The idea of a fully functioning person comes from humanistic psychology and offers one of the most optimistic views of human potential. Instead of concentrating on pathology, dysfunction, or diagnosis, this perspective shifts the focus toward growth, authenticity, and psychological health. It asks a fundamentally different question:

What does psychological health look like when a person is allowed to grow freely and live in alignment with their true self?

This approach moves away from fixing what is “wrong” and toward understanding what helps a person thrive. The answer does not lie in perfection, constant happiness, or rigid emotional control. A fully functioning person still experiences pain, fear, doubt, and uncertainty. What distinguishes psychological health is not the absence of struggle, but the ability to remain open and responsive to experience.

Psychological well-being, from this view, involves openness to emotions, flexibility in thinking, trust in one’s inner signals, and the capacity to live authentically rather than defensively. Instead of suppressing feelings or shaping the self to meet external expectations, a fully functioning person engages with life honestly, adapts to change, and continues to grow through experience.

This concept reframes mental health as a dynamic process of becoming, not a fixed state to be achieved.

Origin of the Concept

The concept of the fully functioning person emerged from the work of Carl Rogers, one of the founders of humanistic psychology. Rogers rejected the idea that human beings are inherently broken or flawed. Instead, he viewed people as naturally oriented toward growth, fulfillment, and psychological health. He called this innate drive the actualizing tendency.

Rogers argued that psychological distress does not arise because people lack potential. It emerges when environments interfere with natural growth. Conditions such as conditional acceptance, emotional invalidation, chronic criticism, or pressure to conform can block this process. When individuals feel they must deny parts of themselves to gain love or approval, they disconnect from their authentic experience.

A fully functioning person, in Rogers’ view, is someone whose growth has not been excessively restricted. Such a person remains free to experience emotions openly, trust their inner guidance, and continue developing in ways that feel genuine and self-directed. Psychological health, therefore, reflects not perfection, but the freedom to grow without fear of losing acceptance.

The Actualizing Tendency

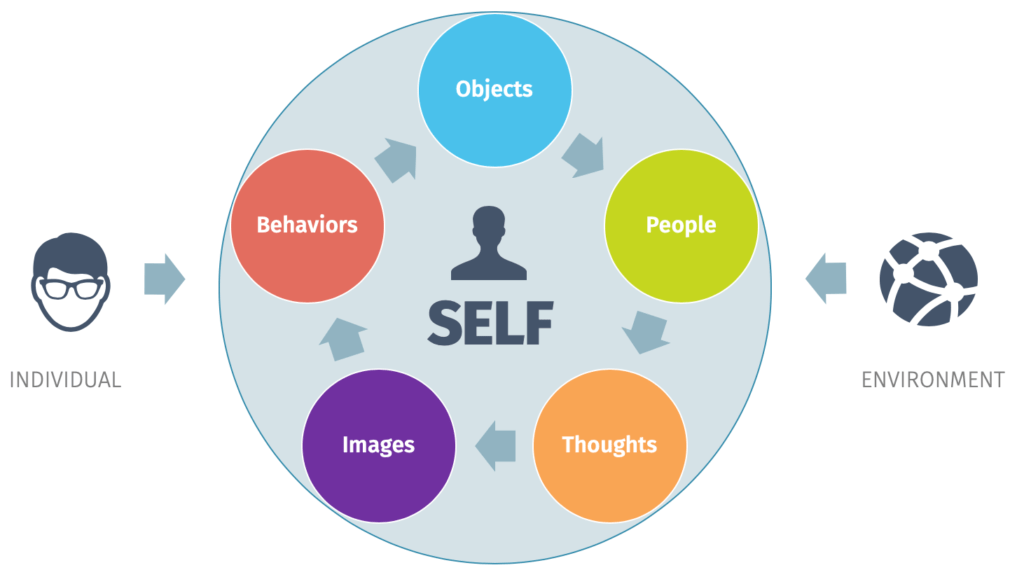

At the heart of Rogers’ theory is the actualizing tendency—the natural drive within every individual to develop their abilities, express their true self, and move toward psychological wholeness.

This tendency:

-

Exists in all people

-

Operates naturally when conditions are supportive

-

Pushes toward growth, not destruction

When the environment allows emotional safety, empathy, and acceptance, this tendency guides a person toward healthy functioning.

Fully Functioning Person: Core Definition

A fully functioning person is not someone who has no problems or negative emotions. Instead, they are someone who:

-

Is open to inner experience

-

Trusts their feelings and perceptions

-

Lives authentically rather than defensively

-

Adapts flexibly to life’s challenges

-

Continues to grow psychologically

Rogers described this state as a process, not a fixed endpoint. A fully functioning person is always becoming.

Key Characteristics of a Fully Functioning Person

1. Openness to Experience

Fully functioning individuals remain open to both pleasant and unpleasant emotions. They do not deny, distort, or suppress their inner experiences to protect their self-image.

This includes:

-

Accepting sadness without shame

-

Acknowledging anger without guilt

-

Experiencing joy without fear

Emotions act as information, not threats.

2. Existential Living (Living in the Present)

Rather than rigidly following rules from the past or fears about the future, fully functioning people engage with life moment by moment.

They respond to situations as they are, not as they “should” be. This allows flexibility, creativity, and genuine engagement with reality.

3. Trust in the Organism

Rogers believed that psychologically healthy individuals trust their internal signals—emotions, intuition, bodily responses—when making decisions.

This does not mean impulsivity. It means:

-

Listening inward before seeking external validation

-

Using feelings as guides rather than enemies

-

Making choices aligned with inner values

This internal trust replaces dependence on approval.

4. Experiential Freedom

Fully functioning people experience a sense of choice in their lives. Recognize constraints but do not feel psychologically trapped by them.

-

They can choose responses even when situations are difficult

-

They are not controlled entirely by the past

-

Growth remains possible

This sense of agency supports resilience.

5. Creativity and Adaptability

Psychological openness fosters creativity—not only in art, but in problem-solving, relationships, and coping.

Fully functioning individuals:

-

Adapt rather than rigidly control

-

Learn from experience

-

Revise beliefs when new information appears

They remain flexible rather than defensive.

Fully Functioning Person vs Perfectionism

A common and critical misunderstanding is equating full functioning with perfection. In reality, these two reflect very different psychological processes.

A fully functioning person does not aim to eliminate fear, mistakes, or conflict. Instead, they relate to these experiences without allowing them to define their worth or identity. Such a person:

-

Feels fear but does not live in fear, allowing caution without paralysis

-

Makes mistakes without collapsing into shame, using errors as information rather than self-condemnation

-

Experiences conflict without losing identity, staying connected to self even during disagreement

-

Accepts limitations without self-rejection, recognizing limits as part of being human

Perfectionism, by contrast, grows out of conditions of worth. It ties value to performance, correctness, or approval and fuels constant self-monitoring and anxiety. Full functioning reflects unconditional self-regard—the ability to value oneself regardless of success, failure, or emotional state.

In short, perfectionism demands flawlessness to feel safe, while full functioning allows authenticity to guide growth.

Role of Unconditional Positive Regard

Carl Rogers emphasized that psychological growth flourishes in the presence of unconditional positive regard—the experience of being valued as a person regardless of behavior, success, or failure. This form of acceptance communicates a powerful message: your worth does not depend on performance or approval.

When children receive conditional acceptance—messages such as “You are good only if…”—they begin to organize their self-concept around external expectations. Over time, they may develop:

-

Conditions of worth, tying value to behavior or achievement

-

Defensive self-concepts, hiding parts of themselves to avoid rejection

-

Fear of authenticity, believing their true self is unacceptable

In contrast, when children experience unconditional acceptance, they internalize a stable sense of worth. This environment supports the development of:

-

Self-trust, allowing them to rely on their inner experience

-

Emotional openness, enabling healthy expression of feelings

-

Psychological flexibility, adapting to life without excessive defense

Therapy often aims to recreate these conditions by offering empathy, consistency, and nonjudgmental presence. Within such an environment, individuals naturally move toward greater authenticity, integration, and full psychological functioning.

Fully Functioning Person and Mental Health

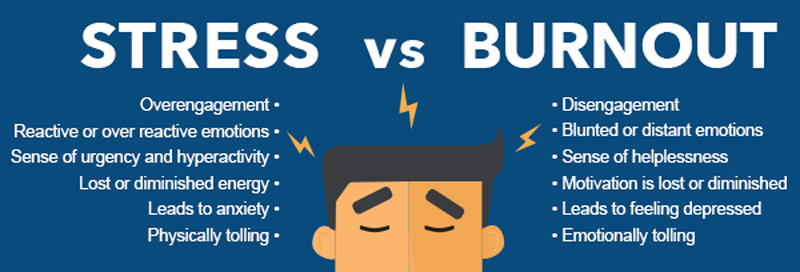

Being a fully functioning person does not mean living without anxiety, sadness, stress, or emotional pain. Human experience naturally includes discomfort and uncertainty. Psychological health, from this perspective, lies not in eliminating these experiences but in the ability to relate to them without excessive defense, denial, or self-judgment.

In this view, mental health involves:

-

Emotional awareness — recognizing and understanding feelings as they arise

-

Acceptance rather than avoidance — allowing emotions to be experienced instead of suppressed or feared

-

Integration of experience — bringing thoughts, emotions, and actions into alignment

-

Ongoing growth — remaining open to change, learning, and self-development

Rather than aiming solely for symptom reduction, this perspective reframes mental health as self-congruence—living in harmony with one’s inner experience. When people feel free to acknowledge what they truly feel and need, distress loses its power to fragment the self, and growth becomes possible even in the presence of difficulty.

Fully Functioning Person in Relationships

In relationships, fully functioning individuals tend to:

-

Communicate honestly

-

Tolerate emotional intimacy

-

Respect boundaries

-

Repair conflicts rather than avoid them

-

Allow others to be different

They do not need to lose themselves to maintain connection.

Barriers to Becoming Fully Functioning

Common obstacles include:

-

Childhood emotional neglect

-

Conditional parenting

-

Trauma and chronic invalidation

-

Cultural pressure to conform

-

Fear-based self-esteem

These barriers do not eliminate the actualizing tendency—they restrict its expression.

Therapy and the Fully Functioning Person

Client-centered therapy aims to remove these barriers rather than “fix” the person.

Therapy provides:

-

Empathy

-

Congruence

-

Unconditional positive regard

Over time, clients naturally move toward greater openness, self-trust, and psychological integration.

A Process, Not a Destination

Rogers emphasized that full functioning is not a final state. It is a continuous process of becoming more open, more authentic, and more responsive to life.

There is no final version of the self—only deeper alignment.

A Gentle Closing Reflection

A fully functioning person is not fearless, flawless, or endlessly confident.

They are real.

Feel deeply without fear.

Respond honestly without defense.

Trust their inner experience without doubt.

Allow themselves to change without shame.

Psychological health is not about becoming someone else.

It is about becoming more fully yourself.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is a fully functioning person in psychology?

A fully functioning person is someone who lives with openness to experience, self-trust, emotional awareness, and psychological flexibility. The concept emphasizes growth and authenticity rather than perfection.

2. Who introduced the concept of the fully functioning person?

The concept was introduced by Carl Rogers, a founder of humanistic psychology, as part of his person-centered theory of psychological health.

3. Is a fully functioning person always happy?

No. Fully functioning individuals experience anxiety, sadness, and stress like anyone else. Psychological health lies in how they relate to these emotions—not in avoiding them.

4. How is full functioning different from perfectionism?

Perfectionism is driven by conditions of worth and fear of failure. Full functioning reflects unconditional self-regard, where mistakes and limitations do not threaten self-worth.

5. What role does unconditional positive regard play?

Unconditional positive regard allows individuals to feel valued regardless of behavior or success. This acceptance supports emotional openness, self-trust, and healthy psychological development.

6. Can therapy help someone become more fully functioning?

Yes. Person-centered and trauma-informed therapies aim to reduce defenses, increase self-congruence, and create conditions that support natural psychological growth.

7. Is being fully functioning a fixed state?

No. Rogers described full functioning as an ongoing process of becoming, not a final destination. Growth continues throughout life.

Written by Baishakhi Das

Counselor | Mental Health Practitioner

B.Sc, M.Sc, PG Diploma in Counseling

Reference

-

Rogers, C. R. (1959). A Theory of Therapy, Personality, and Interpersonal Relationships

https://www.simplypsychology.org/carl-rogers.html -

American Psychological Association – Humanistic Psychology

https://www.apa.org/education-career/guide/subfields/humanistic -

Rogers, C. R. (1961). On Becoming a Person

https://www.hmhbooks.com/shop/books/On-Becoming-a-Person/9780395755318 -

Siegel, D. J. (2012). The Developing Mind

https://www.guilford.com/books/The-Developing-Mind/Daniel-Siegel/9781462542758 -

van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/220644/