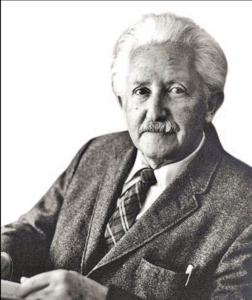

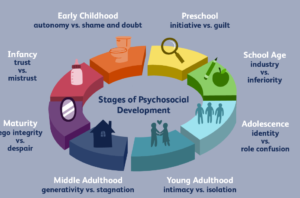

Human development is not limited to childhood—it unfolds across the entire lifespan. One of the most influential frameworks that explains this lifelong growth is Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory of Development, proposed by Erik Erikson.

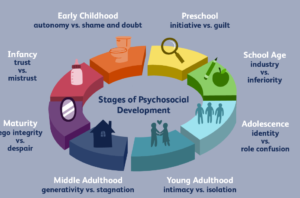

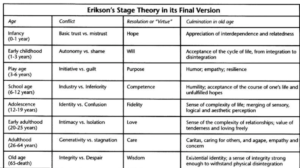

Unlike theories that focus primarily on childhood or biological maturation, Erikson emphasized social relationships, identity, and emotional challenges that individuals face at different stages of life. Each stage presents a psychosocial crisis—a conflict between two opposing forces. How a person resolves these crises shapes personality, emotional health, and relationships throughout life.

This article explores all eight psychosocial stages in depth, explaining their psychological meaning, real-life implications, and relevance in modern mental health practice.

Core Principles of Erikson’s Theory

Life-Span Psychological Development

Erikson was one of the first psychologists to challenge the idea that personality is fully formed in childhood. He proposed that psychological growth continues from birth to old age, with each life phase bringing new challenges, responsibilities, and opportunities for growth.

This means:

- Adults are not “finished products”

- Midlife crises, identity shifts, and late-life reflections are normal

- Change and healing are possible at any age

From a counseling perspective, this principle is deeply hopeful. A person who struggled with trust in childhood or identity in adolescence can still revisit and resolve these conflicts later through insight, supportive relationships, or therapy.

- Social Interaction Is Central

At the heart of Erikson’s theory is the belief that human beings are fundamentally relational. Psychological health is shaped not in isolation, but through interactions with:

- Parents and caregivers

- Peers and teachers

- Romantic partners

- Work environments

- Society and culture

Each psychosocial crisis emerges from the tension between the individual’s inner needs and the social world’s responses. For example:

- Trust develops when caregivers are consistent

- Identity forms through social feedback and belonging

- Intimacy grows through mutual emotional availability

When social environments are invalidating, abusive, neglectful, or overly restrictive, psychosocial development can be disrupted—often showing up later as anxiety, avoidance, people-pleasing, or emotional withdrawal.

- Each Stage Builds on the Previous Ones

Erikson emphasized that development is cumulative, not isolated. Each stage lays a psychological foundation for the next.

For example:

- If trust is not established, independence feels frightening.

- Without autonomy, taking action feels risky.

- Without a clear sense of self, closeness with others feels unsafe.

Unresolved conflicts do not disappear—they often resurface later in disguised forms, such as:

- Relationship difficulties rooted in early mistrust

- Work insecurity tied to childhood inferiority

- Fear of commitment linked to identity confusion

This is why adults sometimes experience intense emotional reactions that seem “out of proportion”—they are often responding from an earlier, unresolved developmental stage.

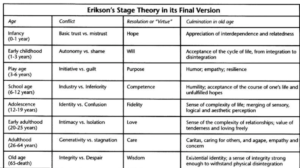

- Healthy Resolution Leads to Psychological Virtues

When a psychosocial crisis is resolved in a healthy way, the individual develops a core psychological strength, which Erikson called a virtue. These virtues are not moral traits, but emotional capacities that support resilience and well-being.

Examples include:

- Hope – belief that life is dependable

- Will – confidence in one’s choices

- Purpose – motivation to pursue goals

- Competence – belief in one’s abilities

- Fidelity – loyalty to one’s identity

- Love – capacity for deep connection

- Care – concern for future generations

- Wisdom – acceptance of life’s meaning

These virtues help individuals navigate stress, loss, transitions, and relationships throughout life.

- Unresolved Crises Do Not Mean Permanent Damage

One of the most compassionate aspects of Erikson’s theory is its non-deterministic nature. Failing to resolve a crisis at the “right” age does not mean lifelong pathology.

Instead:

- It may lead to emotional difficulties

- Identity confusion can emerge during transitions

- Relationship problems may repeat familiar patterns

However, Erikson believed that later life experiences can reopen and repair earlier stages. Supportive relationships, corrective emotional experiences, therapy, and self-awareness allow individuals to:

- Rebuild trust

- Reclaim autonomy

- Redefine identity

- Learn intimacy

This aligns closely with modern trauma-informed and attachment-based therapies.

Why These Foundations Matter Clinically

Understanding these principles helps mental health professionals:

- Normalize clients’ struggles as developmental, not personal failures

- Identify the origin of emotional patterns

- Frame healing as a process, not a fix

- Instill hope that growth remains possible at every life stage

In essence, Erikson’s theory tells us this:

You are not broken—you are still developing.

Your struggles are signals of unfinished developmental work, not signs of weakness.

Stage 1: Trust vs. Mistrust (Infancy | 0–1 year)

Central Question: Can I trust the world?

In infancy, the primary task is developing basic trust. This depends on consistent caregiving—feeding, comfort, warmth, and responsiveness.

Healthy Resolution

- The child feels safe and secure

- Develops confidence that needs will be met

- Leads to the virtue of Hope

Unhealthy Resolution

- Inconsistent or neglectful care creates mistrust

- May lead to anxiety, fear, emotional insecurity

Adult Impact:

Adults with unresolved mistrust may struggle with dependency, intimacy, or constant fear of abandonment.

Stage 2: Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt (Early Childhood | 1–3 years)

Central Question: Can I do things on my own?

As toddlers gain motor and language skills, they seek independence—choosing clothes, feeding themselves, saying “no.”

Healthy Resolution

- Encouragement supports autonomy

- Child develops confidence and self-control

- Leads to the virtue of Will

Unhealthy Resolution

- Overly critical or controlling parenting creates shame

- Child doubts abilities and fears mistakes

Adult Impact:

May appear as low self-esteem, perfectionism, or fear of making decisions.

Stage 3: Initiative vs. Guilt (Preschool | 3–6 years)

Central Question: Is it okay for me to want and do things?

Children begin planning activities, playing roles, and asserting power over their environment.

Healthy Resolution

- Initiative is encouraged

- Child learns leadership and imagination

- Leads to the virtue of Purpose

Unhealthy Resolution

- Excessive punishment or criticism creates guilt

- Child suppresses curiosity and ambition

Adult Impact:

Chronic guilt, difficulty asserting needs, fear of taking initiative.

Stage 4: Industry vs. Inferiority (School Age | 6–12 years)

Central Question: Am I competent and capable?

School introduces structured learning, comparison with peers, and achievement.

Healthy Resolution

- Recognition of effort builds competence

- Child develops confidence in skills

- Leads to the virtue of Competence

Unhealthy Resolution

- Repeated failure or criticism leads to inferiority

- Child feels “not good enough”

Adult Impact:

Workplace insecurity, impostor syndrome, fear of failure.

Stage 5: Identity vs. Role Confusion (Adolescence | 12–18 years)

Central Question: Who am I?

This is one of the most critical stages. Adolescents explore beliefs, career goals, sexuality, and values.

Healthy Resolution

- Exploration leads to stable identity

- Sense of self is coherent

- Leads to the virtue of Fidelity

Unhealthy Resolution

- Pressure or lack of exploration causes confusion

- Identity diffusion or dependence on others’ expectations

Adult Impact:

Unstable relationships, career confusion, chronic self-doubt.

Stage 6: Intimacy vs. Isolation (Young Adulthood | 18–40 years)

Central Question: Can I form deep relationships?

The focus shifts from identity to emotional closeness—romantic partnerships, friendships, commitment.

Healthy Resolution

- Ability to form secure, reciprocal relationships

- Leads to the virtue of Love

Unhealthy Resolution

- Fear of closeness or emotional withdrawal

- Loneliness and isolation

Clinical Insight:

Many relationship issues stem from unresolved identity or trust crises from earlier stages.

Stage 7: Generativity vs. Stagnation (Middle Adulthood | 40–65 years)

Central Question: Am I contributing to the world?

Generativity involves nurturing others—children, students, communities, or meaningful work.

Healthy Resolution

- Sense of productivity and contribution

- Leads to the virtue of Care

Unhealthy Resolution

- Feeling stuck, unproductive, or self-absorbed

- Emotional emptiness or midlife crisis

Adult Impact:

Burnout, dissatisfaction, lack of purpose.

Stage 8: Integrity vs. Despair (Late Adulthood | 65+ years)

Central Question: Was my life meaningful?

In old age, individuals reflect on life achievements, regrets, and mortality.

Healthy Resolution

- Acceptance of life as meaningful

- Sense of peace and fulfillment

- Leads to the virtue of Wisdom

Unhealthy Resolution

- Regret, bitterness, fear of death

- Feelings of despair and hopelessness

Why Erikson’s Theory Still Matters Today

Erik Erikson designed his psychosocial model not only as a theory of development, but as a practical framework for understanding human suffering, resilience, and growth. Because it links emotional difficulties to developmental experiences, Erikson’s model is widely used across multiple mental health and helping professions.

Below is an expanded explanation of how and why Erikson’s model is applied in these fields, and how unresolved psychosocial crises often appear in adult psychological struggles.

- Psychotherapy and Counseling

In psychotherapy, Erikson’s model helps clinicians understand where emotional development may have stalled.

Therapists often use the stages to:

- Identify core emotional wounds (e.g., mistrust, shame, identity confusion)

- Understand recurring relationship patterns

- Explore early caregiving experiences without blame

- Frame problems developmentally rather than pathologically

Clinical Examples

- Chronic fear of abandonment → unresolved Trust vs. Mistrust

- Excessive self-criticism → unresolved Autonomy vs. Shame

- Lack of direction or emptiness → unresolved Identity vs. Role Confusion

Using Erikson’s framework allows therapy to focus on repairing developmental needs, not just reducing symptoms. This aligns well with psychodynamic, attachment-based, and integrative therapeutic approaches.

- Child Development and Parenting Guidance

In child psychology and parenting education, Erikson’s stages offer clear age-appropriate emotional tasks.

Professionals use the model to:

- Help parents understand normal developmental behaviors

- Prevent over-control or excessive criticism

- Encourage autonomy, initiative, and competence

- Reduce shame-based parenting practices

Practical Parenting Insights

- Toddlers need choices to develop autonomy

- Preschoolers need encouragement, not punishment, for curiosity

- School-age children need recognition of effort, not comparison

By aligning parenting strategies with psychosocial stages, caregivers can support emotionally secure and confident children, reducing the risk of later mental health difficulties.

- Career Counseling and Vocational Guidance

Erikson’s theory is highly relevant in career counseling, especially during adolescence, early adulthood, and midlife.

Career counselors apply the model to:

- Understand identity struggles behind career indecision

- Address fear of failure rooted in inferiority

- Support career transitions and midlife re-evaluation

- Help clients connect work with meaning and contribution

Developmental Lens in Career Issues

- Frequent job changes → identity confusion

- Fear of leadership roles → unresolved inferiority

- Midlife burnout → stagnation vs. generativity conflict

Rather than pushing quick career choices, Erikson’s model encourages identity exploration and value clarification, leading to more sustainable career paths.

- Geriatric Mental Health

In geriatric psychology, Erikson’s final stage—Integrity vs. Despair—is central to emotional well-being in later life.

Mental health professionals use this stage to:

- Support life review and meaning-making

- Address regret, grief, and fear of death

- Reduce depression and existential distress

- Promote acceptance and wisdom

Therapeutic Applications

- Reminiscence therapy

- Narrative therapy

- Meaning-centered interventions

Helping older adults integrate life experiences—both successes and failures—supports emotional peace and dignity in aging.

- Trauma-Informed Care

Trauma often disrupts psychosocial development by interfering with safety, trust, autonomy, and identity. Erikson’s model is therefore especially valuable in trauma-informed care.

Practitioners use it to:

- Understand trauma as developmental interruption

- Avoid blaming clients for survival adaptations

- Create corrective emotional experiences

- Restore a sense of control, connection, and meaning

Trauma and Development

- Childhood abuse → mistrust and shame

- Chronic neglect → emotional numbness

- Complex trauma → fragmented identity

Erikson’s framework helps clinicians meet clients at the developmental level where trauma occurred, rather than focusing only on adult symptoms.

Understanding Adult Psychological Struggles Through Erikson’s Lens

Many adult difficulties are not random—they are developmental echoes:

- Relationship difficulties often reflect unresolved trust or intimacy conflicts

- Low self-worth frequently stems from shame or inferiority

- Emotional numbness can be a defense developed during earlier unmet emotional needs

By identifying which psychosocial crisis remains unresolved, therapy can move from “What’s wrong with me?” to “What developmental need was unmet?”

Why This Model Remains Clinically Powerful

Erikson’s theory is still widely used because it:

- Humanizes psychological distress

- Normalizes struggle as part of development

- Integrates well with modern therapeutic approaches

- Offers hope that healing is possible at any stage of life

Clinical and Counseling Applications

As a counselor or mental health practitioner, Erikson’s stages help:

- Identify developmental wounds

- Understand recurring behavioral patterns

- Tailor interventions based on life stage

- Normalize clients’ struggles as developmental, not personal failures

Conclusion

Erik Erikson’s psychosocial theory offers a deeply compassionate and hopeful view of human development. At its core, it reminds us that growth does not stop at childhood or adolescence—it continues throughout the entire lifespan, shaped by relationships, reflection, and lived experience.

Growth Is Continuous, Not Fixed

Erikson rejected the idea that early life permanently determines who we become. Instead, he emphasized that development is fluid and revisable. Each stage introduces new opportunities to revisit earlier conflicts under different life conditions.

For example:

- An adult who lacked trust in childhood may learn safety through a secure relationship

- Someone who grew up with shame may rediscover autonomy through therapy or mastery experiences

- A person with identity confusion may find clarity later through career shifts, parenting, or personal loss

This perspective challenges fatalistic thinking and replaces it with psychological flexibility and hope.

Healing Is Always Possible

Unresolved psychosocial crises do not mean failure—they reflect needs that were unmet at a particular time. Erikson believed that healing occurs when individuals receive:

- Awareness – understanding the origin of emotional patterns

- Supportive relationships – corrective emotional experiences that rewrite old expectations

- Therapeutic intervention – structured spaces to process, integrate, and reframe experiences

Modern psychotherapy often recreates the conditions necessary for healthy psychosocial resolution—safety, validation, choice, and meaning.

Reworking Developmental Conflicts in Adulthood

Life naturally brings moments that reopen earlier stages:

- Intimate relationships revisit trust and autonomy

- Career transitions reawaken competence and identity

- Parenthood activates generativity and unresolved childhood experiences

- Aging invites reflection on integrity and life meaning

Rather than seeing these moments as setbacks, Erikson’s model frames them as second chances for growth.

Human Development Is About Meaning, Not Perfection

Perhaps the most profound contribution of Erikson’s theory is its emphasis on meaning-making. Development is not about completing stages flawlessly or avoiding pain—it is about:

- Integrating successes and failures

- Making sense of suffering

- Accepting limitations without despair

- Finding coherence in one’s life story

Psychological health, in this sense, is the ability to say:

“My life was imperfect, but it was meaningful.”

A Lifespan Perspective for Mental Health

Erikson’s theory aligns closely with contemporary mental health practices that value:

- Narrative identity

- Self-compassion

- Trauma-informed care

- Lifelong learning and adaptation

It invites both clinicians and individuals to ask not “What went wrong?” but “What is still trying to grow?”

In essence:

Erikson’s psychosocial theory reminds us that healing is not about erasing the past, but about understanding it, integrating it, and growing beyond it. At every stage of life, humans retain the capacity to develop new strengths, deeper connections, and richer meaning.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ): Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory

1. Who proposed the psychosocial theory of development?

Erikson’s psychosocial theory was proposed by Erik Erikson, a German-American developmental psychologist. He expanded earlier psychoanalytic ideas by emphasizing the role of social relationships and culture in shaping personality across the entire lifespan.

2. How many stages are there in Erikson’s psychosocial theory?

Erikson proposed eight psychosocial stages, spanning from infancy to late adulthood. Each stage involves a central psychological conflict that must be negotiated for healthy emotional development.

3. What is meant by a “psychosocial crisis”?

A psychosocial crisis refers to a developmental conflict between two opposing tendencies (for example, trust vs. mistrust or intimacy vs. isolation). These crises are not disasters; they are normal psychological challenges that promote growth when addressed constructively.

4. What happens if a psychosocial stage is not resolved properly?

If a stage is not resolved in a healthy way, it may lead to:

However, Erikson emphasized that unresolved stages are not permanent failures. They can be revisited and healed later in life through insight, supportive relationships, and therapy.

5. Can adults revisit and resolve earlier psychosocial stages?

Yes. One of the most important aspects of Erikson’s theory is that development is lifelong. Adults often revisit earlier stages during:

-

Romantic relationships

-

Career transitions

-

Parenthood

-

Therapy

-

Major life crises

These moments provide opportunities for corrective emotional experiences and psychological healing.

6. How is Erikson’s theory used in psychotherapy and counseling?

Therapists use Erikson’s framework to:

-

Identify developmental roots of emotional struggles

-

Understand recurring relationship patterns

-

Normalize clients’ difficulties as developmental, not pathological

-

Guide therapeutic goals such as rebuilding trust, autonomy, or identity

It is especially useful in psychodynamic, attachment-based, and trauma-informed approaches.

7. Why is Erikson’s theory important for parenting?

Erikson’s stages help parents understand age-appropriate emotional needs, such as:

This understanding reduces harmful practices like overcontrol, excessive criticism, or unrealistic expectations.

8. How does Erikson’s theory explain identity confusion in adolescents?

During adolescence, individuals face the crisis of Identity vs. Role Confusion. Without adequate exploration and social support, adolescents may struggle with:

-

Self-doubt

-

Peer pressure

-

Career indecision

-

Unstable self-image

Healthy identity formation requires time, experimentation, and acceptance.

9. Is Erikson’s theory relevant in old age?

Yes. The final stage, Integrity vs. Despair, is central to geriatric mental health. It focuses on:

-

Life review

-

Acceptance of one’s life story

-

Coping with regret and mortality

-

Developing wisdom and emotional peace

This stage is especially relevant in counseling older adults.

10. What is the main message of Erikson’s psychosocial theory?

The core message is that human development is about meaning, not perfection. Growth continues throughout life, and healing is always possible. Psychological struggles often reflect unfinished developmental work, not personal weakness.

Reference