Introduction

Learned Helplessness Theory explains how repeated exposure to uncontrollable and unavoidable negative experiences can gradually lead individuals to believe that their actions no longer make a meaningful difference.

Consequently, individuals start anticipating failure no matter how hard they struggle. This belief system continuously and steadily leads to passivity, lack of motivation, emotional distress, and distorted ways of thinking, even in cases when the actual change opportunities are presented. As a result, people end up not even trying, in most instances, not due to lack of ability but because they have been taught that it is pointless that they make efforts. Through this, helplessness becomes a vicious cycle, which eventually inhibits action, growth and adaptive coping.

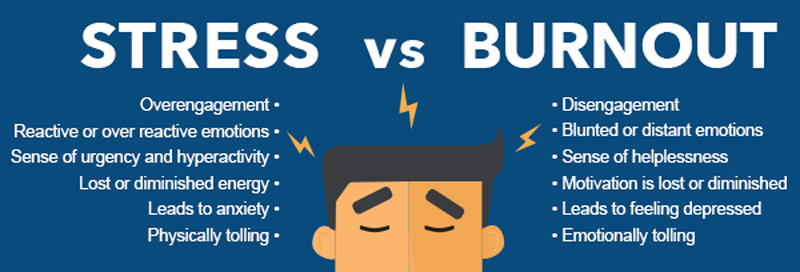

In addition to that, the theory has significantly impacted psychology because it provides a simple and organized system through which individuals can explain why they cannot come out of destructive circumstances. Specifically, it has played a significant role in describing the conditions of depression, trauma-related disorders, anxiety, detachment at school, workplace burnout, and the psychological effects of chronic abuse or neglect over time.

Therapeutic Approach

As a therapeutic approach, this one emphasizes the fact that helplessness is not a genetic characteristic, but rather a learned behavior as a result of constant loss of control. Thus, and last, but not least, it points out that helplessness is something that can be reversed and taught out with the help of supportive interventions, empowering ones, and skill-based interventions.

It thus also highlights that helplessness can be learnt out by the use of supportive, empowering, and skills based intervention.

Origin of Learned Helplessness Theory

The theory was first proposed by Martin Seligman in the late 1960s, based on experimental research examining how animals and humans respond to situations where outcomes appear independent of their behavior.

Seligman’s work challenged the assumption that individuals always learn to act in their best interest.

The Classic Experiments

In the original experiments, dogs were repeatedly exposed to unavoidable electric shocks in situations where no escape was possible. At first, the animals were in distress and were trying to escape the shocks. But with time, they even ceased to make any attempts. Subsequently, dogs that were put in a different environment where escape appeared to be evident, did not take the initiative to escape even when that meant very little effort.

Key Observations

-

First, the dogs had learned that their actions were ineffective in influencing outcomes.

-

Second, this learning generalized to new situations, even when those situations were controllable.

-

Consequently, passivity gradually replaced active problem-solving behavior.

This pattern of learned passivity and expectation of failure became known as learned helplessness.

⚠️ Importantly, the dogs were not physically incapable of escaping. Rather, they were psychologically conditioned to expect failure, which prevented them from taking action.

Core Assumptions of Learned Helplessness Theory

Based on these findings, the Learned Helplessness Theory rests on three fundamental assumptions that explain how helplessness develops and persists.

1. Perceived Lack of Control

When individuals are repeatedly exposed to situations in which outcomes appear independent of their efforts, they begin to develop a belief that they have no control over what happens. Over time, this leads to the expectation:

“Nothing I do will change the result.”

As a result, motivation decreases and effort feels meaningless.

2. Generalization of Helplessness

Importantly, this belief does not remain confined to the original situation. Instead, it spreads to other areas of life, even when control and choice are actually available. For example, a person who feels helpless in one domain may begin to feel ineffective in relationships, work, or academics.

3. Expectancy of Failure

Finally, individuals begin to anticipate negative outcomes before taking action. Consequently, they experience reduced motivation, emotional distress, and impaired cognitive functioning. Problem-solving becomes more difficult, and avoidance often replaces effort.

Key Insight

Together, these assumptions explain why learned helplessness is not a lack of ability, but a learned belief system shaped by repeated experiences of uncontrollability. Therefore, understanding this process is essential for reversing helplessness and restoring a sense of agency.

The Three Components of Learned Helplessness

Learned helplessness affects individuals on motivational, cognitive, and emotional levels. Together, these components explain why people stop trying, struggle to think clearly, and experience deep emotional distress, even when change is possible.

1. Motivational Deficits

First and foremost, learned helplessness leads to significant motivational deficits. Individuals show a noticeable reduction in effort and initiative, often giving up quickly when faced with obstacles. Over time, challenges begin to feel overwhelming, and avoidance replaces active engagement.

-

Reduced effort and initiative

-

Giving up easily

-

Avoidance of challenges

As a result, individuals stop trying—not because they lack ability, but because effort feels pointless. Repeated experiences of failure teach them that action will not lead to improvement, weakening motivation further.

2. Cognitive Deficits

In addition to motivational changes, learned helplessness produces cognitive impairments that affect how individuals think, interpret situations, and solve problems. People may struggle to learn new responses or adapt to changing circumstances, even when solutions are available.

-

Difficulty learning new responses

-

Impaired problem-solving abilities

-

Persistent negative self-beliefs

Common thought patterns include:

-

“I’m incapable.”

-

“There’s no solution.”

-

“I always fail.”

Consequently, these distorted beliefs reinforce helplessness by convincing individuals that success is unattainable, further reducing effort and flexibility in thinking.

3. Emotional Deficits

Finally, learned helplessness is accompanied by profound emotional deficits. Persistent feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and anxiety often emerge. In some cases, individuals may also experience emotional numbness, where they feel disconnected from both positive and negative emotions.

-

Sadness and hopelessness

-

Anxiety and emotional numbness

-

Low self-worth and self-esteem

Importantly, these emotional responses closely resemble clinical depression, which explains why learned helplessness is strongly associated with depressive disorders and trauma-related conditions.

Integrative Insight

Taken together, these three components form a self-reinforcing cycle. Reduced motivation limits action, distorted thinking undermines confidence, and emotional distress deepens withdrawal. Therefore, effective intervention must address all three levels—restoring motivation, challenging cognitive distortions, and supporting emotional healing.

Learned Helplessness and Depression

Learned helplessness became a cornerstone in psychological explanations of depression. Many depressive symptoms—such as hopelessness, withdrawal, and low motivation—can be understood as consequences of perceived uncontrollability.

Later refinements introduced the concept of attributional style:

-

Internal (“It’s my fault”)

-

Stable (“It will never change”)

-

Global (“It affects everything”)

This pattern is especially linked to chronic depression.

Learned Helplessness in Real Life

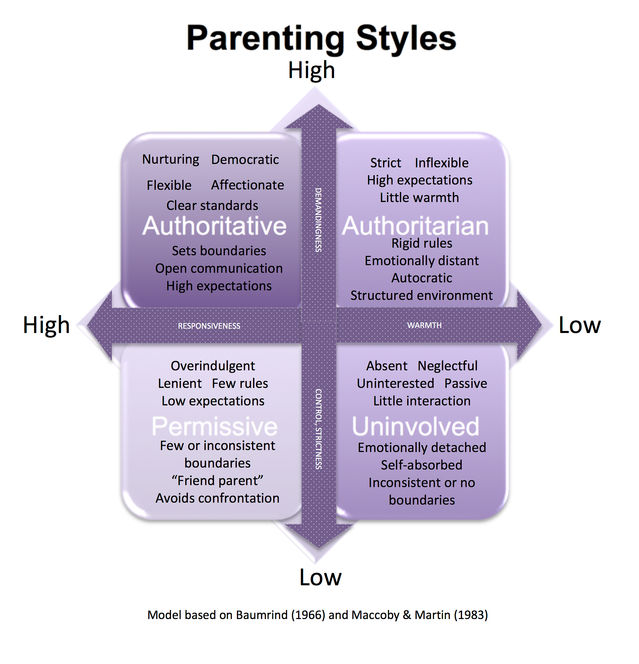

1. Childhood and Parenting

-

Harsh criticism

-

Inconsistent discipline

-

Emotional or physical abuse

Children may learn that effort does not lead to safety or approval, shaping lifelong patterns of helplessness.

2. Education

Students who repeatedly fail despite effort may conclude:

“I’m bad at studying.”

This can lead to academic disengagement, not lack of ability.

3. Relationships

In abusive or controlling relationships, individuals may feel:

-

Trapped

-

Powerless

-

Unable to leave or seek help

Even when support becomes available, action feels impossible.

4. Workplace

-

Chronic micromanagement

-

Unfair evaluations

-

Lack of recognition

Employees may disengage, showing burnout and resignation rather than motivation.

Learned Helplessness and Trauma

Trauma—especially chronic or interpersonal trauma—strongly reinforces learned helplessness. When escape or resistance repeatedly fails, the nervous system adapts by shutting down effort as a survival strategy.

This explains why trauma survivors may:

-

Freeze instead of act

-

Struggle with decision-making

-

Feel powerless long after danger has passed

From Learned Helplessness to Learned Hopefulness

Later research, including Seligman’s own work, emphasized that helplessness is learned—and therefore unlearnable.

Key Interventions:

-

Restoring a sense of control

-

Teaching problem-solving skills

-

Challenging negative attributional styles

-

Encouraging small, successful actions

This shift led to the concept of learned optimism.

Therapeutic Implications

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

-

Identifies helpless beliefs

-

Challenges distorted attributions

-

Builds mastery experiences

Trauma-Informed Therapy

-

Emphasizes safety and choice

-

Avoids re-creating powerlessness

-

Respects the pace of the client

Counseling and Education

-

Reinforces effort–outcome connections

-

Focuses on strengths and agency

-

Uses gradual exposure to success

Strengths of the Theory

-

Explains passivity in depression and trauma

-

Strong empirical foundation

-

Practical applications in therapy, education, and social policy

Limitations of the Theory

-

Early animal research raised ethical concerns

-

Does not fully account for resilience

-

Overemphasis on cognition may underplay biological factors

Conclusion

The Learned Helplessness Theory reveals a powerful psychological truth:

When people learn that their actions don’t matter, they stop acting—even when change is possible.

Understanding learned helplessness allows psychologists, counselors, educators, and caregivers to replace resignation with agency, helplessness with hope, and passivity with empowerment.

Healing begins not with forcing action—but by restoring belief in control.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is Learned Helplessness Theory?

Learned Helplessness Theory explains how repeated exposure to uncontrollable and unavoidable negative experiences leads individuals to believe that their actions no longer influence outcomes, resulting in passivity and withdrawal.

2. Who proposed the Learned Helplessness Theory?

The theory was proposed by psychologist Martin E. Seligman, based on experimental research conducted in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

3. How does learned helplessness develop?

Learned helplessness develops when repeated failures or uncontrollable events teach individuals that effort does not lead to success, causing them to stop trying even when change is possible.

4. What are the main components of learned helplessness?

Learned helplessness involves three key components:

-

Motivational deficits (reduced effort and initiative)

-

Cognitive deficits (negative beliefs and poor problem-solving)

-

Emotional deficits (sadness, anxiety, hopelessness)

5. How is learned helplessness related to depression?

Learned helplessness is closely linked to depression because both involve hopelessness, passivity, low motivation, and negative thinking patterns, especially when individuals feel powerless over life events.

6. Can learned helplessness affect children and students?

Yes. In educational settings, repeated academic failure or harsh criticism can cause students to believe they are incapable, leading to academic disengagement and avoidance of challenges.

7. How does trauma contribute to learned helplessness?

Chronic trauma, abuse, or neglect often involves repeated loss of control, which reinforces helplessness and explains why trauma survivors may feel stuck, powerless, or unable to act, even after the threat has passed.

8. Is learned helplessness permanent?

No. Learned helplessness is not an inherent trait. Because it is learned, it can also be unlearned through therapy, supportive environments, skill-building, and experiences that restore a sense of control.

9. How is learned helplessness treated in therapy?

Therapeutic approaches such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and trauma-informed counseling help individuals challenge helpless beliefs, rebuild confidence, and reconnect effort with positive outcomes.

10. Why is Learned Helplessness Theory important?

The theory helps explain why people remain stuck in harmful situations and provides a foundation for interventions aimed at restoring agency, motivation, and psychological resilience.

Written by Baishakhi Das

Counselor | Mental Health Practitioner

B.Sc, M.Sc, PG Diploma in Counseling

Reference

-

American Psychological Association – Learned Helplessness

https://dictionary.apa.org/learned-helplessness -

Simply Psychology – Learned Helplessness

https://www.simplypsychology.org/learned-helplessness.html -

Seligman, M. E. P. (1975). Helplessness: On Depression, Development, and Death

https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1976-21548-000 -

Verywell Mind – Learned Helplessness Explained

https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-learned-helplessness-2795326 -

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) – Depression Overview

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/depression -

World Health Organization – Mental Health and Trauma

https://www.who.int/teams/mental-health-and-substance-use - Cognitive Behavioral Theory: How Thoughts Control Emotions