What Is Parentification?

Parentification happens when caregivers place a child in a parental role—emotionally, practically, or both. Instead of receiving consistent care, protection, and guidance, the child takes responsibility for meeting the emotional, physical, or psychological needs of adults or siblings. This role reversal pushes the child to mature prematurely and often disrupts their emotional development.

Family systems theorist Ivan Boszormenyi-Nagy introduced the concept, explaining how disrupted family roles and emotional imbalance interfere with healthy attachment, identity formation, and self-worth. When adults expect a child to function as a caregiver, the child loses the safety of dependence—even though dependence forms a core developmental need in childhood.

It’s important to understand that parentification is not about occasional help or learning responsibility. Helping with chores, caring for a sibling briefly, or supporting a parent during a short-term crisis can be part of healthy development when adequate support and boundaries exist.

Parentification becomes traumatic when:

-

The responsibility is chronic and ongoing, not temporary

-

The child’s emotional needs are consistently ignored or minimized

-

The role is developmentally inappropriate for the child’s age

-

There is no reliable adult backup, guidance, or emotional safety

In these situations, the child learns that their value lies in being useful, mature, or emotionally strong—rather than being cared for. Over time, this shapes how they see themselves, relationships, and their right to rest, need, or vulnerability.

Parentification is not a character flaw or strength—it is an adaptive response to unmet needs.

Types of Parentification

1. Emotional Parentification

The child becomes the emotional support system for the parent.

Examples:

-

Listening to a parent’s marital problems

-

Regulating a parent’s emotions

-

Acting as a confidant, mediator, or therapist

-

Feeling responsible for a parent’s happiness

2. Instrumental Parentification

The child takes on adult-level practical responsibilities.

Examples:

-

Caring for siblings daily

-

Managing finances, cooking, or household duties

-

Acting as a substitute spouse or co-parent

-

Making adult decisions too early

Both forms often coexist and reinforce each other.

Why Parentification Is Traumatic

Children are not neurologically, emotionally, or psychologically equipped to carry adult responsibilities. Their brains and nervous systems are still developing, and they rely on caregivers for regulation, safety, and guidance. When a child is forced into an adult role, their nervous system shifts into survival mode—prioritizing vigilance, control, and emotional containment over healthy growth and exploration.

Instead of learning who they are, the child learns how to manage others. Instead of feeling safe enough to express emotions, they learn to suppress them. This adaptation may help the child cope in the moment—but it comes at a long-term psychological cost.

Over time, parentification can lead to:

-

Chronic hypervigilance

Constantly scanning for others’ moods, needs, or potential conflict -

Emotional suppression

Learning that feelings are inconvenient, unsafe, or secondary -

Difficulty identifying personal needs

Feeling disconnected from one’s own desires, limits, and bodily signals -

A belief that love must be earned through usefulness

Equating worth with responsibility, sacrifice, or emotional labor

Because these patterns often look like maturity, competence, or strength from the outside, they are frequently misunderstood and even praised. But beneath the surface, the child was never given the freedom to be vulnerable, dependent, or cared for.

This is not resilience.

This is adaptive survival—a child doing whatever was necessary to stay emotionally safe in an unsafe environment.

Signs You Grew Up Too Fast (Adult Indicators)

1. You Feel Responsible for Everyone

You automatically take care of others, even at your own expense. Rest feels uncomfortable or undeserved.

2. You Struggle to Identify Your Own Needs

When asked, “What do you want?”—your mind goes blank or you feel anxious.

3. You’re Emotionally Mature but Deeply Exhausted

You’re “strong,” “wise,” and “reliable,” yet internally burned out.

4. You Fear Burdening Others

You avoid asking for help because you learned early that your needs were secondary.

5. You Feel Guilty When You Rest or Say No

Boundaries trigger guilt, anxiety, or fear of rejection.

6. You Were “The Good Child”

You were praised for being understanding, independent, or low-maintenance—but never truly seen.

7. You Attract One-Sided Relationships

You often become the caretaker, fixer, or emotional anchor in friendships and romantic relationships.

8. You Feel Older Than Your Age—Or Younger Inside

You may appear highly responsible externally while feeling emotionally stuck, playful, or deprived internally.

Parentification vs Healthy Responsibility

| Healthy Responsibility | Parentification |

|---|---|

| Age-appropriate tasks | Adult-level roles |

| Choice and flexibility | Obligation and pressure |

| Emotional support available | Emotional neglect |

| Child’s needs prioritized | Child’s needs ignored |

The key difference is choice, balance, and emotional safety.

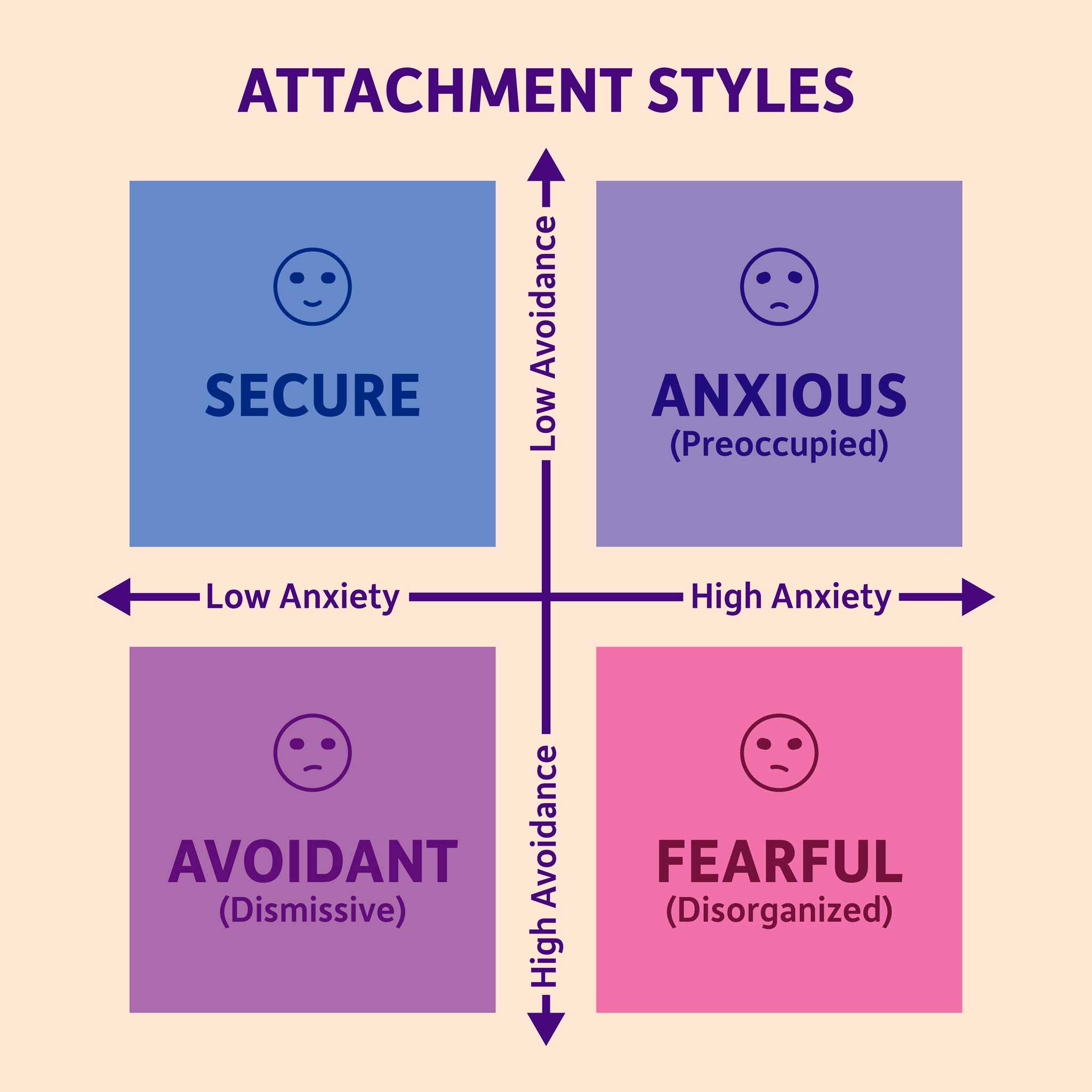

Long-Term Psychological Effects

Untreated parentification trauma may contribute to:

-

Anxiety and chronic stress

-

Depression and emotional numbness

-

Codependency

-

Burnout and compassion fatigue

-

Difficulty with intimacy

-

Perfectionism

-

Suppressed anger and resentment

Many adults only recognize the impact later in life—often after emotional collapse, relationship difficulties, or burnout.

Why Parentification Often Goes Unrecognized

Parentification is frequently overlooked and misunderstood, because its effects often appear positive on the surface. In many families and cultures, the behaviors created by parentification are not only accepted—but actively encouraged.

Parentification is frequently:

-

Praised as maturity

The child is labeled “wise beyond their years,” “responsible,” or “so strong,” reinforcing the idea that their premature adulthood is a virtue rather than a burden. -

Normalized in families under stress

In households affected by illness, poverty, addiction, conflict, or single parenting, role reversal is often seen as necessary for survival—making the child’s sacrifice invisible. -

Culturally reinforced (especially in caregiving roles)

In many cultures, children—particularly eldest daughters—are expected to care, adjust, and emotionally accommodate, blurring the line between responsibility and emotional neglect. -

Hidden behind success or competence

Many parentified children grow into high-functioning adults: reliable, high-achieving, and outwardly “fine.” Their internal exhaustion is rarely questioned.

Because the child functioned well, no one asked whether they were hurting.

Because they didn’t fall apart, their unmet needs were overlooked.

The absence of visible dysfunction does not mean the absence of trauma—it often means the child learned to survive quietly.

Healing From Parentification Trauma

Healing does not mean blaming caregivers—it means reclaiming your unmet childhood needs.

Key Steps Toward Healing

1. Name the Experience

Understanding that this was not your responsibility is the first step.

2. Allow Grief

Grieve the childhood you didn’t receive. This grief is valid.

3. Learn to Identify Needs

Start small: What do I feel? What do I need right now?

4. Practice Boundaries Without Guilt

Boundaries are not rejection—they are self-respect.

5. Reparent Yourself

Offer yourself the care, safety, and permission you never had.

6. Seek Trauma-Informed Therapy

A trained mental health professional can help process role reversal, suppressed emotions, and attachment wounds safely.

A Compassionate Reminder

If you were parentified, you were not “too sensitive,” “too serious,” or “too responsible.”

You were a child who adapted to survive.

Growing up too fast may have kept you safe then—but healing allows you to finally live, rest, and receive now.

Care is not something you have to deserve.

Strength does not mean doing it all alone.

You were always worthy of support, rest, and protection.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Is parentification always abusive?

Not always intentionally abusive, but it can still be psychologically harmful. Even when parents are overwhelmed rather than malicious, chronic role reversal can disrupt a child’s emotional development.

2. What is the difference between responsibility and parentification?

Healthy responsibility is age-appropriate, temporary, and supported by adults. Parentification is ongoing, emotionally demanding, and places adult-level expectations on a child without adequate support.

3. Can parentification affect adulthood?

Yes. Adults who were parentified often struggle with boundaries, people-pleasing, burnout, anxiety, emotional numbness, and difficulty asking for help.

4. Why do parentified children often become “high achievers”?

Because their nervous system learned that safety and love come from performance, usefulness, and reliability—not from simply being themselves.

5. Can parentification trauma be healed?

Yes. With awareness, boundary work, self-compassion, and trauma-informed therapy, individuals can reconnect with their needs and heal attachment wounds.

6. Is parentification common in certain cultures?

Yes. In many collectivist or caregiving-focused cultures, emotional and instrumental parentification—especially of eldest children or daughters—is often normalized.

Written by Baishakhi Das

Counselor | Mental Health Practitioner

B.Sc, M.Sc, PG Diploma in Counseling

Reference

-

American Psychological Association – Childhood Stress & Trauma

https://www.apa.org/topics/trauma -

National Institute of Mental Health – Trauma and Stress-Related Disorders

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd -

Boszormenyi-Nagy, I., & Spark, G. (1973). Invisible Loyalties

https://www.routledge.com/Invisible-Loyalties -

van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/220644/ -

Minuchin, S. (1974). Families and Family Therapy

https://www.hup.harvard.edu/books/9780674292368 - How Childhood Emotional Neglect Affects Adults