Anger is one of the most misunderstood emotions. It is often labeled as negative, dangerous, or destructive, yet anger itself is not the problem. Unregulated, suppressed, or explosive anger is what creates harm—to relationships, physical health, and mental well-being.

Anger management is not about controlling or eliminating anger. It is about understanding what anger is communicating, regulating the body’s response, and expressing emotions in healthy, constructive ways.

This article explores anger management in depth—covering the psychology of anger, its causes, types, consequences, and evidence-based strategies to manage it effectively.

What Is Anger?

Anger is a natural emotional response to perceived threat, injustice, frustration, or boundary violation. From an evolutionary perspective, anger helped humans survive by preparing the body to respond to danger.

When anger arises:

-

Heart rate increases

-

Muscles tense

-

Stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol are released

-

The brain shifts into a survival-oriented mode

This response is automatic. The problem arises when anger becomes chronic, overwhelming, or poorly expressed.

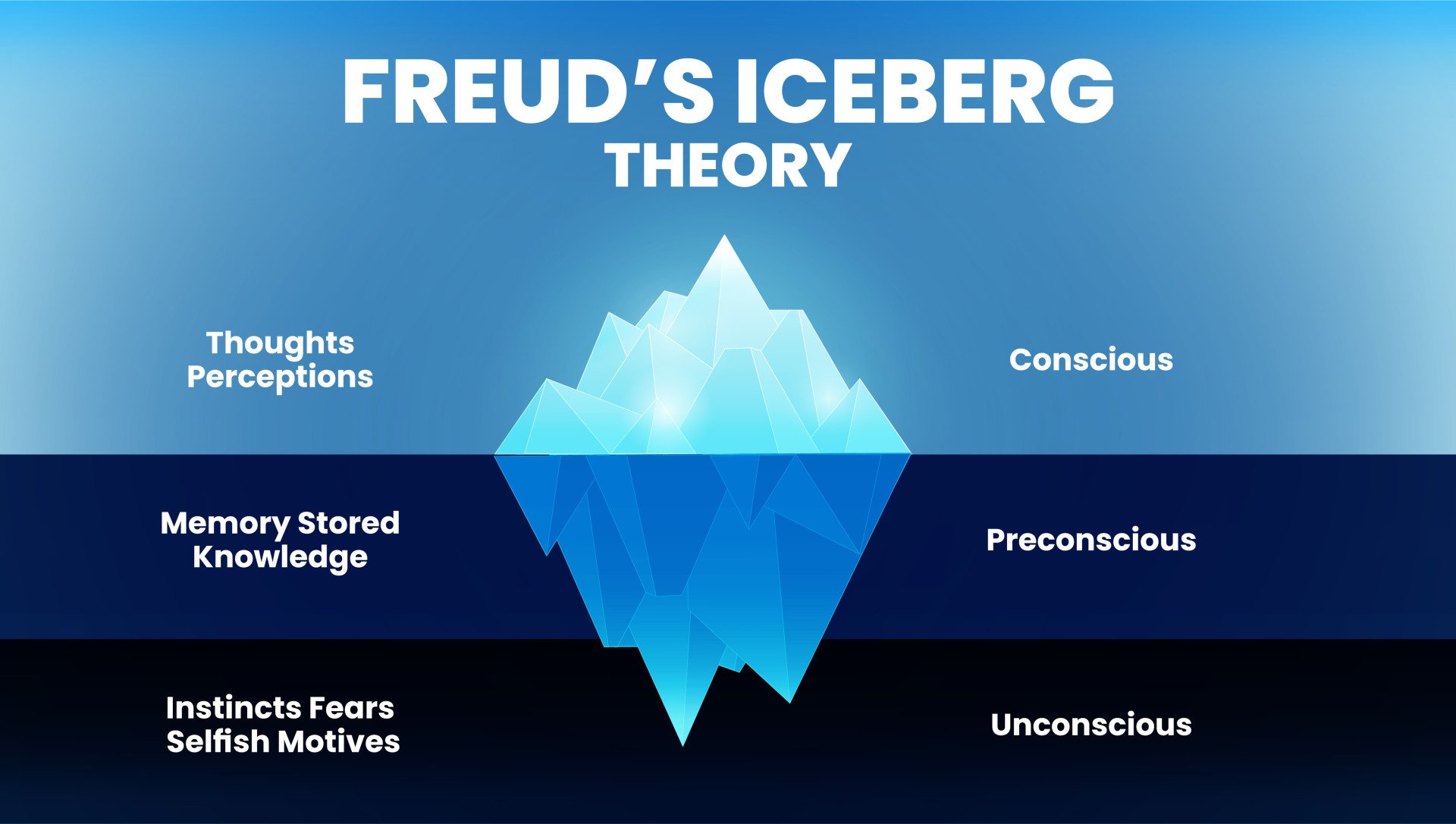

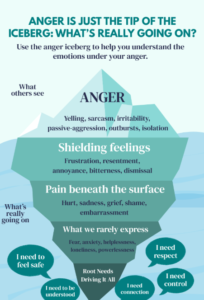

The Anger Iceberg: What Lies Beneath Anger

Psychologically, anger is often a secondary emotion. This means it sits on the surface, protecting more vulnerable feelings underneath.

Common emotions beneath anger include:

-

Hurt

-

Fear

-

Shame

-

Rejection

-

Helplessness

-

Loneliness

For many individuals—especially those taught to suppress vulnerability—anger becomes the only acceptable emotion. Understanding what lies beneath anger is a key step in managing it.

Common Causes of Anger

Anger does not emerge randomly. It usually develops from a combination of internal and external factors.

1. Unmet Emotional Needs

Feeling unheard, unappreciated, disrespected, or ignored can build resentment over time.

2. Stress and Burnout

Chronic stress lowers emotional tolerance, making even small triggers feel overwhelming.

3. Trauma and Past Experiences

Individuals with childhood abuse, neglect, or emotional invalidation may have a heightened anger response due to a sensitized nervous system.

4. Poor Emotional Regulation Skills

Many people were never taught how to recognize, name, or express emotions safely.

5. Cognitive Distortions

Rigid beliefs such as “People must respect me” or “This should not happen” intensify anger reactions.

Types of Anger Expression

Anger can manifest in different ways, each with its own psychological cost.

1. Explosive Anger

-

Yelling, aggression, verbal or physical outbursts

-

Often followed by guilt or shame

-

Damages relationships and trust

2. Suppressed Anger

-

Avoidance, emotional shutdown, people-pleasing

-

May lead to anxiety, depression, psychosomatic symptoms

3. Passive-Aggressive Anger

-

Sarcasm, silent treatment, indirect hostility

-

Creates confusion and unresolved conflict

4. Chronic Irritability

-

Constant frustration, impatience, bitterness

-

Often linked to burnout or unresolved trauma

Healthy anger management aims to replace these patterns with assertive and regulated expression.

The Impact of Unmanaged Anger

When anger is not addressed, it can affect multiple areas of life:

Mental Health

-

Anxiety disorders

-

Depression

-

Emotional numbness

-

Substance use

Physical Health

-

High blood pressure

-

Headaches

-

Digestive issues

-

Increased risk of heart disease

Relationships

-

Frequent conflicts

-

Emotional distance

-

Fear and lack of safety

-

Breakdown of trust

Anger that is ignored does not disappear—it often turns inward or spills outward.

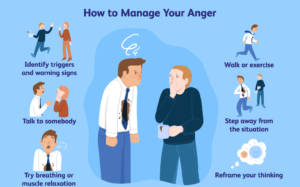

Anger Management:

-

Awareness – recognizing anger early

-

Regulation – calming the body and nervous system

-

Expression – communicating needs safely and clearly

It is a skill set, not a personality trait.

Practical Anger Management Techniques

1. Recognize Early Warning Signs

Anger gives signals before it explodes:

-

Tight jaw or fists

-

Rapid breathing

-

Racing thoughts

-

Feeling “heated” or restless

Early awareness allows intervention before escalation.

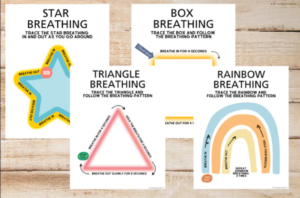

2. Regulate the Body First

You cannot reason with an overactivated nervous system.

Helpful techniques:

-

Slow diaphragmatic breathing

-

Grounding exercises (5–4–3–2–1 method)

-

Physical movement (walking, stretching)

Regulation brings the brain back online.

3. Identify the Real Emotion

Ask yourself:

-

What am I really feeling right now?

-

What need feels threatened or unmet?

Naming emotions reduces their intensity.

4. Challenge Angry Thought Patterns

Cognitive reframing helps reduce emotional intensity:

-

Replace “They are disrespecting me” with “I feel ignored, and that hurts”

-

Replace “This always happens” with “This situation is difficult, not permanent”

5. Learn Assertive Communication

Healthy anger expression sounds like:

-

“I felt upset when…”

-

“I need…”

-

“This boundary is important to me”

Assertiveness respects both self and others.

6. Release Anger Safely

Anger needs an outlet—not destruction.

Healthy outlets include:

-

Journaling

-

Exercise

-

Creative expression

-

Talking with a trusted person

Anger, Masculinity, and Social Conditioning

Many men are socialized to:

-

Avoid vulnerability

-

Suppress sadness or fear

-

Use anger as the only emotional outlet

This makes anger management especially important in men’s mental health. Learning emotional language and regulation is not weakness—it is emotional maturity.

When to Seek Professional Help

Anger management therapy may be helpful if:

- Anger feels uncontrollable

- It begins to harm personal and professional relationships.

- It increases the risk of aggressive or violent behavior.

- It occurs alongside trauma-related symptoms, anxiety, or depressive disorders.

Therapy helps uncover underlying causes and builds long-term emotional regulation skills.

Final Reflection

Anger is not the enemy—it is a messenger. It points to boundaries, unmet needs, pain, and injustice. When understood and regulated, anger can become a source of clarity, self-respect, and change.

True anger management is not about suppressing emotion—it is about learning to listen, regulate, and respond rather than react.

Written by Baishakhi Das

Counselor | Mental Health Practitioner

Qualifications: B.Sc in Psychology | M.Sc | PG Diploma in Counseling

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ): Anger Management

1. Is anger a bad emotion?

No. Anger itself is a normal and healthy emotion. It signals that something feels unfair, threatening, or emotionally painful. Problems arise when anger is suppressed, misdirected, or expressed aggressively.

2. What is the difference between anger and aggression?

Anger is an emotion, while aggression is a behavior. You can feel angry without being aggressive. Anger management focuses on regulating the emotion so it can be expressed assertively rather than destructively.

3. Why do some people get angry more easily than others?

Anger sensitivity can be influenced by:

-

Childhood experiences and emotional modeling

-

Chronic stress or burnout

-

Trauma or unresolved emotional wounds

-

Poor emotional regulation skills

-

Rigid thinking patterns

People who grew up in invalidating or unsafe environments often have a lower emotional tolerance for frustration.

4. Is anger always caused by the present situation?

Often, no. Many anger reactions are triggered by old emotional wounds. The current situation may resemble earlier experiences of rejection, disrespect, or powerlessness, activating a stronger response than the present moment alone would justify.

5. What are the physical signs that anger is building up?

Common early signs include:

-

Tight jaw or clenched fists

-

Rapid heartbeat

-

Shallow or fast breathing

-

Feeling hot or restless

-

Racing or rigid thoughts

Recognizing these signs early is key to effective anger management.

6. Can suppressed anger cause health problems?

Yes. Chronic suppression of anger has been linked to:

-

Anxiety and depression

-

Headaches and digestive problems

-

High blood pressure

-

Emotional numbness

-

Passive-aggressive behavior

Anger that is not expressed safely often turns inward.

7. Are anger management techniques effective?

Yes—when practiced consistently. Techniques such as breathing exercises, cognitive restructuring, emotional awareness, and assertive communication are evidence-based and widely used in psychotherapy.

8. When should someone seek professional help for anger?

Professional support is recommended if:

-

Anger feels uncontrollable

-

It harms relationships or work life

-

There is verbal or physical aggression

-

Anger is linked with trauma, anxiety, or depression

Therapy helps address both symptoms and root causes of anger.

9. Is anger management only for people who “lose control”?

No. Anger management is also for people who:

-

Suppress emotions

-

Feel chronically irritated

-

Struggle to set boundaries

-

Feel guilt or shame after expressing anger

Healthy anger expression is a life skill, not a crisis tool.

10. What is the core goal of anger management?

The goal is not to eliminate anger, but to:

-

Understand what anger is communicating

-

Regulate the body’s stress response

-

Express emotions clearly and respectfully

In short: respond instead of react.

Reference

-

American Psychological Association – Anger

https://www.apa.org/topics/anger

— Evidence-based overview of anger, its effects, and management strategies. -

National Institute of Mental Health – Stress and Emotion Regulation

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/stress

— Explains how stress impacts emotional control, including anger. -

Verywell Mind – Anger Management Techniques

https://www.verywellmind.com/anger-management-strategies-4178870

— Practical, psychology-backed anger management strategies. -

Mayo Clinic – Anger Management: Tips to Tame Your Temper

https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/adult-health/in-depth/anger-management/art-20045434

— Medical perspective on anger, health risks, and coping skills. -

Psychology Today – Understanding Anger

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/anger

— Explores emotional, cognitive, and relational aspects of anger. -

World Health Organization – Mental Health and Emotional Regulation

https://www.who.int/teams/mental-health-and-substance-use

— Global mental health framework relevant to emotional regulation. -

National Health Service (UK) – Anger Management

https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/conditions/anger-management/

— Public mental health guidance on managing anger safely. - 7 Signs You Need to Talk to a Therapist — Don’t Ignore These

Introduction

Introduction