Jean Piaget’s Theory of Moral Development (Expanded Explanation)

Jean Piaget viewed moral development as a natural outcome of cognitive development. He believed that children are not born with an understanding of morality, nor do they simply absorb moral rules from adults. Instead, children are active thinkers who construct their moral understanding through interaction with their environment and with others. As children’s thinking becomes more sophisticated, their moral reasoning also becomes more flexible and mature.

Piaget emphasized that morality evolves alongside a child’s ability to think logically, take perspectives, and understand intentions. This means that moral development is developmental, not merely the result of discipline or instruction.

Core Assumptions of Piaget’s Theory

Piaget’s theory rests on several key ideas:

-

Morality develops through social interaction, particularly with peers rather than adults. Peer relationships allow children to negotiate, cooperate, and experience fairness.

-

Children gradually move from rule acceptance to rule negotiation, learning that rules are created by people and can be modified.

-

Cognitive maturity plays a central role in moral reasoning; children’s judgments depend on how they think, not just on fear of punishment.

-

Moral understanding shifts from an external authority-based system to an internal, reasoned system.

Based on these assumptions, Piaget identified two major stages of moral development.

Stage 1: Heteronomous Morality (Moral Realism)

Age Range: Approximately 4–7 years

In this early stage, children view morality as externally controlled.

Key Characteristics

-

Rules are seen as fixed, absolute, and unchangeable

-

Authority figures such as parents, teachers, or elders define what is right and wrong

-

Moral judgment is based on consequences, not intentions

-

Punishment is perceived as automatic and unavoidable (“If you do something wrong, you will be punished”)

Example

A child believes:

“Breaking five cups by accident is worse than breaking one cup on purpose.”

Here, the child focuses on the amount of damage rather than the intention behind the action.

Psychological Insight

This stage reflects egocentric thinking. Children are limited in their ability to take another person’s perspective and therefore struggle to understand intentions, motives, or situational factors.

Stage 2: Autonomous Morality (Moral Relativism)

Age Range: Around 8–12 years and beyond

As children grow cognitively and socially, they enter a more advanced form of moral reasoning.

Key Characteristics

-

Rules are understood as social agreements, not absolute laws

-

Intentions matter more than outcomes

-

Concepts of fairness, equality, and reciprocity become important

-

Children recognize that rules can be changed through mutual consent

-

Moral judgments become more flexible and context-sensitive

Example

A child believes:

“Breaking one cup on purpose is worse than breaking five accidentally.”

This reflects an understanding that intention is more important than the physical outcome.

Psychological Insight

Autonomous morality develops largely through peer interaction, where children experience cooperation, conflict resolution, and shared decision-making rather than one-sided authority.

Strengths of Piaget’s Theory

-

First systematic and scientific study of children’s moral reasoning

-

Highlighted the importance of intentions in moral judgment

-

Emphasized the crucial role of peer relationships in moral development

-

Shifted the view of children from passive learners to active moral thinkers

Limitations of Piaget’s Theory

-

Focused mainly on childhood, offering limited insight into adult moral development

-

Based on small and homogeneous samples

-

Underestimated younger children’s ability to show moral understanding

-

Did not fully account for emotional, cultural, or contextual influences on morality

Why Piaget’s Theory Still Matters

Despite its limitations, Piaget’s work laid the foundation for modern moral development theories, particularly influencing later theorists like Kohlberg. His central idea—that morality grows through thinking, interaction, and experience—remains a cornerstone in psychology, education, and child counseling.

Lawrence Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development

Lawrence Kohlberg expanded on Jean Piaget’s foundational ideas and proposed that moral reasoning develops through six distinct stages, organized into three hierarchical levels. Unlike Piaget, who focused mainly on childhood, Kohlberg argued that moral development is a lifelong process that can continue into adulthood, although not everyone reaches the highest stages.

Kohlberg’s theory places emphasis on moral reasoning rather than moral behavior. He was less interested in whether a person’s decision was “right” or “wrong” and more concerned with the reasoning used to justify that decision. According to Kohlberg, two people might make the same moral choice but be operating at very different levels of moral development, depending on whether their reasoning is based on fear of punishment, social approval, obedience to law, or internal ethical principles.

To study moral reasoning, Kohlberg used moral dilemmas, most famously the Heinz dilemma, where individuals were asked to explain what a person should do and, more importantly, why. The justification revealed the individual’s stage of moral development. This approach highlighted that moral growth involves a gradual shift from externally controlled reasoning (punishment and authority) to internally guided principles such as justice, rights, and human dignity.

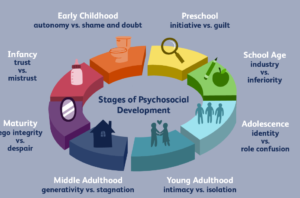

Kohlberg’s Three Levels & Six Stages

Lawrence Kohlberg proposed that moral reasoning develops through three levels, each consisting of two stages. These stages represent increasingly complex ways of thinking about moral issues. Progression through the stages depends on cognitive growth, social experiences, and exposure to moral dilemmas, and not everyone reaches the highest levels.

Level 1: Preconventional Morality

Typical Age: Childhood

At this level, morality is externally controlled. Children understand right and wrong based on personal consequences, not social rules or ethical principles.

Stage 1: Obedience and Punishment Orientation

In the earliest stage, behavior is guided by the desire to avoid punishment.

Key Features

-

Authority figures are seen as all-powerful

-

Rules are fixed and unquestioned

-

Moral decisions are based on fear of consequences

Example

“Stealing is wrong because you’ll go to jail.”

Psychological Insight

Moral reasoning is egocentric and consequence-focused, similar to Piaget’s heteronomous morality.

Stage 2: Self-Interest Orientation

At this stage, children begin to recognize that others also have needs, but morality is still self-centered.

Key Features

-

Right action is what benefits oneself

-

Moral decisions are transactional (“You help me, I help you”)

-

Fairness is understood as equal exchange, not empathy

Example

“Heinz should steal the drug because he needs his wife.”

Psychological Insight

This stage reflects a pragmatic view of morality driven by personal gain rather than social norms.

Level 2: Conventional Morality

Typical Age: Adolescence to adulthood

Here, individuals internalize social norms and expectations. Morality is defined by the desire to maintain relationships and social order.

Stage 3: Good Boy / Good Girl Orientation

Key Features

-

Strong desire for social approval

-

Being “good” means meeting others’ expectations

-

Intentions and emotions begin to matter

Example

“People will think Heinz is a good husband.”

Psychological Insight

Moral behavior is motivated by empathy and the need to belong, rather than fear of punishment.

Stage 4: Law and Order Orientation

Key Features

-

Emphasis on law, authority, and duty

-

Rules are necessary to maintain social order

-

Moral reasoning extends beyond close relationships to society as a whole

Example

“If everyone steals, society will collapse.”

Psychological Insight

This stage reflects respect for institutions and the belief that laws must be obeyed to prevent chaos.

Level 3: Postconventional Morality

Typical Age: Adulthood (not all individuals reach this level)

At this highest level, morality is guided by internalized ethical principles, which may sometimes conflict with laws or social norms.

Stage 5: Social Contract Orientation

Key Features

-

Laws are viewed as social agreements

-

Emphasis on individual rights and democratic values

-

Rules can be changed if they no longer serve the greater good

Example

“Life is more important than property.”

Psychological Insight

Moral reasoning balances societal rules with human rights and ethical considerations.

Stage 6: Universal Ethical Principles

Key Features

-

Morality is based on self-chosen ethical principles

-

Principles such as justice, dignity, and equality guide decisions

-

Willingness to act according to conscience, even at personal cost

Example

“Human life must be protected regardless of law.”

Psychological Insight

This stage represents ideal moral reasoning, though very few people consistently operate at this level.

Strengths of Kohlberg’s Theory

-

Explains moral reasoning across the lifespan

-

Provides a clear, structured framework for understanding moral growth

-

Widely applied in education, ethics, law, and psychology

-

Emphasizes reasoning over blind rule-following

Limitations of Kohlberg’s Theory

-

Cultural bias toward Western, individualistic values

-

Overemphasis on justice-based reasoning, neglecting care, empathy, and emotion

-

Moral reasoning does not always translate into moral behavior

-

Many individuals function at different stages depending on context

Summary Insight

Kohlberg’s theory shows that moral development is a journey from self-interest to social responsibility to ethical principles. It highlights that morality is not static but evolves through reflection, experience, and increasing cognitive complexity.

Piaget vs Kohlberg: Key Differences

| Aspect | Piaget | Kohlberg |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Children’s moral thinking | Lifespan moral reasoning |

| Stages | 2 stages | 6 stages |

| Key Factor | Cognitive development | Moral reasoning structure |

| Role of Authority | Strong in early stages | Gradually replaced by principles |

| Method | Observation & interviews | Moral dilemmas |

How Piaget and Kohlberg’s Theories Complement Each Other

Jean Piaget and Lawrence Kohlberg did not offer competing explanations of moral development; instead, their theories build upon one another, creating a more complete picture of how morality develops across the lifespan.

Piaget explains how moral understanding begins. His work focuses on early childhood and shows how children initially view rules as fixed and externally imposed, and gradually come to understand intentions, fairness, and mutual respect through cognitive growth and peer interaction. In this sense, Piaget identifies the origins of moral thinking, highlighting how basic moral concepts emerge alongside cognitive development.

Kohlberg takes these foundational ideas further by explaining how moral reasoning becomes more complex over time. Extending beyond childhood into adolescence and adulthood, Kohlberg demonstrates how individuals move from consequence-based reasoning to socially oriented thinking and, in some cases, to abstract ethical principles. His theory maps the progression and refinement of moral reasoning across different life stages.

Together, their theories show that morality is not a fixed trait or a set of rules learned once in childhood. Instead, morality is a dynamic, developmental process shaped by cognitive maturity, social relationships, and moral reflection. Piaget provides the roots—the early formation of moral understanding—while Kohlberg provides the branches, illustrating how that understanding expands, differentiates, and becomes principled over time.

Modern Psychological Perspective

Contemporary psychology recognizes that:

-

Emotion, empathy, and culture shape morality

-

Moral reasoning does not always predict behavior

-

Context matters (stress, trauma, social pressure)

Later theories (e.g., care-based ethics, social intuitionism) expand beyond strict stage models.

Conclusion

Piaget and Kohlberg transformed our understanding of moral development.

Piaget showed us how children begin to think morally, while Kohlberg demonstrated how moral reasoning can evolve into principled thinking.

Together, their theories remind us that morality is not taught—it is constructed, questioned, and refined over time.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ): Moral Development – Piaget & Kohlberg

1. What is moral development?

Moral development refers to the process by which individuals learn to distinguish right from wrong, develop moral values, and reason about ethical issues. It focuses on how people think about moral problems, not just how they behave.

2. How did Jean Piaget explain moral development?

Jean Piaget explained moral development as part of cognitive development. He believed children actively construct moral understanding through interaction with peers and their environment. According to Piaget, children move from seeing rules as fixed and authority-driven to understanding them as flexible social agreements based on intentions and fairness.

3. How is Kohlberg’s theory different from Piaget’s?

Lawrence Kohlberg expanded Piaget’s work by proposing a six-stage, lifespan model of moral development. While Piaget focused mainly on childhood, Kohlberg explained how moral reasoning can continue to evolve into adulthood. Kohlberg emphasized justifications for moral decisions, not the decisions themselves.

4. What are the three levels of Kohlberg’s moral development?

Kohlberg proposed three levels:

-

Preconventional – morality based on punishment and self-interest

-

Conventional – morality based on social approval and law

-

Postconventional – morality based on ethical principles and human rights

Each level contains two stages, making six stages in total.

5. Do all people reach the highest stage of moral development?

No. Kohlberg believed that not everyone reaches postconventional morality. Many adults function primarily at the conventional level, where maintaining social order and following laws are central.

6. Why is Kohlberg’s theory criticized?

Common criticisms include:

-

Cultural bias toward Western, justice-oriented values

-

Overemphasis on reasoning over emotion and care

-

Moral reasoning does not always predict moral behavior

Later theories (e.g., care ethics) addressed these gaps.

7. How do Piaget and Kohlberg’s theories complement each other?

Piaget explains how moral understanding begins in childhood, while Kohlberg explains how moral reasoning becomes more complex over time. Together, they show morality as a developmental process, not a fixed trait—Piaget provides the foundation, and Kohlberg maps its expansion.

8. Why are these theories important in psychology and education?

These theories help:

-

Teachers understand children’s moral reasoning

-

Counselors assess ethical thinking and decision-making

-

Psychologists study moral judgment across development

-

Parents guide discipline using age-appropriate reasoning

Written by Baishakhi Das

Counselor | Mental Health Practitioner

Qualifications: B.Sc in Psychology | M.Sc | PG Diploma in Counseling

Reference Links (Authoritative Sources)

-

American Psychological Association – Moral Development

https://www.apa.org/monitor/nov01/moral -

Simply Psychology – Piaget’s Moral Development

https://www.simplypsychology.org/piaget-moral-development.html -

Simply Psychology – Kohlberg’s Moral Development Theory

https://www.simplypsychology.org/kohlberg.html -

McLeod, S. (2023). Moral Development. Simply Psychology

https://www.simplypsychology.org/moral-development.html -

Kohlberg, L. (1981). Essays on Moral Development, Vol. 1: The Philosophy of Moral Development. Harper & Row

https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1981-20178-000 -

Piaget, J. (1932). The Moral Judgment of the Child. Routledge

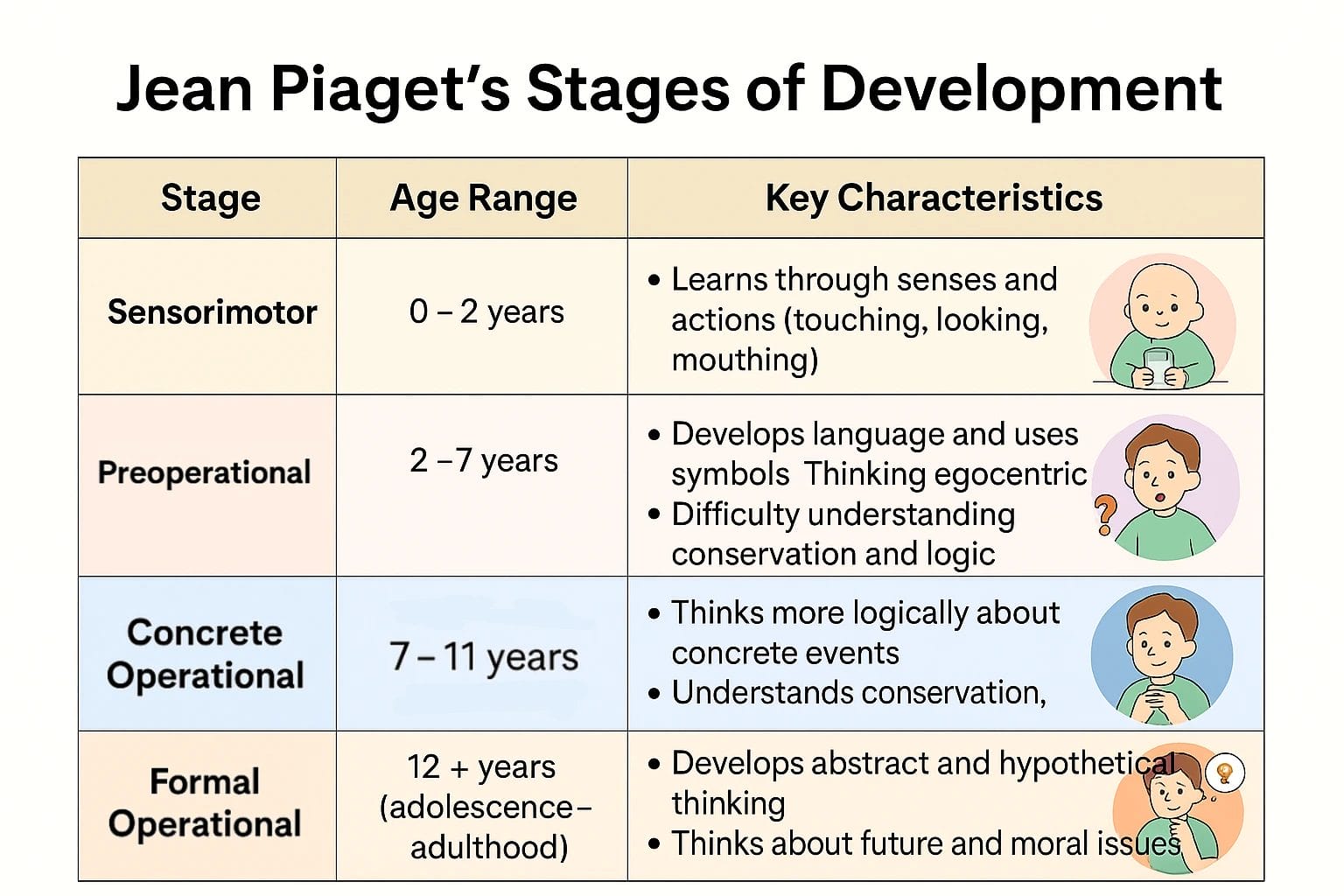

https://archive.org/details/moraljudgmentofc0000piag - Piaget’s Cognitive Development Theory