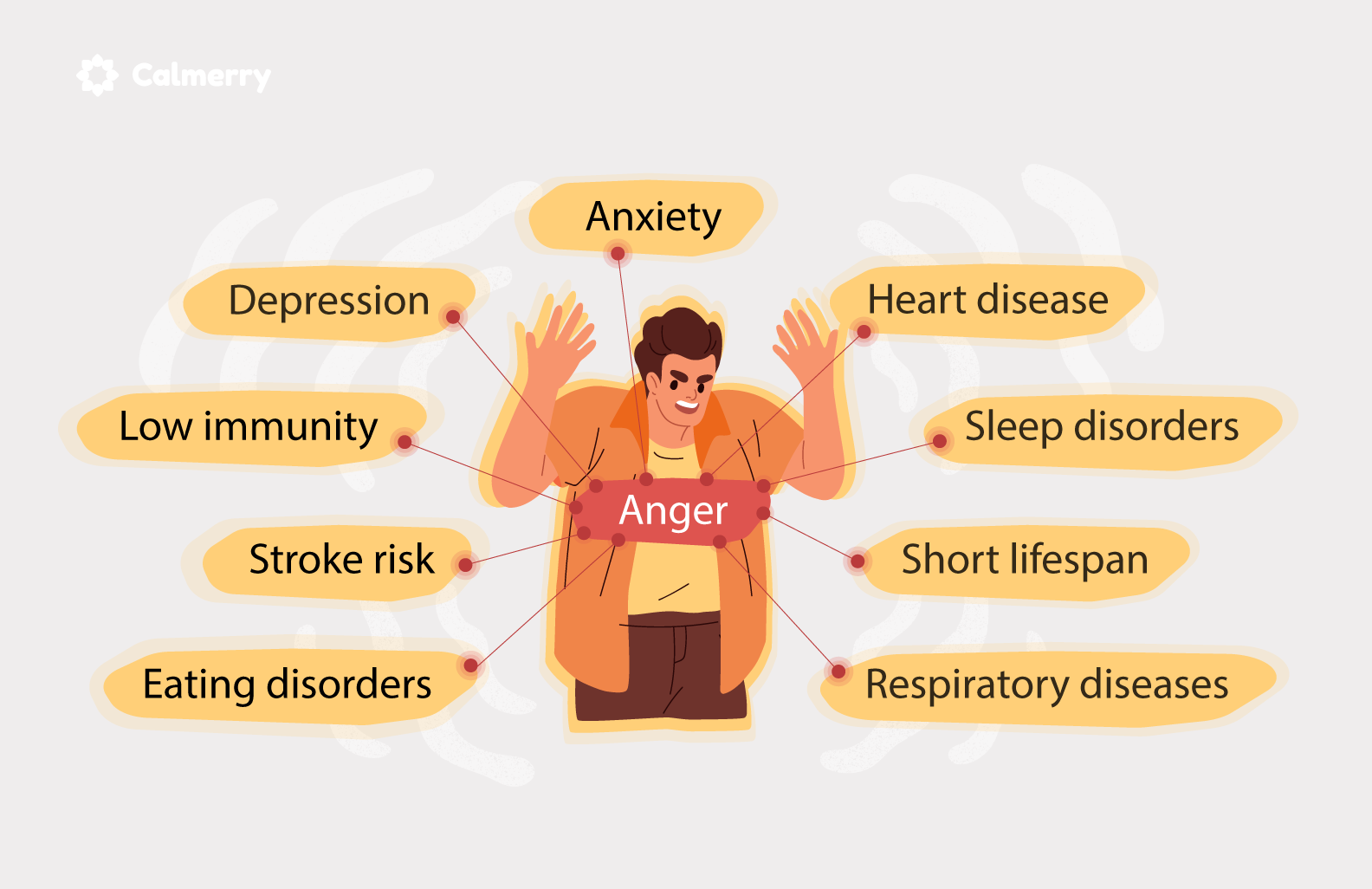

Rereading conversations could slowly degenerate into rumination a mental cycle in which the brain is continually processing the same incident without having a conclusion or a relief. This repetitive thinking can be a cause of more emotional distress instead of relief. Rumination usually presents itself in association with:

Anxiety

Low self-esteem

A history of trauma

Perfectionism

The mind continues to spin around the same thoughts appearing to replay details and imagine different solutions and events, hoping that at some point the explanation or relief will suddenly come. Sadly enough, this loop is not always answered, the loop only extends the emotional distress.

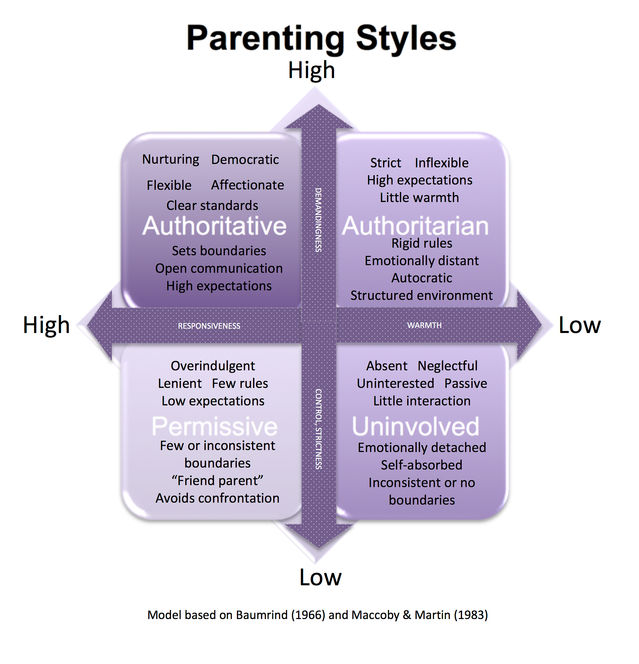

4. The Inner Critic Takes Over

In these mental acting games, most individuals become cruel and critical to themselves:

“Why did I say that?”

“I sounded stupid.”

“They must think badly of me.”

There is nothing true about this inner critic the criticism is based on the fear. It is attempting to shield you against rejection or embarrassment that might come later, although it is a painful way. This voice frequently expresses historical experiences in which a person was probably criticized, shamed, or punished instead of being patient and understanding. In the course of time, the mind gets to condition itself to pre-erect self, with the hope that the self-criticism will help to stop the external criticism, although it does not necessarily do good.

5. The Nervous System and the “Threat Response”

Psychologically, it is common to relate the re-enactment of conversations to the nervous system being in a high level of alertness. Your system, when subjected to any kind of emotional threat (rejection, conflict, embarrassment, or disapproval), finds it hard to settle down and achieve a relaxed, controlled state. The body and mind remains alert even after the scenario has been experienced.

In reaction the brain re-plays the situation, trying to theorize it and avoid such an emotional injury in future. This circularity is not meant to happen–this is survival by default because the human mind needs to feel safe and secure.

6. Trauma and Emotional Memory

In the case of persons who suffered emotional or relationship trauma, the replays may run deeper. The previous experiences of misunderstanding, being criticized, dismissed, or feeling unsafe may be triggered by old conversations. When this happens it does not mean the mind is reacting to the current interaction alone it is reacting to past emotional records.

It is not really a replay of this conversation. It is a question of what the moment will be embodying in its emotional aspect echoing old wounds that are not yet completely healed or recognized.

What Actually Helps

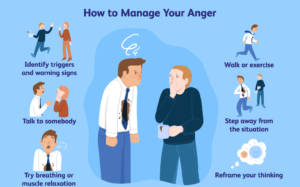

- Name what you’re feeling, not just what you said

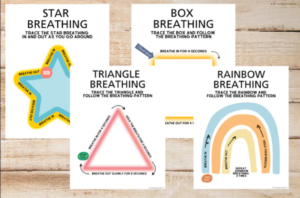

(e.g., embarrassment, hurt, fear of rejection) - Gently interrupt the loop

Try grounding techniques like slow breathing or noticing physical sensations. - Practice self-compassion

Ask yourself: “What would I say to a friend in this situation?” - Accept imperfection

No conversation is ever flawless. Human connection doesn’t require perfection—only presence. - If it’s persistent, therapeutic support can help uncover deeper patterns behind rumination and emotional looping.

A Reframe Worth Remembering

Your mind is not repeating some old discussions to torment or torment you. It is attempting – in many cases clumsy and unsuccessful – to keep you safe, to make sense out of what has occurred, to get you to feel secure and to belong. These emotional circles are the result of a profound human desire to fit in, to be comprehended and not to be hurt emotionally.

When you receive these thoughts with curiosity, not criticism, that is, by asking yourself questions like “What was I feeling?” and not What is wrong with me? the loop starts getting unstuck. Not instantly. Not completely. But gradually, gradually enough to make breathing room in your head.

And in some cases, that pity suffices to allow that dialogue to finally subside and does not have to be repeated to be listened to.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Why do old conversations replay in my mind?

Because the brain tries to process unresolved emotions, social uncertainty, or perceived threats related to connection and belonging.

2. Is replaying conversations a sign of anxiety?

It can be associated with anxiety, but not everyone who replays conversations has an anxiety disorder.

3. Why does this happen more at night?

At night, distractions reduce and the nervous system slows down, allowing suppressed thoughts and emotions to surface.

4. Is this the same as overthinking?

Yes, it’s a form of overthinking, often linked specifically to social interactions and emotional safety.

5. What is rumination?

Rumination is repetitive thinking about past events without reaching resolution or relief.

6. Can trauma cause conversation replaying?

Yes. Emotional or relational trauma can make the brain more sensitive to social cues and perceived rejection.

7. Why am I so self-critical during these replays?

The inner critic often develops from past experiences where mistakes were judged harshly rather than met with understanding.

8. Do perfectionists replay conversations more?

Yes. Perfectionism increases fear of mistakes and social evaluation, fueling mental loops.

9. Is my brain trying to fix something?

Yes. The brain is attempting to prevent future emotional harm by analyzing past interactions.

10. Does replaying conversations mean I did something wrong?

Not necessarily. Often, it reflects emotional sensitivity rather than actual mistakes.

11. How can I stop replaying conversations?

Gentle grounding, naming emotions, self-compassion, and nervous system regulation help reduce the loop.

12. Should I distract myself when this happens?

Temporary distraction can help, but emotional acknowledgment leads to longer-term relief.

13. Can mindfulness help?

Yes. Mindfulness helps you observe thoughts without getting pulled into them.

14. When should I seek therapy?

If replaying conversations interferes with sleep, work, or emotional well-being, therapy can be helpful.

15. Will this ever stop completely?

The goal isn’t complete elimination but reducing intensity and responding with compassion instead of fear.

Written by Baishakhi Das

Counselor | Mental Health Practitioner

B.Sc, M.Sc, PG Diploma in Counseling

Reference

-

American Psychological Association – Rumination & Anxiety

https://www.apa.org -

National Institute of Mental Health – Anxiety Disorders

https://www.nimh.nih.gov -

Harvard Health Publishing – Overthinking and Mental Health

https://www.health.harvard.edu -

Polyvagal Theory (Stephen Porges) – Nervous System & Safety

https://www.polyvagalinstitute.org - Reasons You Overthink at Night

This topic performs well due to rising searches around men’s mental health, workplace stress, and burnout recovery. Combining emotional insight with practical steps increases engagement and trust.