Introduction: When Exhaustion Goes Beyond Tiredness

Everyone feels tired sometimes. Long days, responsibilities, emotional demands, and stress are part of modern life. But emotional burnout is different. It is not solved by a weekend off, a good night’s sleep, or a short break.

Emotional burnout is a state of chronic emotional, mental, and physical exhaustion caused by prolonged stress—especially stress that feels inescapable, unrecognized, or unsupported. It slowly drains motivation, empathy, and a sense of meaning, often without dramatic warning signs.

Many people ignore burnout because they believe:

-

“This is just stress.”

-

“I should be able to handle this.”

-

“Others have it worse.”

-

“Once things settle down, I’ll feel better.”

But burnout does not suddenly appear—it builds quietly. And the longer it goes unnoticed, the deeper its impact on mental health, relationships, and physical well-being.

This article explores what emotional burnout really is, how it develops, the symptoms you should never ignore, and how recovery is possible.

What Is Emotional Burnout?

Emotional burnout is a condition marked by persistent emotional depletion, reduced capacity to cope, and a sense of detachment or hopelessness. It occurs when emotional demands consistently exceed a person’s internal and external resources.

Burnout commonly affects:

-

Caregivers

-

Parents

-

Healthcare professionals

-

Counselors and teachers

-

Corporate employees

-

Homemakers

-

Individuals in emotionally demanding relationships

However, burnout is not limited to work—it can arise from chronic family conflict, financial stress, caregiving roles, trauma, or prolonged emotional suppression.

Burnout vs Stress: Understanding the Difference

Stress involves too much pressure.

Burnout involves nothing left to give.

| Stress | Burnout |

|---|---|

| Over-engagement | Emotional disengagement |

| Anxiety and urgency | Hopelessness and numbness |

| Feeling overwhelmed | Feeling empty |

| Still motivated | Loss of motivation |

| Temporary | Chronic |

Stress says, “I can’t keep up.”

Burnout says, “I don’t care anymore.”

How Emotional Burnout Develops

Burnout is rarely sudden. It develops in stages, often unnoticed.

Stage 1: Chronic Overload

-

High expectations

-

Constant responsibility

-

Lack of rest

-

Emotional overextension

Stage 2: Emotional Suppression

-

Ignoring needs

-

“Pushing through”

-

Minimizing feelings

-

Avoiding vulnerability

Stage 3: Depletion

-

Reduced energy

-

Emotional exhaustion

-

Loss of enthusiasm

Stage 4: Detachment

-

Numbness

-

Cynicism

-

Withdrawal from people

Stage 5: Breakdown

-

Anxiety or depressive symptoms

-

Physical illness

-

Emotional shutdown

Recognizing burnout earlier prevents deeper psychological harm.

Emotional Burnout Symptoms You Shouldn’t Ignore

1. Persistent Emotional Exhaustion

You feel drained even after rest. Emotional tasks—listening, caring, responding—feel overwhelming. You may think:

-

“I have nothing left.”

-

“I can’t handle one more thing.”

This exhaustion is emotional, not just physical.

2. Loss of Motivation and Meaning

Tasks that once mattered now feel pointless. You may continue functioning out of obligation, not interest.

Common thoughts:

-

“What’s the point?”

-

“Nothing excites me anymore.”

-

“I’m just going through the motions.”

This loss of meaning is a core burnout signal.

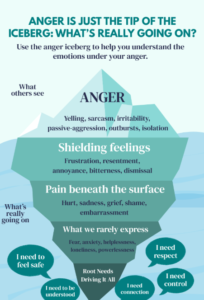

3. Emotional Numbness

Instead of intense feelings, you feel nothing. Happiness, sadness, excitement, and empathy feel distant.

Numbness is not strength—it is a protective shutdown when the nervous system is overwhelmed.

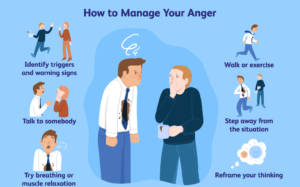

4. Increased Irritability or Detachment

Small things trigger anger or frustration. Alternatively, you may feel emotionally detached and indifferent.

You might:

-

Withdraw from loved ones

-

Avoid conversations

-

Feel guilty for being unavailable

5. Chronic Fatigue

You feel tired all the time, regardless of sleep. Getting through the day feels like an effort.

Burnout fatigue is deep and persistent, not relieved by rest alone.

6. Cognitive Difficulties

Burnout affects thinking:

-

Poor concentration

-

Forgetfulness

-

Indecisiveness

-

Mental fog

You may feel mentally “slow” or ineffective, which further lowers confidence.

7. Physical Symptoms Without Clear Cause

Emotional burnout often manifests physically:

-

Headaches

-

Digestive issues

-

Body aches

-

Weakened immunity

-

Sleep disturbances

The body expresses what the mind has been suppressing.

8. Increased Anxiety or Hopelessness

Burnout can coexist with:

-

Anxiety

-

Low mood

-

Feelings of helplessness

-

Fear of the future

Unchecked burnout may evolve into clinical anxiety or depression.

Emotional Burnout in Different Life Roles

Burnout in the Workplace

-

Feeling undervalued

-

Constant pressure without control

-

Emotional labor without recognition

-

Fear of failure or replacement

High performers are especially vulnerable.

Burnout in Caregivers and Parents

-

Emotional over-responsibility

-

Lack of support

-

No personal time

-

Guilt for needing rest

Caregivers often normalize burnout until collapse occurs.

Burnout in Relationships

-

Constant emotional giving

-

One-sided dynamics

-

Suppressed resentment

-

Fear of conflict

Love does not protect against burnout—lack of boundaries does.

Why Emotional Burnout Is Often Ignored

-

It develops gradually

-

Productivity may remain intact

-

Society rewards overwork

-

Emotional pain is minimized

-

Many confuse burnout with weakness

Ignoring burnout does not make it disappear—it deepens it.

The Psychological Cost of Ignoring Burnout

Untreated burnout can lead to:

-

Anxiety disorders

-

Depression

-

Emotional disconnection

-

Relationship breakdown

-

Identity confusion

-

Loss of self-worth

Burnout does not mean failure—it means you’ve been strong for too long without support.

How Emotional Burnout Affects Identity

Many people tie self-worth to:

-

Productivity

-

Caregiving

-

Achievement

-

Responsibility

Burnout disrupts identity:

“If I can’t function like before, who am I?”

Healing requires redefining worth beyond output.

Recovery from Emotional Burnout: What Actually Helps

1. Acknowledge the Burnout

Naming burnout reduces shame. You are not lazy, weak, or ungrateful—you are exhausted.

2. Reduce Emotional Load (Not Just Tasks)

Burnout is not solved by time management alone. Emotional labor must be addressed.

Ask:

-

What am I emotionally carrying?

-

Where am I over-giving?

-

What boundaries are missing?

3. Rest Without Guilt

True rest is non-productive rest—without self-judgment.

Burnout recovery requires permission to pause.

4. Reconnect with Emotions Safely

Burnout suppresses feelings. Gentle emotional reconnection—through journaling, therapy, or quiet reflection—is essential.

5. Seek Professional Support

Therapy helps:

-

Identify burnout patterns

-

Process suppressed emotions

-

Rebuild boundaries

-

Restore emotional regulation

You do not need to reach crisis to seek help.

When to Seek Help Immediately

Seek professional support if:

-

Burnout lasts more than a few months

-

You feel emotionally numb or hopeless

-

Anxiety or depression symptoms increase

-

Physical health is affected

-

You feel disconnected from yourself or loved ones

Burnout is treatable, especially when addressed early.

Preventing Emotional Burnout Long-Term

-

Set emotional boundaries

-

Normalize asking for help

-

Separate worth from productivity

-

Schedule rest like responsibility

-

Check in with emotions regularly

Prevention is not selfish—it is sustainable care.

Final Thoughts: Burnout Is a Signal, Not a Failure

Emotional burnout is your mind and body asking for care, balance, and recognition. It does not mean you are incapable—it means you have exceeded your emotional capacity without adequate support.

Listening to burnout symptoms early is an act of self-respect.

You deserve rest before collapse.

Support before exhaustion.

Care before breakdown.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ): Emotional Burnout

1. What is emotional burnout?

Emotional burnout is a state of chronic emotional, mental, and physical exhaustion caused by prolonged stress and emotional overload. It develops when demands consistently exceed a person’s capacity to cope, leading to exhaustion, detachment, and loss of motivation.

2. How is emotional burnout different from stress?

Stress involves feeling overwhelmed but still engaged and motivated. Burnout, on the other hand, is marked by emotional depletion, numbness, and disengagement. Stress says, “I have too much to do,” while burnout says, “I have nothing left to give.”

3. What are the early symptoms of emotional burnout?

Early signs include persistent fatigue, irritability, lack of motivation, emotional exhaustion, difficulty concentrating, sleep problems, and feeling detached from work or relationships. Ignoring these signs can lead to more serious mental health concerns.

4. Can emotional burnout affect physical health?

Yes. Emotional burnout often manifests physically through headaches, digestive issues, weakened immunity, muscle pain, sleep disturbances, and chronic fatigue. The body reflects prolonged emotional and psychological stress.

5. Who is most at risk of emotional burnout?

Burnout commonly affects caregivers, parents, healthcare professionals, teachers, counselors, corporate employees, and individuals in emotionally demanding roles or relationships. However, anyone experiencing prolonged stress without adequate support can develop burnout.

6. Is emotional burnout the same as depression?

No, but they can overlap. Burnout is primarily related to chronic stress and emotional overload, while depression is a clinical mood disorder. Untreated burnout can increase the risk of anxiety or depressive disorders over time.

7. Can emotional burnout be prevented?

Yes. Prevention includes setting emotional boundaries, balancing responsibilities, prioritizing rest, seeking social support, and addressing stress early. Regular emotional check-ins and self-care practices reduce the risk significantly.

8. How does therapy help with emotional burnout?

Therapy helps individuals identify burnout patterns, process suppressed emotions, rebuild boundaries, and develop healthier coping strategies. Approaches such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and stress-management interventions are especially effective.

9. When should someone seek professional help for burnout?

You should seek professional help if burnout symptoms persist for weeks or months, interfere with daily functioning, cause emotional numbness or hopelessness, or are accompanied by anxiety, depression, or physical health problems.

Written by Baishakhi Das

Counselor | Mental Health Practitioner

Qualifications: B.Sc in Psychology | M.Sc | PG Diploma in Counseling

Reference

-

World Health Organization – Burnout as an Occupational Phenomenon

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-at-work -

American Psychological Association – Stress and Burnout

https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/burnout -

National Institute of Mental Health – Mental Health Basics

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health -

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Burnout. Annual Review of Psychology

https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033623 -

Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (2009). Burnout: 35 years of research

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/job.595 - Anger Management: Understanding, Regulating, and Transforming Anger in Healthy Ways

- High-Functioning Anxiety: When You Look Fine but Aren’t