A Deep Psychological Explanation of the Cycle Behind Ongoing Conflicts

Many couples share a frustrating experience: the same argument keeps coming back, even after apologies, discussions, or temporary resolutions. Although the topic may change—money, time, family, communication—the emotional fight feels identical. This repetition is not a sign that partners are immature or incompatible. Instead, it reflects unresolved psychological patterns operating beneath the surface of the relationship.

To understand why arguments repeat, we must look beyond words and focus on emotions, attachment needs, learned coping styles, and unmet expectations.

1. Repeated Arguments Are About Needs, Not Topics

At a surface level, couples argue about:

-

Time

-

Attention

-

Responsibilities

-

Trust

-

Boundaries

However, beneath these topics lie unmet emotional needs, such as:

When these needs r

- Emotional validation

- Psychological safety

- Attentive understanding

- Mutual respect

emain unmet, the mind keeps reusing the same conflict as a way to signal distress.

👉 Key insight:

Arguments repeat because the need behind them has not been addressed.

2. The Role of Attachment Styles

Attachment theory plays a central role in recurring conflicts.

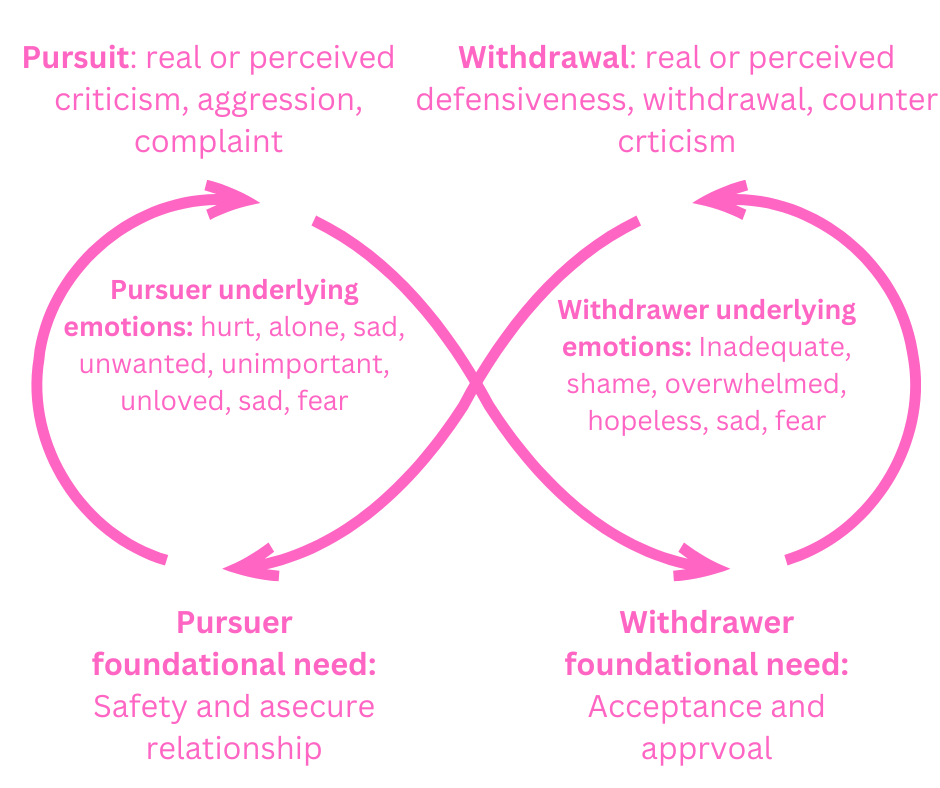

Common Pattern: The Pursue–Withdraw Cycle

-

One partner seeks closeness, reassurance, or discussion (anxious response)

-

The other retreats, shuts down, or avoids conflict (avoidant response)

This creates a loop:

-

The more one pursues → the more the other withdraws

-

The more one withdraws → the more the other escalates

Neither partner feels safe, heard, or understood.

👉 Over time, this pattern becomes automatic, not intentional.

3. Emotional Triggers from Past Experiences

Many arguments are not about the present moment, but about old emotional wounds being activated.

Common triggers include:

-

Childhood emotional neglect

-

Past relationship betrayal

-

Criticism or rejection experiences

-

Feeling controlled or abandoned earlier in life

When triggered:

-

The nervous system reacts as if the past is happening again

-

Logic shuts down

-

Emotional intensity increases rapidly

This is why couples often say:

“We keep fighting, but I don’t even know why anymore.”

4. Poor Repair, Not Poor Communication

Many couples communicate frequently—but repair poorly.

Repair refers to:

-

Taking responsibility

-

Acknowledging hurt

-

Offering emotional reassurance

-

Rebuilding safety after conflict

When repair is missing:

-

The argument ends, but the emotional injury remains

-

Resentment quietly accumulates

-

The same issue resurfaces later with greater intensity

👉 Unrepaired conflict always returns.

5. Cognitive Distortions That Fuel Repetition

Certain thinking patterns make arguments cyclical:

-

Mind reading: “You don’t care about me.”

-

All-or-nothing thinking: “You never listen.”

-

Personalization: “You’re doing this to hurt me.”

-

Catastrophizing: “This relationship is doomed.”

These distortions turn disagreements into threats to the relationship, making calm resolution nearly impossible.

6. Emotional Regulation Difficulties

When one or both partners struggle to regulate emotions:

-

Anger escalates quickly

-

Shutdown or stonewalling occurs

-

Defensive reactions replace listening

As a result:

-

The nervous system remains in fight-or-flight mode

-

Conversations become reactive rather than reflective

-

The same arguments repeat because regulation never occurs

7. Power, Control, and Unspoken Roles

Repeated arguments often hide struggles around:

-

Decision-making power

-

Emotional labor

-

Gender or cultural role expectations

-

Feeling dominated or invisible

When these dynamics are not openly discussed, they surface indirectly through repeated conflict.

8. Why “Solving the Problem” Doesn’t Work

Couples often try to:

-

Find logical solutions

-

Prove who is right

-

End the argument quickly

However, emotional problems cannot be solved logically.

What partners usually need instead:

-

Validation before solutions

-

Emotional safety before compromise

-

Understanding before agreement

Without this, solutions fail—and the argument returns.

9. How Repeating Arguments Affect Relationships

Over time, unresolved cycles lead to:

-

Emotional distance

-

Loss of intimacy

-

Chronic resentment

-

Feeling lonely within the relationship

-

Questioning the relationship’s future

Importantly, many couples who separate say:

“It wasn’t one big fight—it was the same fight over and over.”

10. Breaking the Cycle: What Actually Helps

1. Identify the Pattern, Not the Person

Shift from:

“You are the problem”

to

“This pattern is the problem.”

2. Name the Underlying Need

Ask:

-

“What am I really needing right now?”

-

“What fear is driving this reaction?”

3. Slow Down the Nervous System

-

Pause heated conversations

-

Return when emotions settle

-

Focus on regulation before resolution

4. Practice Repair Conversations

-

Acknowledge hurt

-

Validate emotions

-

Reassure commitment and care

5. Seek Professional Support

Couples therapy helps:

-

Identify unconscious patterns

-

Improve emotional safety

-

Teach regulation and repair skills

Conclusion

Arguments repeat in relationships not because partners are incapable, but because unmet emotional needs, unresolved wounds, and automatic patterns keep replaying. Until these deeper layers are addressed, the mind uses conflict as a signal for connection and safety.

Healing begins when couples stop asking:

“How do we stop fighting?”

and start asking:

“What is this fight trying to tell us?”

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Why do the same arguments keep repeating in relationships?

Arguments repeat because the underlying emotional need or unresolved issue is not addressed. Even if the topic changes, the same emotional trigger—such as feeling unheard, unsafe, or unvalued—keeps resurfacing.

2. Are repeating arguments a sign of incompatibility?

Not necessarily. Repeating arguments usually reflect unresolved emotional patterns, attachment styles, or communication cycles, rather than lack of compatibility.

3. What role do attachment styles play in repeated conflicts?

Attachment styles strongly influence conflict patterns. For example, an anxious partner may seek reassurance, while an avoidant partner may withdraw, creating a pursue–withdraw cycle that repeats over time.

4. Why do arguments feel emotionally intense even over small issues?

Small disagreements often activate old emotional wounds or past experiences, causing the nervous system to react as if there is a serious threat. This makes conflicts feel bigger than the situation itself.

5. Why doesn’t logical problem-solving stop repeated arguments?

Because most recurring conflicts are emotion-based, not logic-based. Without emotional validation and repair, solutions fail and the same argument returns.

6. How does emotional regulation affect relationship conflicts?

When emotional regulation is poor, partners react impulsively, shut down, or become defensive. Without regulation, healthy communication and repair are impossible, leading to repeated arguments.

7. Can repeated arguments damage a relationship long term?

Yes. Over time, unresolved conflict cycles can lead to emotional distance, resentment, reduced intimacy, and relationship burnout, even if love is still present.

8. How can couples break the cycle of repeating arguments?

Breaking the cycle involves:

Identifying the pattern, not blaming the person

Understanding the emotional need behind the conflict

Practicing emotional regulation and repair

Seeking professional help when needed

9. When should couples seek therapy for recurring conflicts?

Couples should seek therapy when:

The same arguments repeat without resolution

Conflicts escalate quickly

Emotional shutdown or withdrawal becomes common

Both partners feel unheard or hopeless

10. Can repeating arguments be a sign of trauma or past experiences?

Yes. Trauma, childhood neglect, or previous relationship wounds often contribute to automatic emotional reactions, making conflicts repeat even in otherwise healthy relationships.

Written by Baishakhi Das

Counselor | Mental Health Practitioner

B.Sc, M.Sc, PG Diploma in Counseling

Reference

American Psychological Association – Relationships & Conflict

https://www.apa.org/topics/relationshipsGottman Institute – Why Couples Fight Repeatedly

https://www.gottman.com/blogSimply Psychology – Attachment Theory in Relationships

https://www.simplypsychology.org/attachment.htmlNational Institute of Mental Health – Emotional Regulation

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topicsWorld Health Organization – Mental Health and Relationships

https://www.who.int/teams/mental-health-and-substance-use- Cognitive Behavioral Theory: How Thoughts Control Emotions

- Attachment Theory: How Childhood Bonds Shape Adult Relationships